'That’s assault mate’: Investigation into alleged misconduct in a private prison and how it was handled

Date posted:

Summary

[I said] ‘That’s assault, mate. That’s assault’. … He just looked at me and went, ‘I don’t know what assault you’re talking about’.

Kyle to the Supervisor

What we investigated

We received complaints alleging that private prison staff assaulted a man being held on remand (‘Kyle’), restricted his access to medical help, and encouraged a further assault on him by other people in the prison.

The events were alleged to have unfolded at Ravenhall Correctional Centre (‘Ravenhall’), a private prison run for the State by The GEO Group Australia Pty Ltd (‘GEO’).

We investigated whether a Supervisor and an Officer at Ravenhall used unreasonable force on Kyle, and failed to report it. We also looked at whether the Supervisor disabled a communication device in Kyle’s cell, and later sent three men there to harm him.

As part of this we considered GEO’s review of the alleged events and whether the actions it took in response were adequate. We also investigated how Corrections Victoria, which is part of the Department of Justice and Community Safety (‘the Department’), oversaw the matter.

Why it matters

The allegations raised serious concerns spanning multiple corruption risks: excessive use of force, blurred professional boundaries, misuse of power and inhumane treatment of a person in prison.

Days before the alleged assaults on Kyle, Corrections Victoria had finalised a new strategy to improve its scrutiny of private prisons amid ongoing concerns about operator performance.

Kyle’s case was an important test of these enhanced efforts to ensure private prison operators are delivering a vital public function to expected standards.

It is essential that the various internal and external oversight mechanisms built into the private prison contracts work properly to ensure full accountability, to safeguard the safety and rights of people in prison, and to maintain trust in the corrections system.

What we found

In relation to the allegations about the Supervisor and the Officer:

- The Supervisor used unreasonable force, and both he and the Officer failed to report this. Though both staff members and GEO deny any force was used, on the balance of probabilities we found the Supervisor struck Kyle in the face and the Officer did not intervene to protect Kyle. We also found neither officer adhered to incident reporting rules.

- The Supervisor restricted Kyle’s access to medical help after punching him. Soon after Kyle left the Supervisor’s office where the punch happened, the Supervisor disabled Kyle’s InCell device. This prevented Kyle from using it to make a medical appointment. We did not accept the multiple reasons the Supervisor gave for turning off the device.

- The Supervisor did not send three people to Kyle’s cell to further harm him. We were not satisfied to the required standard of proof that the Supervisor influenced three people in prison to assault Kyle. However, he referred to the men as ‘heavies’ who kept the unit ‘in check’, and he did direct at least one of them to visit Kyle’s cell. While we do not know exactly what happened inside, Kyle expressed fear for his life immediately after.

In relation to how GEO and Corrections Victoria handled the assaults and other concerns arising from the alleged events:

- Separate investigations by Corrections Victoria and GEO into the events reached different findings. Corrections Victoria found the Supervisor did assault Kyle, which was a service delivery breach under the contract. GEO was unable to substantiate an assault. This exposed a misalignment in their respective approaches to reviewing incidents and performance.

- GEO was too blinkered to some of the broader integrity concerns the case raised. This highlights some potential pitfalls of self-scrutiny by private prisons, and underscores the importance of Corrections Victoria providing an effective layer of external oversight.

- The Supervisor stayed on frontline duties for weeks after the allegations surfaced and resigned without facing disciplinary action. This raises questions about how to balance GEO’s right as a private company to manage its own workforce against the responsibilities the company and the State have for people held at Ravenhall.

- GEO paid a significant financial penalty because the assault was a service delivery breach under the Ravenhall contract. Corrections Victoria now acknowledges the matter should also have been treated as a ‘Probity Event’ under the contract. GEO and Corrections Victoria have since jointly developed a ‘probity framework’ to improve incident handling.

- The InCell system still allows staff to arbitrarily restrict access. GEO told us it had clarified its policy and reminded staff InCell access was to be changed only in limited circumstances and in keeping with the Human Rights Charter. The Department told us it was satisfied with this, and that it had changed a relevant Commissioner’s Requirement. However, we think further system controls are required.

Responses to our findings

- The Supervisor has always denied using any force against Kyle and insisted there was no incident to report. He said he had legitimate reasons to disable Kyle’s InCell device. He strongly disagreed with our findings and said he had not acted contrary to the Commissioner’s Requirements, Corrections Act or Human Rights Charter.

- The Officer has always denied that he witnessed any use of force or that he failed to intervene to protect Kyle, and maintained there was no incident to report. He strongly disagreed with our findings.

- The GEO Investigator rejected our conclusion that the Supervisor assaulted Kyle, and stood firmly by GEO’s investigation process, report and findings. He maintained there were too many variables to find that an assault occurred, including ‘significant’ differences in the accounts key witnesses gave.

- GEO asked us to publish its detailed response to our report in full. You can read it in Appendix 2 (with minor redactions). GEO noted the company’s silence on some topics raised in our report ‘should not be taken as agreement’ with our findings.

- Corrections Victoria emphasised it works with GEO constructively to manage any service delivery issues, and that it has a detailed assurance framework in place to proactively monitor private prison performance and ensure the safety and humane treatment of people in prison.

What needs to change

Overall, we are concerned at the potential for integrity risks and other deficiencies to slip through both GEO’s internal controls and the Department’s external oversight. We have made five recommendations intended to ensure people in prison are not deprived of access to medical treatment and to strengthen oversight of serious incidents in private prisons.

Background

Why we investigated

On 10 October 2022 the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (‘IBAC’) referred a public interest complaint to us for investigation.

The complaint alleged two staff at Ravenhall Correctional Centre (‘Ravenhall’) had assaulted a person being held on remand – who we will refer to as ‘Kyle’. It also alleged staff influenced three other people held in the prison to further assault him.

Following a mandatory report by the Department of Justice and Community Safety (‘the Department’), on 10 November 2022, IBAC referred a second public interest complaint to us about the same matter which included some extra details.

What we investigated

The allegations in the two complaints referred by IBAC were worded slightly differently. Our initial enquiries also revealed one of the named officers was incorrectly identified, and this required correction.

Taking this into account, on 4 May 2023 a former Deputy Ombudsman authorised a public interest complaint investigation under section 15C of the Ombudsman Act 1973 into four allegations.

They were that on 21 August 2022:

- a Corrections Supervisor (‘the Supervisor’) and a Corrections Officer (‘the Officer’) used unreasonable force against Kyle

- the Supervisor misused his position to restrict Kyle’s InCell communications device, limiting access to medical and other help

- the Supervisor misused his position to influence three prisoners to assault Kyle, after Kyle threatened to complain about the officers’ assault

- the Supervisor and the Officer failed to report their use of force on Kyle.

Ravenhall is a private prison, run for the State by The GEO Group Australia Pty Ltd (‘GEO’). The Supervisor and the Officer were employed by GEO at the relevant time.

As part of our investigation, we considered GEO’s own review of the matters raised, and the adequacy of its response.

We also used our ‘own motion’ powers under section 16A of the Ombudsman Act to investigate aspects of the Department’s oversight of GEO, especially by Corrections Victoria (a business unit of the Department).

How this report is organisedChapter 1 of this report considers and makes findings on the four allegations.Chapters 2 and 3 consider how GEO and Corrections Victoria responded to the alleged events, and whether these actions were adequate. |

Other investigations into the events of 21 August 2022Use of force incidents and allegations of assault by prison staff automatically trigger a range of internal and external reviews. Three other investigations have looked at the events in question:GEO considered whether the Supervisor and the Officer assaulted Kyle, and whether the Supervisor encouraged a further assault on Kyle by others. Its October 2022 investigation report was based on interviews with six Ravenhall staff, six people on remand (including Kyle), and a review of CCTV and other prison records. It found, based on the balance of probabilities, the assault allegations could not be substantiated. Corrections Victoria considered whether an assault on Kyle by staff occurred. It used different criteria to GEO Group when assessing the evidence. After reviewing CCTV footage, and interviewing Kyle and one other witness, its April 2023 final report found an assault on Kyle by staff did occur, and a financial penalty was applied. Victoria Police opened a criminal investigation in August 2022 after receiving a mandatory report from Ravenhall about the alleged assaults, but closed the case because Kyle did not want it pursued. |

Our investigation had access to the GEO and Corrections Victoria investigation reports, plus many of the documents and interview transcripts underpinning them. We refer to these throughout this report, especially where opinions differ.

