‘We just want to finish our home’: Management of domestic building insurance claims by VMIA

Date posted:

Warning

This report contains language some readers may find offensive.

Privacy

To protect people’s privacy, this report has been deidentified. All the names used are pseudonyms.

Summary

[I]f this process was designed to make people give up, it’s perfectly designed …

– Homeowner

He said COB today but we don't have COB

– DBI team member

What we investigated

In Victoria, if a builder has died, disappeared or become insolvent, homeowners are protected by Domestic Building Insurance (‘DBI’). They can claim for incomplete or defective work so they can complete their home.

In March 2023, Porter Davis Homes Group (‘Porter Davis’) collapsed. This was the biggest builder insolvency in Victoria’s history. In the six weeks following the collapse, the Victorian Managed Insurance Authority (‘VMIA’) received more DBI claims than it had in the entire previous financial year.

The Legislative Council required the Ombudsman to investigate VMIA’s management of DBI claims. We considered VMIA’s actions both before and after the Porter Davis collapse, with a focus on its:

- preparedness for a major builder insolvency

- claims process

- timeliness in processing claims

- communication with homeowners

- handling of disputes and complaints.

We also considered how DBI claims handling could be improved.

Why it matters

For most people, building or renovating a home is one of the biggest projects they will ever undertake. When a builder becomes insolvent, the impact is immediate and significant, putting housing dreams in jeopardy and throwing lives into turmoil.

This uncertainty can create acute stress for affected homeowners, straining finances, relationships and mental health. Often, people must pay to stay somewhere else until a new builder is lined up and work is completed, or live alongside defects until they’re fixed.

DBI is intended to support and protect homeowners through this upheaval, noting it is an insurance product, not a compensation or hardship fund. And it seems for many homeowners, making a DBI claim through VMIA was straightforward.

However, we also heard from some deeply frustrated and distressed homeowners. Their experiences – even if only a small proportion of total claims – offer important insights for improving the future administration of DBI in Victoria. This will ensure the scheme remains both fair and financially viable.

What we found

- VMIA had taken some steps to prepare for large builder insolvencies, but these were only partly effective. While the scale of the Porter Davis collapse was unprecedented and VMIA had limited time to prepare, it should have started planning for it sooner.

- VMIA’s process and the changes it made to deal with the Porter Davis collapse were reasonable and legal, however, some individual actions led to unfair outcomes, especially in complex claims. VMIA’s engagement of volume builders worked well for many homeowners, but its lack of transparency was a source of frustration and stress. The use of law firms to help process more claims quickly was seen by some people as too adversarial. VMIA failed to effectively communicate its decisions and intentions to homeowners, creating a justifiable perception of unfairness.

- On average, there was no unreasonable delay in claims processing for Porter Davis homeowners, but where significant delays occurred, the process caused unreasonable personal and financial hardship for people. Average claims processing times reduced but as there was little transparency around timelines, homeowners’ expectations were often far from the reality.

- VMIA’s communication with homeowners was inadequate and lacked transparency. Homeowners received little information about how claims were managed and how long the process would take. VMIA’s external call centre could not answer substantive questions about claims. Homeowners were frustrated with VMIA’s delay or failure to respond to online messages via a dedicated portal. VMIA’s communications after the Porter Davis collapse fell short of its obligations as a public sector body to be fair and transparent.

- VMIA’s dispute handling processes and practices met VMIA’s legislative obligations, but were not always fair and reasonable. VMIA did not always advise homeowners that they could ask for a decision to be revisited and there was no documented review procedure at the time of the Porter Davis collapse. The only formal pathway for disputing decisions was through VCAT, a costly and time consuming option.

Overall, VMIA achieved a reasonable outcome for most homeowners with DBI claims, both before and after the Porter Davis collapse. However, for some, especially those living in a home with ongoing defects, the DBI scheme did not live up to its purpose. As a government body VMIA should have exercised more discretion within the bounds of the DBI policy to achieve fair and timely outcomes.

The need for DBI system reform has been recognised by recent legislative changes. However, more needs to be done to improve DBI management processes, communication with homeowners and overall system transparency.

How VMIA responded

VMIA views its performance in managing DBI differently to the Ombudsman. It does not accept that some homeowners received unfair outcomes, and maintains that all claims were determined in line with DBI policy terms.

VMIA recognised the toll that the Porter Davis collapse had on its staff, and commended their performance in difficult circumstances.