Procedural fairness and privacy

Our investigation was guided by the civil standard of proof which requires that the facts be proven on ‘the balance of probabilities’. This differs from the criminal standard of ‘beyond reasonable doubt’.

To reach our conclusions, we considered:

- the nature and seriousness of the allegations made, and matters examined

- the quality of the evidence

- the gravity of the consequences an adverse opinion could create.

This report makes adverse comments, or includes comments which could be considered adverse, about the following parties:

- the Supervisor

- the Officer

- Kyle

- Adam

- the Induction Billet

- the Meal Billet

- the Former Laundry Billet

- the ‘fourth man’ in Kyle’s cell

- the GEO Investigator

- GEO

- the Department.

In line with section 25A(2) of the Ombudsman Act, we provided these parties with a reasonable opportunity to respond to a draft extract of this report. This final report fairly sets out their responses.

In line with section 25A(3) of the Ombudsman Act, we make no adverse comments about anyone else who can be identified from the information in this report. Where a person is named or can be identified this is because:

it is necessary or desirable to do so in the public interest

identifying them will not cause unreasonable damage to their reputation, safety or wellbeing.

Individuals in this report, including Kyle, are de-identified to protect their privacy, safety and reputation.

Context

The Victorian prison system

Across Victoria, there are 11 public prisons run by the Department and, at the time of writing, three private prisons run under contract to the Department. The privately operated Port Phillip Prison is set to close at the end of 2025.

Corrections Victoria is responsible for prison management in Victoria, including administering the private prison contracts. It is led by a Commissioner.

All Victorian prisons, public and private, must adhere to the Corrections Act 1986 and the accompanying Corrections Regulations 2019.

They are all also subject to requirements and standards set by Corrections Victoria including:

- a set of Commissioner’s Requirements spelling out high-level details for operational matters to ensure consistency across prisons

- a set of Correctional Management Standards guiding the outcomes and outputs to be achieved by prison operators.

All private prisons have their own local procedures for officers to follow, known as ‘Operating Instructions’. These guide how the Commissioner’s Requirements are implemented.

All prisons must also act in line with the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (‘the Human Rights Charter’) which specifies the human rights afforded to all Victorians. Sections 10 and 22 are particularly relevant to the prison context. They state:

- a person must not be treated or punished in a cruel, inhuman or degrading way

- a person deprived of liberty must be treated with humanity and with respect for their inherent human dignity.

Use of force in prisons

At times it can be both necessary and lawful for officers to use force on people in prison. However, given the obvious power imbalances, this is tightly regulated by laws, policies and procedures.

The law allows a prison officer to use force against a person in prison if:

- they have a lawful reason

- the force used is not unreasonable in terms of the level or type of force and the length of time it is applied

- the use of force is consistent with the Human Rights Charter.

The use of force in prisons is guided by the Commissioner’s Requirements, which reflect relevant provisions in the Corrections Act and the Crimes Act 1958.

Commissioner’s Requirement 1.1.1 Use Of Force (May 2021) states that ‘reasonable force’ may be lawfully used by prison officers on people in prison to:

- compel them to comply with a lawful order

- prevent them from escaping custody

- prevent a crime or arrest someone believed to have committed one

- prevent them from assaulting another person or being assaulted

- prevent suicide.

Commissioner’s Requirement 1.1.1 also states physical intervention must only be used as a last resort, and that officers should first try to resolve situations using communication skills.

This is underpinned by Ravenhall’s Operating Instruction 3.7.1 Use Of Force (November 2020), which states its guiding philosophy as:

Reasonable force shall only be used in accordance with the law, where a situation cannot be resolved by other means, and then only for the minimum time needed to reach resolution.

Ombudsman’s June 2022 report on use of force in two public prisonsTwo months before the alleged incidents involving Kyle, we published a Report on investigations into the use of force at the Metropolitan Remand Centre and the Melbourne Assessment Prison (‘June 2022 use of force report’). The report examined eight cases, and found unreasonable force was used in four. All eight showed concerning behaviour and poor decision making by officers, and suggested systemic problems. The report made 12 recommendations including requiring officers to use monitored areas for sensitive conversations, ensuring prisons actively monitor and address officer conduct issues, and improving public reporting to build a culture of transparency. The Department fully or partially accepted 11 of these. As at February 2025, one recommendation had been fully implemented, two were partially implemented, and eight were in progress. |

Ravenhall prison

Ravenhall is one of two private prisons GEO runs on behalf of the State. Opened in 2017, the medium-security men’s facility in Melbourne’s west is Victoria’s largest prison. It can accommodate 1,300 people.

Corrections Victoria’s website notes that Ravenhall’s areas of focus include:

- new approaches to reducing the risk of offending

- integrated and holistic mental health support

- targeted approaches for people in prison with challenging behaviours.

Those in custody at Ravenhall are a mix of people convicted and sentenced, and people being held on remand before or during their criminal proceedings. In June 2022, half of the people in Ravenhall were unsentenced.

The unit Kyle was in is for people on remand. The guiding principle of Commissioner’s Requirement 2.3.8 Remand Prisoners (September 2020) is that because people on remand are unsentenced, they generally face fewer restrictions than people who have been convicted. This includes increased access to telephone calls for legal advice.

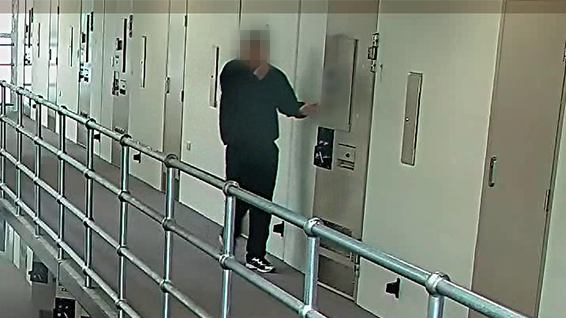

CCTV cameras capture footage across much of Ravenhall, though there are some blind spots including the Supervisor’s office, a secure staff area, and inside cells. The CCTV does not record audio.

Along with an intercom to contact officers, cells at Ravenhall are equipped with an ‘InCell’ communications device. InCell enables users to access a variety of services, and to make a complaint, submit a medical request, or message prison staff.

The Ravenhall contract

The Ravenhall Prison Project Agreement (‘Ravenhall contract’) is a contract between the State of Victoria and ASGIP III Ravenhall Project Pty Ltd to build and run the prison until 2042.

GEO is subcontracted to manage and operate the prison.

Various oversight mechanisms are built into the contract to enable the State to monitor GEO’s performance against expected standards.

GEO has an internal investigation function known as the Office of Professional Integrity (‘OPI’). It is led by the OPI Manager, who we refer to in this report as the ‘GEO Investigator’.

The Ravenhall contract specifies 20 service delivery outcomes (‘SDOs’) and 25 key performance indicators (‘KPIs’). GEO is required to regularly report on these to Corrections Victoria.

GEO receives a quarterly ‘service linked fee’ if it successfully meets agreed SDO and KPI thresholds. This payment can be reduced if GEO fails to meet expected standards.

Other financial penalties can also be applied for specific ‘charge events’ such as escapes, some deaths in custody and professional misconduct.

Public reporting about Ravenhall’s contract and performance

The Ravenhall contract is available to view on the ‘Buying for Victoria’ website. However, some parts are redacted for commercial or security reasons. This includes details of the SDOs and KPIs.

We obtained an unredacted copy of the contract under summons to help us understand GEO’s obligations, along with copies of Corrections Victoria documents about Ravenhall’s performance.

Our discussion in this report of material not already in the public domain was informed by commercial and security considerations.

Chapter 1: The alleged events of 21 August 2022

This chapter examines in detail each of the four allegations we investigated.

Figure 1: Central figures in the events we investigated

| Kyle: on remand at Ravenhall as he waited for a court hearing. This was his first time in prison. He had spent time in the medical unit for poor mental health. The Supervisor: alleged to have punched Kyle in the face during an incident in his office, and to have influenced three people to further assault Kyle. The Supervisor denies both allegations. Was acting in the role at the time. The Officer: alleged to have shoved Kyle into a chair during the incident in the Supervisor’s office. Denies using or witnessing any force against Kyle. Trio held on remand in the same unit as Kyle: commonly moved around the unit as a group. Alleged to have assaulted Kyle at the urging of the Supervisor, which they all deny. Described by the Supervisor as ‘heavies’ who helped keep the unit ‘in check’. Adam: a person on remand in the same unit as Kyle. He spent time with Kyle on 21 August. |

Source: Victorian Ombudsman

Figure 2: Summary timeline of key events

Sunday 21 August 2022

9.44am Kyle phones his father. They discuss his pending charges and the possibility one could result in a lengthy jail term. At the end of the call Kyle returns to his cell.

———

10.01am Kyle, who experienced poor mental health on arrival at Ravenhall, feels depressed and anxious about his pending charges after speaking with his father. He goes to the officers’ post and demands a call to his lawyer. The request is denied.

———

10.01am Kyle swears at an officer and angrily returns to his cell. The Supervisor told us a group of onlookers heckled and called out ‘bad dog’ as Kyle passed them, a signal Kyle could be in danger from other people held in the prison.

———

10.04am After Kyle ignores an intercom call from the Supervisor, two officers come to his cell and direct him downstairs to the Supervisor’s office.

———

10.05am Kyle enters the office and shuts the door. The Supervisor and the Officer are inside. Kyle alleges he is punched in the face by the Supervisor and pushed into a chair by both officers. They deny using any violence. They say Kyle was upset and they discussed his mental health and unit rules.

———

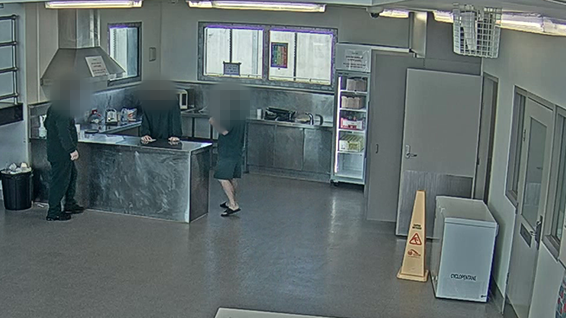

10.09am People, including Adam, linger in a kitchen near the office as Kyle is inside speaking with his lawyer from the Supervisor’s phone. The officers say they allowed a call to ease Kyle’s anxiety. He says he did not mention the alleged assault during the call because the officers were beside him.

———

10.11.29am Kyle exits the office. No injuries are visible on the CCTV. Kyle says he stopped some bleeding with tissues given to him by the officers before stepping out. The officers say they gave Kyle tissues to dry his tears because he had been crying hysterically.

———

10.11.43am Kyle holds the back of his right hand to the left side of his face as he heads back upstairs. He told us once back in his cell, he tried to seek medical help but was unable to because the Supervisor had cut access to the InCell device normally used to lodge requests.

———

10.11.48am Adam follows Kyle into his cell and stays about a minute. Adam later told us and Corrections Victoria, though not GEO, that he saw injuries to Kyle’s lip and eye that were not there before Kyle’s visit to the Supervisor’s office.

———

10.21am Other people have been coming and going from Kyle’s cell. CCTV captures shadows on the door suggesting a burst of activity inside. This could potentially be an assault, or a recreation of one. Kyle told us he was just talking with people.

———

10.39am The Supervisor briefly looks into Kyle’s cell on his way past to unlock another cell. He told us he wanted to check on Kyle because he had seen multiple people going in and out. He said Kyle ‘appeared fine’.

———

10.43am One of many people to visit Kyle’s cell in the hour after the first alleged assault is the unit’s peer listener. He told GEO that Kyle looked like he had been crying and had a swollen lip but had not said how the injury occurred. The peer listener brought Kyle an ice pack.

———

11.11.43am Kyle decides to visit the Supervisor’s office again. He holds the left side of his face as he heads downstairs.

———

11.11.56am The clearest available shot of Kyle’s face shows no visible injury as he waits to see the Supervisor. However, CCTV captures him exploring his lip and inside his mouth with his hand and tongue as if in pain.

———

11.13am Kyle spends two minutes alone with the Supervisor in the office. Kyle told us, but not GEO, that he’d been egged on by others to ask for nicotine patches in exchange for not reporting the alleged officer assault. The Supervisor maintains no assault happened. He agrees Kyle asked for patches, which he refused.

———

11.18am After leaving the Supervisor’s office Kyle spends time in Adam’s cell. Adam told GEO, but not us, that they talked about how Kyle owed ‘about 30 bucks’ to someone, perhaps for canteen items or drugs.

———

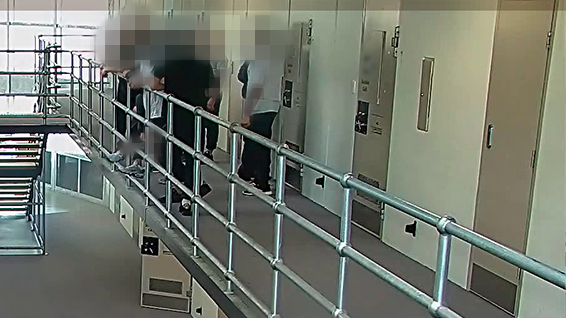

11.24am The trio head into the office, though the Supervisor says he only spoke to one – the ‘Induction Billet’ whose job it is to show new arrivals the ropes. The Supervisor told GEO he didn’t know why the men were ‘always together’. He described them as ‘heavies’ who helped keep the unit ‘in check’.

———

11.25am The trio of men exit the Supervisor’s office and go straight to Kyle’s cell. Most of the other people in the cell exit. The door closes leaving five people inside – Kyle, the trio and one other.

———

11.27am Four men exit the cell. Kyle alleges the trio assaulted and threatened him. He told GEO they told him to show officers respect and not to ‘rat’ on anyone. The trio told GEO they did not harm Kyle, though gave inconsistent accounts of what happened inside the cell.

———

11.31am Alone inside his cell as a group of people who had gathered outside disperses, Kyle makes an intercom call to officers, stating: ‘I’m fearing for my life, I want out’.

———

11.32am Two officers – including the Officer alleged to have pushed Kyle in the office incident – leave their post to go and check on Kyle. One notes him rambling, ‘almost like he was having a breakdown or an anxiety episode’. They tell him to put a lock on and call for help if necessary.

———

[No image available inside cell]

12.28am As people flood toward the kitchen for lunch, Kyle is alone in his cell. He makes another intercom call for help: ‘Yo, can I ask to be moved to protection – I’m still fearing for my life’. Officers tell him to lock his door and they’ll come and speak to him.

———

12.28am As Kyle makes his intercom call, one of the trio drops off some lunch. The man then goes back downstairs to speak briefly with the Supervisor who asks him to check on Kyle’s welfare.

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on CCTV footage and documents supplied by the Department and GEO.

Allegation 1 – Unreasonable use of force by officers

The first allegation we examined centred on whether the Supervisor and the Officer used unreasonable force against Kyle.

What Kyle says happened

Before we interviewed him, Kyle had given multiple formal and informal accounts of what happened inside the Supervisor’s office on his first visit that day.

We carefully considered the various accounts Kyle gave to others and found them broadly consistent with what he told us. Some of the details did differ. We do not discuss every difference in this report, but do note inconsistencies we consider significant.

One obvious error in all of Kyle’s accounts is his physical description of the Officer. In our view, Kyle’s confusion is understandable given the circumstances.

Kyle stated he was assaulted by the Supervisor and the Officer as he stood in the office soon after entering:

… [They] said, ‘What’s wrong? What made you go off like that? Like yeah, you shouldn’t be doing that and obviously we can’t have that happen …’.

And then that’s when I said, ‘I’m bloody depressed, I’m anxious. I just want to bloody call up my lawyer, but you won’t give me a bloody call with my lawyer’. And then that’s when they’ve looked me in the eye and said, ‘Well, there’s rules you’ve got to follow. One, you can’t be swearing at us’.

And then that’s when I’ve just looked at [the Supervisor] and said, ‘Fuck your rules, I don’t care’. That’s when next minute, he stepped forward a little bit and just gone boom …

Kyle described the punch as ‘forceful’ and said it made his head snap back.

He said both men then grabbed him and pushed him to the floor, face down.

Kyle said while on the floor, he challenged the Supervisor about the assault and warned he would be reporting it:

[I said] ‘That’s assault, mate. That’s assault. Someone will hear about this’… He just looked at me and went, ‘I don’t know what assault you’re talking about’.

Kyle said the Supervisor and the Officer picked him up from the floor and shoved him into a chair. He said the Supervisor moved to the door, blocking him from leaving.