While defending its performance, VMIA acknowledged that its communications were inadequate in some respects and said it had made improvements in this area. It also conceded that a relatively small number of homeowners had a poor experience:

To those homeowners who had a difficult experience making a claim with us, we have listened, learned, and changed … For those few where we did not do well enough, we are sorry.

You can read VMIA’s response letter in Appendix 2.

What needs to change

Responsibility for DBI recently transferred to the Building and Plumbing Commission. We have made nine recommendations to the Commission intended to:

- clarify and improve DBI policies

- allow the Commission to more effectively scale up its workforce when there is a large insolvency

- improve communication

- enhance transparency.

We also endorsed three recommendations made by the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office. Our recommendations are set out in full later in this report.

Background

In Victoria, people undertaking domestic building projects – such as building or renovating their home – are protected by Domestic Building Insurance (‘DBI’). This is a ‘last resort’ insurance scheme, meaning that homeowners must first try to resolve any issues with their builder.

However, sometimes that is not possible, including when a builder has died, disappeared or become insolvent. In these situations, a homeowner may be compensated under their DBI policy for the loss resulting from work not being completed or it being defective.

All domestic building projects costing over $16,000 must be covered by DBI. Builders are responsible for purchasing DBI on behalf of the homeowner but it is the homeowner who ultimately claims on the policy. This is one of the reasons DBI is different from most other types of insurance.

Builders must provide homeowners with a copy of their certificate of DBI insurance and the policy terms and conditions. This usually happens when the building contract is signed.

Theoretically, this informs homeowners about how DBI works and what it covers. In practice, however, many homeowners do not fully understand the policy and know little about DBI until they have to use it.

Historically, DBI was provided by various private insurance companies. However, several insurers stopped offering DBI around 2010.

In 2010 the Government amended the Building Act 1993 to designate the Victorian Managed Insurance Authority (‘VMIA’) as a DBI provider. During the second reading speech in Parliament, the Honourable Jenny Mikakos, former Parliamentary Secretary for Planning, stated:

The volatility in recent times of insurers entering and leaving the [DBI] market has led to the state government decision to intervene and provide builders and consumers with an affordable insurance scheme.

VMIA advised that it was directed to offer DBI to the public within the existing scheme on commercial terms, alongside private insurers.

The Government’s intervention was designed to protect the Victorian economy by supporting the state’s construction industry, and to protect Victorian consumers. At the time, the Government recognised that:

... for most Victorians the biggest outlay of expenditure that any of them will make in their lifetime will be the purchase of their own home ... For most, building or renovating a home is an exciting and satisfying process, but for a small minority it can bring a great deal of stress and in some circumstances even end in disappointment ... as with all consumer protection legislation, there needs to be a strong framework to protect the rights of homeowners.

Why we investigated

In recent years, the number of building companies going out of business in Australia has increased. Some of these builders, like Privium Pty Ltd and Snowdon Developments Pty Ltd, were large companies and they left behind hundreds of unfinished homes.

On 31 March 2023, Porter Davis Homes Group (‘Porter Davis’) collapsed. This was the biggest builder collapse in Victoria’s history, affecting over 1,700 homeowners nationally.

In the six weeks following the Porter Davis collapse, VMIA received more DBI claims than in the entire previous financial year. A quarter of these were lodged in a single day. This put an unprecedented demand on VMIA to process DBI claims in challenging circumstances.

Figure 1: DBI claims lodged each financial year, 2012-13 to 2023-24

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on information from VMIA

Many homeowners were frustrated with VMIA’s handling of their DBI claims and the issue was reported in the media.

In early 2024, one media report quoted a group of homeowners who characterised their experience making a DBI claim as ‘a double catastrophe’. They complained that on top of their home not being finished, they had experienced delays, a lack of transparency and unfair practices from VMIA. We also received a notable increase in complaints about VMIA following the Porter Davis collapse.

Some homeowners raised these issues with their Members of Parliament. On 19 June 2024, the Legislative Council passed a motion requiring the Ombudsman to investigate VMIA’s management of DBI claims. Under our legislation, if either House of Parliament or a Parliamentary Committee refers a matter to us, we are required to investigate and report to Parliament without delay.

The referral raised concerns that VMIA unreasonably refused, reduced or prolonged domestic building claims, promised remedial action but failed to deliver, ignored requests for transparency, breached good faith by under quoting and used non-disparagement agreements to pressure Victorians to settle their claims. The referral was not limited to claims made as a result of the Porter Davis collapse.