Kyle said the officers then offered him a call to his lawyer, and that he responded:

I’ll take the call, but you just assaulted me. The Ombudsman is still going to hear about this, no matter what you say or do. You just assaulted me.

One of the officers dialled Kyle’s lawyer from the office phone. Kyle said it was a brief call as the lawyer did not have much time. He did not mention the assault.

Kyle told us he did not mention what had just happened, ‘just due to being assaulted … and not knowing what would happen next’. Kyle similarly told GEO he had not said anything to the lawyer because he was ‘in fear at the time’ and ‘didn’t want another assault’.

Kyle said that after the call, the officers told him to clean himself up and gave him tissues which he used to wipe up blood and stem bleeding from his nose before returning to his cell.

Kyle alleges that later that morning he was bashed in his cell by the trio that he believes were acting on the instruction of the Supervisor. This is covered in more detail soon, under Allegation 3.

Figure 3: Kyle’s accounts over time of the incident in the office

| 10.11am Sunday 21 August 2022: The first person to talk to Kyle outside the office says Kyle told him that officers had punched him in the face and thrown him to the ground. 1.42pm: In a recorded call to his mother, Kyle says he was punched by the Supervisor for ‘being a smart arse’, and later that morning by three people in prison. 3.29pm: In a recorded call with his father, Kyle says he ‘got king hit’ and ‘slammed to the ground’ by the Supervisor and was denied medical help. 8.05am Monday 22 August 2022: Kyle tells an officer who asked about his obvious lip injury that the Supervisor punched him in the face and took him to the ground. The officer’s incident report notes that Kyle ‘advised he did not initiate nor retaliate’. 8.35am: In an interview with the duty supervisor, Kyle says he was assaulted by the Supervisor and another officer. 8.47am: Kyle tells a nurse assessing his injuries that he has been assaulted by an officer and later by three people in prison. They note Kyle’s injuries as bruising and swelling to the left lower lip, and a small cut near the left eye. 29 August 2022: Kyle tells GEO Investigator that the Supervisor ‘stepped forward and king hit’ him with a fist to the left side of his face causing his lip to bleed. He says he was also ‘slammed on the chair’ by both officers. 21 October 2022: Kyle tells Corrections Victoria that the Supervisor punched him in the face which resulted in him falling to the ground. 6 July 2023: Kyle tells us the Supervisor stepped forward and punched him to the eye and jaw. He said he was then forced to the ground, and onto a chair, and that he suffered a blood nose. |

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based supplied documents.

Kyle’s account of his injuries and the events shifted over timeWhen we asked him, Kyle recalled that the Supervisor’s strike connected with his left eye and jaw.He said this resulted in watering eyes and ‘constant blood out of the nose’. He recalled being given tissues and stuffing one up his nostril to stem the bleeding before he left the office. This differed slightly from his earlier accounts to others, which centred on a split to the inside of his lip which bled a lot. We noted this inconsistency, but also noted some time had passed and that memory is imperfect. Kyle’s account of being struck to the eye and jaw aligned with injuries observed by the nurse who examined him the next day (though we note the possibility Kyle suffered one or more other assaults after the incident in the office). The Officer’s response to our draft report said that Kyle’s accounts of the events over time differed ‘significantly’, were ‘unreliable’, and ‘lacked cogency’. He stated: For example, in some accounts Kyle alleges officers (plural) pushed him to the ground, in other accounts he does not allege he was pushed to the ground at all, in two accounts he says that it was the Supervisor who pushed him to the ground and in one account Kyle says he fell to the ground. Only three of the ten accounts contain any reference to Kyle being forced into a chair. We also noticed these inconsistencies and took them into account when making our findings. The GEO Investigator said in his response to an extract of this report that he also considered shifts in Kyle’s accounts ‘significant’. In particular he questioned why there was no tissue visible in any available footage of Kyle, and how Kyle could have confused a nosebleed and a cut in the mouth. GEO also asserted that Kyle’s accounts had shifted ‘markedly’. In Kyle’s response to our report, he stood by the central thread of his accounts – that he was struck to the face. He said in his view, it was the officers’ accounts rather than his own that did not add up. |

What the officers say happened

As was the case with Kyle, when we interviewed the Supervisor and the Officer, they had each given multiple accounts over time of the events.

At all times both have denied any force was used against Kyle.

We carefully considered the various versions of events they have given in relation to this allegation. These were broadly consistent with what they told us. The accounts of the Supervisor and the Officer were also largely consistent with each other.

The Supervisor

The first account the Supervisor recorded was on the day of the alleged assault. His entry on Kyle’s file stated:

[Kyle] approached officer’s post distressed about upcoming court date. He appeared quite upset and asked Supervisor for a welfare call to his lawyer because he can’t settle until he lets his lawyer know to drop certain charges. Supervisor facilitated welfare call for [Kyle] in office to lesson [sic] [Kyle’s] anxiety considering [Kyle’s] at risk history.

Eight days later, at the request of his manager, the Supervisor completed a written incident report. It described a ‘distressed and irritable’ Kyle demanding a call with his lawyer, and abusing officers when denied.

The Supervisor wrote that during that exchange, others in the unit had heard Kyle openly discussing his charges. This is discouraged in prison. The Supervisor wrote that onlookers heckled and called Kyle names such as ‘bad dog’ – which he took as a sign Kyle could be in danger.

The Supervisor stated that to defuse this situation with the other prisoners, and to discuss Kyle’s welfare, he called him to his office.

Once inside, he wrote, Kyle ‘started to cry hysterically in the chair’, so the Officer gave him some water and tissues. The Supervisor observed Kyle was anxious about his upcoming criminal charges and being in prison:

He began to heighten when talking about rules in prison especially regarding other prisoners. I allowed [Kyle] to vent but it appeared that he was unwell as he began talking about hearing voices.

The Supervisor wrote that the Officer dialled Kyle’s lawyer, and that Kyle spoke to her ‘for some time’ before thanking him and leaving the office, ‘still visibly upset’.

We interviewed the Supervisor almost a year after the incident. When we directly put the allegation to him that he had punched Kyle in the face, the Supervisor declined to answer ‘due to legal advice’:

I gave my side of the story, and I’m not answering that question.

The Supervisor did elaborate on his perceptions of Kyle’s behaviour on the day, and generally. He described Kyle as ‘quite unwell, mentally unwell, unstable’ and said officers were ‘constantly having issues’ with him. He said, for example, they had warned Kyle ‘over and over’ about standing naked for the morning count, and ‘spamming’ people via the InCell device.

We did not find references to these behaviours noted on Kyle’s file, or that he had been warned to stop, suggesting the Supervisor did not consider them significant enough to record. (We did note that another officer told GEO Kyle had been naked ‘a few days in a row’ so they ‘had a chat with him’. Kyle denied this. He said he had been naked in front of officers just once, when one walked in on him showering. He also denied ‘spamming’ officers.)

The Supervisor said on the day in question Kyle was ‘quite heightened’ when he entered the office – pacing, crying, and saying things like ‘I’m just going so mad’ and ‘I’m fucking hearing voices’.

The Supervisor told us he considered making a mental health referral for Kyle, but did not do so because he knew ‘psych nurses’ did not work Sundays. He also observed Kyle was not the most ‘mentally unwell’ person in the unit at that time, and said he felt nothing would probably have happened even if he had made a report, given resource constraints.

In response to our draft report, the Supervisor said he stood by the detailed account he gave to us when we interviewed him.

The Officer

The Officer was present when Kyle first approached and abused officers, and was also in the Supervisor’s office with Kyle for the follow-up discussion.

He denied personally using any force on Kyle, and when we asked whether Kyle had been punched in the face and pushed into a chair while in the office, the Officer responded:

No, that, none of that happened … There was no assault that I witnessed.

He told us he could not recall exactly how he came to be in the office but said the Supervisor had likely asked him in. He noted ‘typically you wouldn’t want to be … in a room by yourself with someone who’s just verbally abused officers’. The Officer also noted that it was generally good to have more than one set of eyes present ‘in case something does happen’.

The Officer recalled Kyle sitting in a chair, ‘still pretty amped up’ about not getting a call to his lawyer.

He said Kyle was crying, and saying ‘he doesn’t know anything about … the rules and stuff like that … He was … swearing and stuff’.

The Officer said he got a cup of water and some tissues for Kyle, ‘for his tears’. He said either he or the Supervisor dialled Kyle’s lawyer on the office phone and allowed Kyle to speak to her.

Unlike the Supervisor, the Officer made no mention of Kyle pacing or hearing voices. When we asked him about Kyle’s mental state he said while Kyle had seemed distressed at first, he had calmed and ‘seemed fine’ after the phone call. He said Kyle had thanked him and the Supervisor as he left the office.

In response to a draft of this report, the Officer repeated his strong denial that any force was used against Kyle. He disputed any suggestion that he ‘took Kyle to ground’ or forcibly pushed him into a chair. He stated ‘at no time’ did he touch Kyle, and maintained the closest they got was when he handed Kyle a cup of water. He also rejected any suggestion he had witnessed the Supervisor use force, or that he had failed to intervene to protect Kyle.

Other evidence

CCTV

CCTV blind spots hindered our investigationFootage from fixed CCTV cameras and body worn cameras can be especially useful in resolving conflicting accounts of prison incidents.In this case, the conversation with Kyle to address his behaviour was held in a CCTV blind spot. There is no camera in the Supervisor’s office, and general duties officers do not routinely wear body worn cameras at Ravenhall. In response to this report, Kyle commented: ‘It’s just easier if there are cameras. They should have voice activation so when you walk into a room they turn on’. We acknowledge it is sometimes necessary for officers to isolate people in prison from others to speak about behaviour or welfare. However, having such conversations in a private but monitored area better protects everyone involved. As our June 2022 use of force report noted, when incidents occur in CCTV blind spots, the officers involved can face suspicion about their actions and motives in choosing an unmonitored area. In response to our 2022 report, the Department accepted a recommendation to issue formal guidance to officers requiring them to use CCTV-monitored areas, wherever possible, for behaviour-related conversations. The Department also advised the policy for body worn cameras had been strengthened to explicitly require staff to activate a body worn camera when addressing the behaviour of people in prison in an area not covered by CCTV. |

We reviewed CCTV footage from four relevant cameras in the unit.

In relation to this allegation, we consider the most important images are those showing Kyle walking back to his cell from the Supervisor’s office cradling the left side of his face, and those captured about an hour later, showing Kyle continuing to touch and rub his face, and exploring the inside of his mouth with his tongue (see Figure 4).

No injuries are visible in any of the CCTV shots, though given Kyle’s accounts of a split inside his lip and a bloody nose, it is unlikely these would be seen.

We showed the Supervisor and the Officer the footage of Kyle walking back to his cell straight after leaving the office. Neither explained why he might be touching his face.

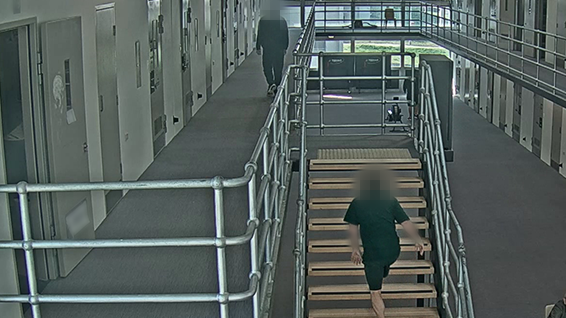

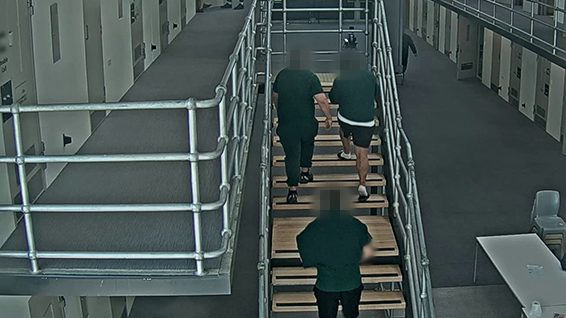

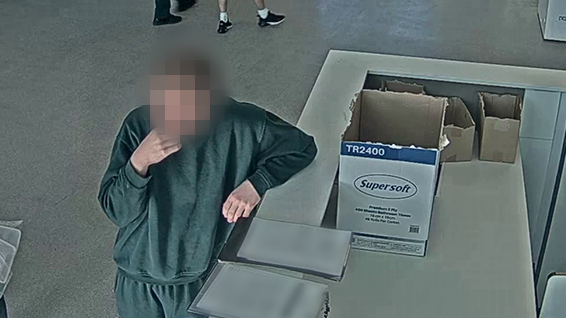

Figure 4: CCTV and other images of Kyle’s facial discomfort

Sunday 21 August 2022

10.11am Two different camera angles capture Kyle holding his right hand against the left side of face as he leaves the Supervisor’s office after the alleged assault.

———

11.11am Kyle holds his face as he returns to the Supervisor’s office to request nicotine patches about an hour later.

———

11.13am Kyle probes his mouth with his hand and tongue as he waits to see the Supervisor the second time.

———

11.16am Kyle cradles left side of face on return from

the second office visit.

———

Next morning Kyle’s photographed injuries include fat lower-left lip.

———

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on Ravenhall CCTV recordings and Kyle’s medical file.

Another section of the footage potentially relevant to this allegation occurs at 10.21am. Kyle is in his cell with some other people on remand, including one present during a later incident discussed in Allegation 3.

A camera captured reflections on the door of vigorous movement inside Kyle’s cell, which could potentially indicate another assault on him.

When we asked Kyle about this at interview, he said some of the people in the cell were mates, and one was not. He said that they had all just been talking. He reiterated this after seeing our draft report.

A third section of footage we examined closely showed several movements of curtains in the Supervisor’s office while Kyle was inside, and an instance where onlookers turned as if they had heard noises from within. In our view it is unlikely any curtain movement or noises related to the alleged use of force on Kyle.

Adam

We spoke with Adam, who was also on remand in Kyle’s unit. His accounts are of interest because he had contact with Kyle before the alleged assault, was near the office while Kyle was inside, and followed Kyle back to his cell straight afterwards.

As was the case with Kyle and the officers, by the time we spoke with Adam he had already provided multiple accounts of that day to others.

Some of the sworn evidence Adam gave us in relation to this allegation was not consistent with what he had earlier told the GEO Investigator.

Most notably for this allegation, Adam told GEO that Kyle had no injuries after the alleged assault in the office. However, Adam’s evidence to us and to Corrections Victoria was that he saw injuries to Kyle’s eye and lip.

Adam told us he followed behind Kyle as he returned from the Supervisor’s office to his cell. Adam recalled Kyle was ‘pretty frantic’ and seemed ‘very scared, shook up, frightened, very intimidated and lost’.

Adam said Kyle told him that officers had punched him in the face and thrown him to the ground. Asked to describe any injuries he saw, Adam said:

There was a big cut in his lip. His nose may have been bleeding a little bit out of one side and I think his eye was a bit puffy …

We asked Adam why he told a different version of events to GEO. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2. In short, Adam told us he felt ‘too scared’ to give an accurate account when interviewed by GEO because he feared a uniformed officer who accompanied the GEO Investigator was ‘mates’ with the Supervisor. He also said he felt intimidated because the interview room lacked CCTV cameras.

Adam also gave GEO information he did not give us about possible motivations for an assault on Kyle by other people in prison. This is discussed more in the section on Allegation 3.

Some inconsistencies we noticed in Adam’s accountsThere were some inconsistencies in Adam’s various accounts. We considered these when making our findings.Adam’s perception of time is, by his own admission, ‘the worst’. When we first asked him to talk us through the events of 21 August 2022, his recall was quite muddled. After he reviewed CCTV excerpts, he provided a more linear account. Adam’s recall of Kyle’s injuries was also imprecise. He consistently identified the eye and lip as damaged, but flipped between it being the right or left side of the lip. As noted earlier, human memory is flawed, and given we spoke with Adam more than a year after the incident some inconsistency is understandable. Our impression of Adam was that he was well-meaning in agreeing to speak with us, in circumstances where many other people in prison likely would not. He declared upfront that he had previously had ‘a bit of an argument’ with the Supervisor, though said his motivation in speaking to us was purely to improve ‘the system’. |

The peer listener

About half an hour after the alleged assault on Kyle, the Supervisor asked the unit’s peer listener – a person on remand who lends an ear to others – to check on Kyle.

We reviewed notes made of the peer listener’s interview with the GEO Investigator.

The peer listener recalled going to Kyle’s cell and speaking with him, in the presence of some others. Multiple people had been in and out of the cell before him, and his visit was after CCTV captured reflections on Kyle’s door showing vigorous movement inside.