Figure 2: Extract of Legislative Council referral letter

Source: Legislative Council

What we investigated

To better understand the issues raised by the referral we asked people who had made DBI claims since 2022 to tell us about their experiences. We received 125 submissions, some of which related to DBI claims made before the Porter Davis collapse and some which related to DBI claims made as a result of it. Of these:

- about 41 per cent came from Porter Davis homeowners

- about 45 different builders were represented

- nearly two thirds related to DBI claims made in 2023.

We also reviewed 260 complaints about VMIA’s handling of DBI insurance we received from 31 March 2023 to 30 June 2024.

The submissions and complaints we received raised some consistent concerns. We focused our investigation on six commonly raised issues:

- Preparedness – Did VMIA take reasonable steps to prepare for a major builder insolvency and the potential associated influx of DBI claims?

- Processes – Were the changes to VMIA’s normal claims management processes adopted after the Porter Davis collapse reasonable, justifiable and in accordance with relevant legislation and policy, and did they impact the integrity of the claim process or outcomes?

- Timeliness – Were there unreasonable delays in VMIA’s management of DBI claims during 2022-23 and 2023-24?

- Communication – Did VMIA adequately communicate with people during the DBI claim process, including reasonably managing people’s expectations?

- Disputes – Was VMIA’s handling of disputes and complaints about DBI claim decisions reasonable, fair and in line with relevant policy and legislation, including the Victorian Model Litigant Guidelines?

- Improvements – Are there improvements that should be made to the way DBI claims are handled (whether by VMIA or a new regulator)?

We also reviewed 46 claim files and identified the same potential issues in some of them. Further information about how we investigated is set out in Appendix 1.

The issue of builders failing to take out DBI for homeowners was considered out of scope, because VMIA was not responsible for this.

In its response to a draft of this report, VMIA said there was a ‘profound selection bias’ in the material we considered, noting it had resolved over 23,600 claims since it started to administer DBI in 2010.

It is likely that many people had a positive experience making a DBI claim, and that those people would be unlikely to contact us. Given VMIA did not conduct claimant satisfaction research, it is not possible to say with any confidence what proportion of homeowners were satisfied or dissatisfied with VMIA’s handling of DBI.

The experiences of the hundreds of frustrated and distressed homeowners who did contact us - even if a small proportion of total claimants - offer important insights into the administration of DBI in Victoria.

VMIA’s approach to DBI

VMIA was established by the Victorian Managed Insurance Authority Act 1996. It provides strategic risk management advice, training and insurance services to government departments and authorities. In 2023-24, it managed $240 billion in funds and paid out $193 million in DBI insurance. DBI was the only insurance product VMIA provided where the beneficiaries of the cover were members of the general public.

Victoria’s building industry is regulated by a number of acts and instruments, including:

- the Building Act 1993

- building and plumbing regulations outlined in the National Construction Code

- the Domestic Building Insurance Ministerial Order.

This ministerial order governs how insurers write DBI policies. Relevantly, the order states that one of its purposes is to specify the:

circumstances in which, and the kinds and amounts of insurance that a builder is required to be covered by before carrying out domestic building work under a major domestic building contract.

VMIA’s DBI policy was shaped by several factors. The policy had to comply with the legal baselines established by the ministerial order. It had to consider commercial insurance principles such as financial sustainability. In addition, VMIA told us it had to act in a market neutral manner, meaning it must not act in a way that would prevent private insurers from re-entering the market.

DBI policies are attached to the property, not to individuals. If a home is sold during the coverage period, the policy continues for the next owner up until the end of the coverage period. DBI covers losses up to the limits in the policy arising from non-completion as well as structural defects (for six years) and non-structural defects (for two years) after completion or after the contract was terminated.

DBI policies allow people to claim up to $300,000. This total covers claims for all defective work, incomplete work and any other losses. Other losses are specific costs created by the home not being finished or by the defect – things like extra rent, storage and temporary fencing for the building site. Some of these are capped, for example, VMIA only covered alternative accommodation for 60 days.

Within the $300,000 limit, coverage for incomplete works is capped at 20 per cent of the original building contract price.

The 20 per cent cap exists because building contracts are paid by homeowners in staged instalments. Therefore, when a builder has died, disappeared, or become insolvent during the building process, the homeowners should have only paid the builder for the completed stages of the build.

Figure 3: Stages of domestic building works

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on information from Consumer Affairs Victoria

Because homeowners pay builders in the stages set out in their contract, they still have the money for the later stages ‘in hand’. This was taken into account by VMIA as DBI will only pay for the additional costs that the homeowner faces if the new builder’s contract for completion is more expensive.