The peer listener told GEO Kyle had mentioned a sore mouth but had not said how the injury occurred, and the peer listener had not asked why. The peer listener said he did not see any blood, but that Kyle’s lip was ‘a bit swollen’, prompting him to fetch some frozen vegetables for Kyle to use as an ice pack.

Finding on Allegation 1

Allegation 1 finding in shortOn balance, we find the allegation that on 21 August 2022 the Supervisor and the Officer used unreasonable force on Kyle is partially substantiated.We find the Supervisor struck Kyle. This was unnecessary and avoidable, and therefore not authorised pursuant to Section 23 of the Corrections Act. The Supervisor’s actions also appear unlawful within the meaning of Section 38(1) of the Human Rights Charter. We do not consider the Officer used unauthorised force. However, he did not intervene to protect Kyle from the Supervisor. We find this was contrary to Section 20 of the Corrections Act which requires officers to take all reasonable steps for the safe custody and welfare of people in prison. Corrections Victoria’s investigation into these events found that the Supervisor’s actions represented ‘an assault by staff on a prisoner’. However, the Supervisor and the Officer have both always strongly denied that any force was used against Kyle in the office. They reiterated this in response to our draft report and expressed strong disagreement with this finding. GEO’s investigation did not substantiate the use of any force in the office, and the company stood by its finding in its response to our draft report. |

In reaching a finding on this allegation, we needed to determine whether force was used on Kyle, and if so, whether it had a lawful basis and was reasonable in the circumstances.

Was force used on Kyle?

Kyle’s description of being struck to the left side of the face by the Supervisor has been largely consistent in its telling over time.

This includes – within 24 hours – to other people in prison, to his parents by phone, and to prison officers and medical staff. In later weeks and months he also provided similar descriptions to us and the GEO Investigator.

It is reasonable to wonder why Kyle did not mention an assault by officers at the first available opportunity – during the call to his lawyer from the office. We accept Kyle’s explanation that he felt too intimidated to say anything with the officers beside him.

CCTV footage provides the next most timely perspective. It shows Kyle touching the left side of his face almost immediately upon leaving the Supervisor’s office. In our view, in combination with other evidence we reviewed, this supports a finding that force was used behind the closed office door.

While no injuries are clearly visible on CCTV footage, Kyle’s apparent ongoing facial discomfort, especially around the lower lip, is evident in images captured from various angles in the next hour or so.

The areas he touches align with his verbal accounts, and with medical records from the day after the alleged incident which describe bruising and swelling to Kyle’s left lower lip and a small cut near his left eye.

A further support for our finding that force was used is the account of Adam, who saw and spoke to Kyle minutes after he left the Supervisor’s office.

Importantly, Adam’s interaction with Kyle happened before anyone else came to the cell.

Adam recounted seeing injuries and swelling, and said that a clearly rattled Kyle told him officers were responsible.

While Adam gave different evidence to GEO – that he had not seen any injuries on Kyle – in our view his reason for this was understandable and does not discredit his evidence to us. This is discussed more in Chapter 2.

Further, we note that Adam had little or nothing to gain by voluntarily co-operating with our investigation. People in prison are often reluctant to become involved in issues due to a fear of reprisals or victimisation, and it is a credit to him that he participated in this process.

Our finding that the Supervisor used force is further supported by the peer listener’s evidence. He saw an upset Kyle with a swollen mouth and got him an ice pack about 40 minutes after the alleged office incident.

We note that by then, quite a few other people in prison had already been in and out of Kyle’s cell. It is possible one or more of them might have assaulted Kyle in the period between Adam leaving and the peer listener arriving.

Most notably, CCTV captured unusual reflections on Kyle’s cell door at about 10.21am. It is possible that the burst of activity inside the cell which produced rapidly moving shadows on the door was an assault on Kyle.

However, we note Kyle has never complained about any such incident – including after seeing a draft of this report. His accounts consistently describe only two assaults that day – one by the Supervisor, and another at the hands of the trio which he says happened well after the peer listener saw him (see Allegation 3).

While Adam and the peer listener both reported seeing damage to Kyle’s face, no injuries are conclusively visible in CCTV images.

The Supervisor and the Officer have consistently stated they did not use any force at all on Kyle. They reiterated their strong denials after reading draft extracts of this report. They maintain that their primary reasons for interacting with Kyle that day were to discuss his welfare and mental state, and to improve his understanding of prison rules.

The Supervisor’s descriptions of Kyle’s mental health while they were in the office included Kyle sobbing hysterically and saying he was hearing voices. In our view, the fact the Supervisor did not refer Kyle to medical or psychological support that day tends to undermine his accounts of how unwell Kyle was.

CCTV footage is also inconsistent with the Supervisor’s description of Kyle pacing back and forth and crying upon entering the office. Footage we reviewed shows Kyle standing still and seemingly calm as he waited outside.

Further, the Supervisor told us Kyle had been naked during head counts and sent ‘spam’ messages on his InCell device. However, Kyle denies doing either, and we could not find any warnings for this on Kyle’s file.

The second element to the alleged use of unreasonable force was whether the Supervisor and the Officer took Kyle to ground after the alleged punch, then picked him up and shoved him forcibly into a chair.

Both officers have always disputed – and continue to – Kyle’s various accounts of what happened in the office that day.

In his response to a draft report extract, the Officer maintained that he had not touched Kyle, and that the closest he got was when handing him a cup of water. The Officer’s response also queried the differences in Kyle’s accounts outlined in the draft report extract.

Beyond the statements of the three people in the office, there is no other direct evidence available about this aspect of the use of force. Medical reports do not attribute any specific injuries to Kyle being taken to ground or pushed to sit in a chair.

On balance, based on available evidence, we did not substantiate that the Supervisor and the Officer took Kyle to ground and forced him into a chair.

Was there a basis for using force?

The Corrections Act allows prison officers to use reasonable force ‘where necessary’ in certain circumstances.

We find that none of the circumstances outlined in the relevant Commissioner’s Requirement or Ravenhall Operating Instruction applied when the Supervisor punched Kyle in the face. The force used did not have a lawful basis.

Kyle admits to swearing at the officers immediately before he was struck, an obvious act of ill-discipline. However, the Commissioner’s Requirements make it clear that physical force is a last resort for officers and that ‘negotiation and communication’ are the core tactical options available.

The Supervisor’s use of force exceeded what was required to control the situation, and was not balanced against the risk of injury to Kyle.

We consider the unnecessary and avoidable punch was therefore not authorised by Section 23(2) of the Corrections Act.

The Supervisor’s actions also appear unlawful under Section 38(1) of the Human Rights Charter, as the punch was incompatible with the right to protection from cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment under section 10(b) and the right to humane treatment when deprived of liberty, under section 22.

In response to a draft extract of this report, the Supervisor did not agree that he acted contrary to the Corrections Act or in a manner inconsistent with the Human Rights Charter.

While we do not consider the Officer used unauthorised force at any stage during the events in the office, we did not identify any evidence he intervened to protect Kyle from the Supervisor. We find this inaction was contrary to Section 20(2) of the Corrections Act which requires officers to take all reasonable steps for the safe custody and welfare of people in prison.

In response to a draft report extract, the Officer maintained his insistence that no force was used. He strongly disagreed that he witnessed a use of force or failed to intervene to protect Kyle.

GEO’s investigation did not substantiate the use of any force in the office, and the company stood by this finding in its response to a draft of this report. You can read the company’s full response at Appendix 2.

Allegation 2 – InCell device disabled

The second allegation centred on whether the Supervisor misused his position to restrict Kyle’s InCell device, limiting access to medical and other help.

About InCell devicesEach cell at Ravenhall has an ‘InCell’ device. It enables users to access induction materials, interactive video learning, a digital library, the prison canteen, a timetable of scheduled activities and other services.People can also use their InCell device to make a complaint, submit a medical request, and to message certain prison staff, such as case officers. Ravenhall’s InCell System Operating Instruction at the relevant time directed that people in prison ‘be given access to all aspects of InCell unless there are reasons to limit or prohibit user access’. If access was limited or prohibited, the Operating Instruction required reasons to be noted on the person’s file, along with any remedial strategies. However, the Operating Instruction did not provide clear guidance on acceptable reasons to restrict InCell access. It was also unclear on who had authority to restrict access, and for how long. In response to a draft report extract, the Supervisor said the InCell system was being ‘rolled out’ at the time of the events in question and there were ‘teething issues’. He stated that ‘many’ people on remand at Ravenhall were left without InCell access ‘for several days (and up to a week) after arriving at a unit’. He stated this was due to a shortage of devices and IT delays. GEO told us in response to our draft report that it had clarified its policy on InCell and communicated this with staff in the wake of the incident involving Kyle. The Department has also amended a relevant Commissioner’s Requirement. This issue is discussed more in Chapter 3. |

Kyle unable to log medical request via InCell

Kyle told us when he returned to his cell after the alleged office assault (see Allegation 1), he tried to request a medical appointment ‘pretty much ASAP’ via his InCell device. However, the system would not let him log on.

We obtained and reviewed InCell system access logs for the day in question. They show that within two minutes of Kyle leaving the office, the Supervisor totally disabled Kyle’s InCell access.

Access to healthcare in prisonThe Corrections Act gives every person in prison the right to access reasonable medical care and treatment. At Ravenhall, people submit requests for medical appointments via the InCell device or through a paper form lodged in a letterbox cleared daily. The relevant Operating Instruction encourages the use of InCell for self-referrals, with paper forms used as a backup if the system is down. Officers are required to assist people in prison if they are having difficulty lodging a request. People who are acutely unwell or have an urgent health matter are encouraged to approach an officer, with staff expected to contact nurses immediately for advice. |

The Supervisor’s reasoning

The Supervisor’s short entry on Kyle’s file that day did not refer to disabling the InCell. Nor did his later incident report.

At interview, the Supervisor confirmed to us he had disabled Kyle’s InCell system access, and offered several reasons for the deactivation.

One he gave was that Kyle had been ‘spamming’ officers and sending ‘inappropriate messages’ using the InCell device. However, Kyle denied this when shown a draft report extract. He said he had used his InCell in the days before the incident to book a dental checkup, but not to message officers. We found no record of ‘spamming’ in Kyle’s file.

Another reason the Supervisor offered to us was that the deactivation was to discipline Kyle ‘on the grounds that [Kyle] was abusive to staff’, which is an offence under the Corrections Regulations.

A third reason the Supervisor gave for disabling Kyle’s InCell device was his ongoing concern for Kyle’s mental health. He explained there was sometimes a risk of delayed responses to requests for help raised via the device, and he wanted to avoid this by having Kyle directly approach an officer with any concerns.

The Supervisor told GEO he had not warned Kyle he would be switching off the device. The Supervisor told us he told Kyle as he exited the office: ‘Look, if you need anything again, come and speak to me’.

The Supervisor also noted the risk of a delayed response to InCell self-referrals in his interview with the GEO Investigator. He explained switching off the InCell was his way of encouraging engagement with officers.

However, in an email chain we saw about GEO’s investigation report, Ravenhall’s General Manager observed that disabling InCell for mentally unwell people in prison was not an endorsed practice.

Revoking privileges for minor offencesThe Supervisor told us his role allowed him to make an ‘ad hoc’ decision to take a person’s privileges away. Commissioner’s Requirement 2.3.3 Disciplinary Process and Prisoner Privileges sets out steps that must be followed to investigate an alleged offence. Once satisfied a minor offence has occurred, Disciplinary Officers may withdraw one of a list of approved privileges for up to 14 days as a penalty. There were 13 items on the list of privileges for 2022, including access to canteen spends, television, sport and hobby activities. InCell system access and medical treatment are not listed as privileges. Further, section (50)(5) of the Corrections Act requires disciplinary officers to record offences. The Supervisor said he recorded his decision to switch off the InCell on Ravenhall’s ‘Minor Offence Register’, which he said was ‘a book’ at the officer’s post. |

Figure 5: Supervisor’s accounts over time of disabling Kyle’s InCell device

21 August 2022: The Supervisor’s note on Kyle’s file about allowing him a call to his lawyer from his office to ease distress does not mention InCell. 29 August 2022: In his formal incident report about the alleged assault, the Supervisor makes no mention of switching off Kyle’s InCell. 30 August 2022: Asked about InCell by the GEO Investigator, the Supervisor says he ‘pulled the applications’ from Kyle’s device, but did not tell Kyle he’d done so. He says he held concerns for Kyle’s mental health and wanted him to contact a staff member directly if he needed help. 4 August 2023: The Supervisor provides multiple reasons to us during an interview for turning off the device: to stop Kyle ‘spamming’ officers; to discipline him for abusing officers; and out of concern for Kyle’s mental health. 20 November 2024: Responding to a draft of our report, the Supervisor says it was not technically possible for him to isolate certain InCell functions. He says to shut off messaging or remove a person’s access to privileges (such as television), officers had no choice but to disable the entire InCell device. |

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on supplied documents

Finding on Allegation 2

Allegation 2 finding in shortThe allegation that the Supervisor misused his position to restrict Kyle’s access to the InCell device, limiting access to help and medical services, is substantiated. The Supervisor had neither express authority nor a legitimate reason to disable Kyle’s InCell. In response to a draft of this report, the Supervisor disagreed that he acted contrary to the Corrections Act or in a manner that is inconsistent with the Human Rights Charter. |

In our view, the varying reasons the Supervisor provided for restricting Kyle’s InCell system access are not supported by the available evidence, and we do not accept any of them.

By disabling Kyle’s InCell access, we find the Supervisor breached section 47(1)(f) of the Corrections Act, which gives people in prison a right to access medical treatment.

The Supervisor’s actions also appear to have been unlawful under section 38(1) of the Human Rights Charter, as disabling the device was incompatible with the right of persons deprived of their liberty to be treated humanely under section 22.

In response to a draft report extract, the Supervisor disagreed that he acted contrary to the Corrections Act or in a manner that is inconsistent with the Human Rights Charter.

The Supervisor maintained during the time Kyle’s InCell device was disabled, Kyle had access to a hard copy form to request medical help or could have approached the nurse during daily medication rounds.

While it is true Kyle could still have later lodged a hard copy form or perhaps approached another officer or a nurse, the fact remains Kyle’s efforts to seek medical help via the InCell device were blocked by the Supervisor’s misuse of his position.

We were disturbed by the Supervisor’s comments in response to a draft of this report stating that officers at his level could not isolate specific InCell functions and had no choice but to ‘disable the entire device’.

The Supervisor supported the idea of improved training and clarity around InCell access in his response to a draft report extract. He also queried whether the heavy workload of prison officers at the time played a role in apparent failures to keep detailed and timely written records.

GEO stated in its response to our draft report (see Appendix 2) that disabling InCell was not an endorsed practice, and that it had clarified its policy on InCell and communicated this with staff in the wake of the incident involving Kyle.

Allegation 3 – Supervisor influences others to assault Kyle

The third allegation was that on 21 August 2022, the Supervisor misused his position to influence a trio of people in prison to assault Kyle.

What Kyle says happened

Kyle has given multiple accounts of an alleged assault by the trio in his cell in the wake of the incident in the Supervisor’s office.

His versions of these events have broadly aligned, except for one major discrepancy – his reason for visiting the Supervisor’s office a second time. This is discussed further below, and in Chapter 2.

Figure 6: Kyle’s accounts over time of the alleged assault by the trio

1.42pm Sunday 21 August 2022: In a recorded call to his mother, after saying the Supervisor had punched him, Kyle adds ‘the screw denied it and got other prisoners involved to punch the fuck out of me too’. 3.29pm: In a recorded call with his father, Kyle says the Supervisor ‘got all the boys to come in my cell and bash the fuck out of me, pretty much. So I got assaulted twice’. 8.05am Monday 22 August 2022: Kyle tells an officer who asked about his obvious lip injury that he has been assaulted by a staff member, and then by some other people in prison who he could not name. The incident report quotes Kyle saying: ‘The Supervisor put a hit on me. If I say anything, they will come after me again’. 8.35am: In an interview with the duty supervisor, Kyle says he was first assaulted by officers, then by the trio whose names he did not know. 8.47am: Kyle tells a nurse assessing his injuries that he has been assaulted by an officer, and then by the trio. 29 August 2022: Kyle tells the GEO Investigator that the trio had ‘pretty much got stuck into me’. He says all three ‘had a go’ at punching him in the ‘same spot’ as the Supervisor, and that he thinks the Supervisor might have put them up to it. 21 October 2022: Kyle tells Corrections Victoria the trio entered his cell and king hit him. He says they also told him to stop ‘ratting’, show officers respect, and to ‘buzz up’ on the intercom to request a move to another unit. 6 July 2023: Kyle tells us the trio entered his cell and punched and kicked him. He says they told him to ‘leave all the guards in fucking peace’ and that he had to leave the prison. |

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on supplied documents

Nicotine in Victorian prisons

Smoking is not allowed in Victorian prisons. However, at the time of the alleged incidents, some people in prison were able to access nicotine replacement therapy. Eligible people were given a nicotine patch each day if they returned their used patch from the day before. Some people were known to misuse the patches to create cigarette substitutes. The supply of nicotine patches in prisons ended on 26 February 2024. |

Second visit to Supervisor’s office

Kyle told us after the incident in the Supervisor’s office described in Allegation 1, he returned to his cell and told some other people about it.