Some VMIA staff described VMIA as a ‘social insurer’. Social insurers are generally government entities that provide financial protection against specific risks, such as workplace injury or transport accidents. In this case, the risk is of a person’s builder becoming insolvent. Social insurers are intended to help people by providing a safety net.

VMIA disagreed with that description, but said that as a statutory government insurance agency, VMIA was required to apply public sector principles to its behaviour, such as good administrative decision making, transparency, responsiveness and respect. VMIA advised that this differs, potentially, from the position a commercial insurer may take, being to achieve the most beneficial financial settlement they can within the terms of their policy. VMIA was required to ensure people making a claim received their full entitlement under the DBI policy in a timely fashion.

However, DBI is an insurance product, rather than a compensation or hardship fund. So VMIA had to operate like an insurer. For example, VMIA staff reference ‘protecting the policy’, which VMIA has described as:

ensuring that, where possible and appropriate, capacity is retained on the policy to allow for future claims within the terms of insurance (up to six years from project completion).

VMIA has advised that:

this principle is particularly relevant in the case of multi-unit developments where the cost of common property defects must be fairly distributed across all the homes in a development which can also greatly increase the complexity of those claims.

Another concern for VMIA was that keeping payouts low supported the overall financial sustainability of the DBI scheme. Considerations like this may create a tension between VMIA’s aims of managing an insurance product and helping people.

However, whether VMIA is a social insurer or simply a statutory one, like other government agencies, VMIA was required to balance the complexity of providing insurance in a way that was both fair and financially viable. This meant exercising discretion within the bounds of the policy to ensure fair treatment and timely outcomes for homeowners, communicating clearly and respectfully with homeowners, and accepting that, as with any government decision, people had a right to complain or seek a review of decisions made under the scheme.

Approaches to DBI across Australia

All Australian states and territories have DBI schemes, although the name for this type of insurance varies. The schemes all have similar aims and most cover major defects for six years. There is variation in how much can be claimed for certain types of defects and overall.

Figure 4: DBI schemes across Australia

Source: Victorian Ombudsman based on DBI legislation and polices across Australia, as at July 2025

Queensland currently has Australia’s only ‘first resort’ DBI scheme, allowing claims even if the builder is still alive and in business. First resort schemes provide more protection and support for homeowners, but are more expensive.

Recent changes to the DBI scheme

After our investigation had begun, the Victorian Government announced changes to the DBI scheme and amended the Building Act 1993.

The biggest change is that the DBI scheme will move from being ‘last resort’ to being ‘first resort’. However, this change will not take effect until 2026. In addition, the DBI threshold will increase. DBI is currently required for building works valued over $16,000. This will be raised to $20,000.

The amended Building Act defines ‘incomplete’ work which was not previously defined in legislation. This is significant because of the 20 per cent cap on incomplete works. In the submissions we received, some homeowners raised concerns around VMIA’s decision to classify some claimed defects as incomplete works.

On 1 July 2025, the Building and Plumbing Commission (‘BPC’) began operations. This new regulator:

- oversees builders and plumbers and the registration, enforcement and discipline activities that were previously the responsibility of the Victorian Building Authority

- provides the dispute resolution services that were previously provided by Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria

- provides DBI, which was previously provided by VMIA.

As the responsibility for DBI claims handling has transferred to BPC, our recommendations for improvements are directed at BPC.

Was VMIA adequately prepared for a ‘large loss event’?

Figure 5: Media reporting on builders collapsing

Source: www.abc.net.au/news, 12 March 2023

VMIA considered any builder collapse that involved 100 or more incomplete homes to be a ‘large loss event’.

Figure 6: Number of builder insolvencies each financial year, 2017-18 to 2023-24

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on information from VMIA

VMIA had dealt with three large loss events before the Porter Davis collapse.

Figure 7: Major builder insolvencies, 2021 - 2023

Builder |

Liquidation date |

Number of claims VMIA received |

Approximate total paid out on claims |

Privium Pty Ltd |

17 November 2021 |

362 |

$7.8 million |

Langford Jones Homes |

30 June 2022 |

186 |

$7.7 million |

Snowdon Developments Pty Ltd |

13 July 2022 |

386 |

$5 million |

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on information from VMIA

During 2022, VMIA was monitoring instability within the building industry. In June, VMIA hired consultants to analyse its outstanding claims liabilities. The consultants noted there was an ‘elevated risk’ of large builders going under in the current environment.

In late August, VMIA’s board heard differing opinions on insolvencies and the economic outlook for the building sector:

- The Housing Industry Association observed that construction company insolvencies were significantly lower than before COVID. It suggested that in 2022-23 builders would ‘whip lash out of cash flow problems’.

- Advisory firm McGrathNicol presented a less optimistic view, suggesting there was ‘increased stress through the building supply chain’. It noted that although insolvencies were lower than previous levels, ‘construction insolvencies as a proportion of all insolvencies increased from 15% in Jan 2018 to 30% in June 2022’.

At this time, VMIA assessed the likelihood of a large builder collapse as ‘possible’. This meant VMIA thought a large loss event may occur within a couple years, but they were not expecting one to occur within months.

VMIA’s preparation for large loss events

VMIA told us that ‘it is challenging to anticipate the likelihood or specific nature of large builder insolvencies’. However, VMIA had ‘taken steps to prepare for insolvency events that exceed its capacity to respond in a timely fashion’.

Large Loss Response Guide

In early 2022, VMIA developed a Large Loss Response Guide which provided guidance and a process for staff to follow for such events.

VMIA described this as an ‘evolving document’. While we agree it is sensible to continually update such a document, what we saw was an unfinished piece of guidance. The document had several sections highlighted and comments noting that more work was needed.

Because this document was always unfinished and intended to continually be updated, we were unable to establish exactly what information it contained before the Porter Davis collapse.

It appears that at that time the guide was largely based on VMIA’s then-recent experiences managing the Privium and Snowdon insolvencies. The guide consisted largely of a table detailing actions to be taken and who was responsible for them. However, there were some gaps, meaning VMIA staff did not have a definitive guide to rely on.

Other guidance materials

VMIA had Claims Handling Guidelines which guided employees through the claim management process, including details about the claim lifecycle, service standards and policy interpretation.

VMIA also had training materials for its online portal specifically for DBI, known as BuildVic.

These documents helped VMIA train new staff at short notice.

Scalable staffing arrangements

VMIA’s DBI team had about 12 full time staff. However, this team relied on a number of external parties. There were building inspectors, two external call centres and a panel of law firms that VMIA used to assist with assessing and managing claims.

VMIA’s arrangements with these external parties were scalable, meaning it could quickly call on more staff to help meet the increased demand for services during large loss events.

VMIA’s awareness of Porter Davis’s situation

While VMIA is not a regulator, it did review a builder’s financial capacity as part of its process for determining the builder’s DBI coverage. VMIA noted this was in line with standard insurance underwriting procedures.

VMIA considered the builder’s:

- financial position

- historical trading performances

- debts and equity

- working capital and funding requirements

- directors and key executives

- reporting and management information systems.

Less complex reviews were conducted by VMIA, but for large builders VMIA appointed an external consultant to conduct an independent assessment.

VMIA could also review a builder’s financial position at any time. The last time VMIA began a review of Porter Davis was in July 2022. This review was completed in November 2022, four months before the collapse. This review found that there were concerns about Porter Davis’s position, but it was ‘moving back towards profitability’.

However, by early 2023, Porter Davis was in serious financial trouble. Porter Davis met with the Victorian Treasurer, looking for a $25 million loan. The Government also talked to the Commonwealth Bank which was Porter Davis’s biggest lender. This was outside of the scope of this investigation, so we did not look into this further.

It appears that VMIA became aware of Porter Davis’s impending collapse in early March 2023.

Figure 8: Timeline of events immediately before Porter Davis’s collapse

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on information from VMIA

On 31 March, the day Porter Davis became insolvent, a senior DBI team member told VMIA’s communications team and the Chief Executive Officer (‘CEO’) that the DBI team had implemented its large loss response plan. They said they had got a list of all building work in progress from Porter Davis and had prepared information for impacted homeowners. It is clear VMIA contacted its external call centre, and that it was aware of the potential exposure, however it is not clear what other preparations or meetings occurred during March 2023.

It is also now clear that the sheer scale of the Porter Davis collapse was unprecedented and VMIA’s team had limited time to prepare as best they could.

Conclusions on VMIA’s preparedness

Did VMIA take reasonable steps to prepare for a major builder insolvency and the potential associated influx of DBI claims?

Before the Porter Davis collapse, VMIA had taken steps to prepare for large loss events. Unfortunately, these preparations were only partly effective.