He said one of them mentioned the Supervisor issued nicotine patches as part of a prison program, and essentially suggested Kyle ‘bargain’ with the Supervisor to ‘try and get us some smokes’ in return for not reporting the use of force.

Kyle told us he felt pressured by others to approach the Supervisor but had decided to go along with the idea:

I did feel like it was a bit, you know, ‘You’ve got to do it’, sort of thing. I didn’t really want to do it but then I thought, fuck it, why not? Get something for the boys and me … And obviously that’s when I’ve done what I’ve done.

Kyle said he went into the Supervisor’s office and – alone and with the door closed – put a proposal to him:

… I said, ‘Hey, obviously you assaulted me. Can we do something about it? Can you give me some patches or something? … no one else needs to know, just between me and, just yeah’.

Kyle said when the Supervisor replied ‘You ain’t getting any patches’, he again swore at the Supervisor and walked out.

However, while Kyle told us his second visit to the Supervisor’s office was to seek nicotine patches, he told the GEO Investigator it was to request medical attention because his InCell device was disabled:

I said ‘… you’ve assaulted me can I at least get some medical attention or something like that’, and he said ‘You’re not getting it’ pretty much …. I also asked him ‘Can you also approve my lawyer’s phone list’ or whatever. He said ‘Yeah, I can do that for you but you’re not getting medical attention’.

When we asked Kyle why he’d told GEO something different, he said he was reluctant to admit having asked for the patches:

I felt ashamed actually mentioning that during the process, the interview. I didn’t really want to, yeah, I just felt ashamed just mentioning the patches …

The rest of Kyle’s interview with the GEO Investigator was broadly consistent with the version of events he later provided to us.

Alleged assault in cell

Kyle told us not long after his second visit to the Supervisor, the trio came to his cell, ordered his friends out, and began to hit his head and gut, and to kick him.

He said some of the blows hit the same part of his head as the Supervisor’s earlier strike. He said in addition to the damage to his lip, he suffered a bruise behind his ear and a bruise on the nose.

He recalled the men ordered him to ‘leave everyone alone. Leave all the guards in fucking peace. Don’t fucking rat, don’t dog’.

He said the men ordered him to ‘buzz up’. Kyle interpreted this to mean he should use the intercom to request to go to another area or prison.

Kyle said soon after the men left his cell, he used his intercom to contact officers. A recording of this call at 11.31am captured the brief exchange:

An officer: Go.

Kyle: I’m fearing for my life – I want out.

Kyle told us he was scared what else might happen to him, and that he might ‘get got’ – by which he meant stabbed or possibly killed:

I just wanted out. I just had enough. I just wanted to be safe, that’s all I wanted, you know what I mean?

He told us soon after he made the intercom call, two officers attended his cell. He said one asked who had assaulted him and Kyle recalled saying: ‘I can’t tell you. If I tell you, something will happen’. We discuss this intercom call, and a second that Kyle made about an hour later, in more detail later in this report.

What made Kyle think the Supervisor was involved?Kyle told GEO he was never directly told by the trio or by prison staff that the Supervisor had ordered an assault. Kyle told us several things had nevertheless led him to think the Supervisor was somehow involved. He said he had thought from the day he arrived at Ravenhall that the Supervisor seemed close with the three men. ‘You’d see them always up near the office there, talking to him. Like not just, “How are you going,” they were actually talking to him’, he recalled. Kyle said the timing of the three men arriving at his cell barely an hour after being punched by the Supervisor and so soon after his unsuccessful request for nicotine patches had left him thinking there must be a link between the incidents. He recalled telling the Supervisor multiple times that he would be reporting the punch, and speculated that the Supervisor had perhaps sent the trio to discourage him from speaking up: I reckon the [Supervisor], from my belief, I’m not 100 per cent sure, that he’s told them, ‘I’ll give you something on the side. Just, you know, go and sort him out’. Kyle said when he asked the trio why they had assaulted him, they said ‘[be]cause of what you’re fucking doing’. He said both during and after their assault, the men had referred to keeping quiet, and to leaving the guards alone. Similarly, Kyle told GEO that when he asked the trio ‘why is this going on?’, they had replied: ‘Don’t aerate and show the officers some respect…’. (Kyle later told us ‘aerate’ in a prison context meant ‘don’t bring heat on to other people’.) Kyle also told GEO that following the trio’s alleged assault he asked his friends ‘what do you reckon’s happened here?’. He said they had commented on seeing the trio talking to officers beforehand, and that this had contributed to him thinking the Supervisor was involved. |

About billetsSome people in prison are assigned to ‘billet’ roles, performing day-to-day activities such as cleaning, laundry, meal preparation and other general duties. The Officer told us people in prison usually expressed interest in the roles ‘to make some extra money’ and ‘to have some structure in their day’. He said typically supervisors appointed the billets, based on suggestions from other officers: Because there’s always spots coming up, especially in, you know, the remand, having people in and out, you need billets coming in and out. So officers as well could … basically choose and suggest prisoners to be billets. |

What the Supervisor says happened

The Supervisor told us when Kyle came to see him the second time, it was to ask for nicotine patches – a request he refused.

In contrast with Kyle’s account of the patches being in return for not reporting the alleged punch, the Supervisor instead recalled Kyle saying along the lines of ‘Look, the boys are not going to … leave me alone unless you give me nicotine patches’.

He said this made him think someone ‘may be standing over’ Kyle.

The Supervisor said Kyle had previously been taken off the nicotine replacement program for giving his patches to somebody else:

So basically, he said, ‘You need to put me back on the patch or else, you know, like, or else they’re just going to,’ whatever. I said to him, ‘Look, that’s not how it works. You can’t get back on the patch once you’ve been taken off.’

The Supervisor also told GEO Kyle had been removed from the nicotine patch program. However, Kyle told us he had never been on it at Ravenhall and GEO’s investigation confirmed Kyle had never been on the program.

Further, we did not identify any evidence that the Supervisor logged an incident report or made note of his suspicions that Kyle was being stood over for nicotine patches.

The Supervisor told us when he refused Kyle’s request for patches, Kyle became frustrated and began swearing and saying things like

‘I don’t fucking know the rules around here’.

He told Kyle he would send the unit’s ‘Induction Billet’ – a person in prison whose job is to help people settle in – to ‘have a word’ and ‘explain the rules of the unit’.

The Supervisor said by ‘explain the rules’, he meant the GEO rules, and also the ‘internal rules’ among the prison population such as ‘don’t talk to the officers, don’t steal another prisoner’s food, those internal politics’.

He explained that, after Kyle left, he had called the Induction Billet into the office, and that he had arrived with the other two members of the trio ‘because they are always together’.

The Supervisor said though the others were present, he had spoken only to the Induction Billet. He described himself as ‘annoyed’, and said he had ‘challenged’ the billet:

I go, ‘Look, if this kid’s coming in here, he doesn’t know how things work and you’re essentially not doing your job’ ….

…

And I said to him, ‘Look, can you have a word with [Kyle]? Look, he just needs a bit of a rundown on, like, you know, how prison operates, things like that?’. And then he said, ‘Yes’ … then he left the office. I remained in the office and that was that.

The Supervisor’s account of this conversation to GEO was slightly different. He told GEO that he had specifically asked the Induction Billet to discuss the request for nicotine patches:

I said ‘Can you have a word with [Kyle]? Yeah. I think he’s getting stood over for the patch’ and he goes ‘Yeah, sweet’. And then, yeah, they left the office and I stayed in the office and then that was it.

The Supervisor told us and GEO he was unaware all three men had gone straight to Kyle’s cell.

In response to the allegation that he influenced the men to assault Kyle, the Supervisor told us he was ‘not answering that due to legal advice’.