While VMIA did make updates to its Large Loss Response Guide in late March, the document was still not finalised and contained some gaps. VMIA also scaled up its use of call centre and law firm staff, however these arrangements created some problems. Call centre staff used scripted responses which limited their ability to help homeowners with bespoke questions. Law firm staff, while experienced, were not dedicated claims managers.

Whether VMIA took adequate steps to prepare for the Porter Davis insolvency in particular is a more complicated question. As the insurer, VMIA had monitored Porter Davis in the years before its collapse, including a review of its financial position, completed in November 2022.

One consideration VMIA had was that acting prematurely may have caused Porter Davis reputational damage, worsening its financial position. However, given Porter Davis collapsed just four months later, it seems that the review finding that Porter Davis was ‘moving back towards profitability’ was a significant misjudgement.

By 9 March, VMIA knew that Porter Davis was in talks with the Department of Treasury and Finance (‘DTF’) and that a collapse would result in 1,200 claims, more than three times as many claims as any previous large loss event. By 14 March VMIA was providing advice to DTF on the impacts to VMIA of a collapse. It would therefore be reasonable to expect VMIA to be planning its response at this time.

However, it seems VMIA was waiting to see if the Government would intervene. On 22 March VMIA was told there would be no intervention. At this time, VMIA was in contact with the building company Simonds Homes Victoria Pty Ltd (‘Simonds’) and the possibility of a buyout was still on the table. It appears that VMIA was optimistic that a solution would be found before Porter Davis collapsed.

As well as hoping for the best, VMIA should have started planning for the worst sooner. There is no evidence that VMIA conducted a risk or capacity assessment or developed a plan to minimise the impact on homeowners during March 2023. VMIA did take some steps in the limited time it had available, however, knowing the likely claim numbers, VMIA should have foreseen that its existing plans would not be enough and that it needed to do more to prepare. That said, given the scale of the Porter Davis collapse, and the limitations of preparation for large loss events generally, we do not think a few additional weeks of preparation would have made a material difference in this case.

Was VMIA’s claims process after the collapse of Porter Davis reasonable and fair?

I think the process needs reform … they haven’t started with a process of ‘well how can we help these consumers that have run into problems through no fault of their own because their builder’s died, insolvent or disappeared?’ … the whole approach was adversarial and just the wrong way around … if this process was designed to make people give up, it’s perfectly designed …

– Homeowner

When Porter Davis became insolvent on 31 March 2023, VMIA received a huge volume of DBI claims. In six weeks it got more claims than in the previous financial year.

Figure 9: DBI claims by month, July 2022 to June 2024

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on information from VMIA

To handle the influx of claims, VMIA tried to increase its capacity and streamline its claims process. VMIA’s claims handling process was guided by the ministerial order, VMIA’s DBI policy and its Claims Handling Guidelines.

Figure 10: VMIA’s usual claims process

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on VMIA’s Claims Process Map and DBI Claims Handling Procedure

Throughout this process, a homeowner could deal with several different people at VMIA. AT this time, claims were not assigned to a single claims manager, so a homeowner could speak to a different person at every stage of the process.

Following the Porter Davis collapse, VMIA changed its process:

- In some cases, VMIA based its liability and quantum decisions on a ‘desktop review’.

- VMIA increased its use of law firms to manage claims.

- VMIA entered into agreements with two ‘volume builders’ to quote for work on Porter Davis homes.

Volume builders are large construction companies that build hundreds of homes a year. They are able to build homes cheaper than smaller companies because they buy materials in bulk and use standardised designs.

Response to the Porter Davis collapse

VMIA told us that following the announcement of Porter Davis’s collapse it immediately:

- assessed the potential impact and planned the initial claims response

- activated its large loss response plan and established a dedicated Porter Davis response team

- set up a response team room, daily Porter Davis information sharing sessions, daily reporting and other arrangements to track developments

- started planning to boost DBI team resources

- contacted key stakeholders across government to coordinate responses and communication, including DTF, the Assistant Treasurer’s office, the Victorian Building Authority and Consumer Affairs Victoria.

In the weeks and months following the collapse, VMIA:

- established a dedicated phone number and email address

- activated, briefed and trained external call centre staff

- established a dedicated Porter Davis page on its website and a dedicated Facebook group

- delivered seven information sessions to Porter Davis homeowners

- engaged:

- three law firms to help assess and manage claims

- former Porter Davis employees with ‘deep knowledge of existing defect issues’ to help with defect claims for occupied homes

- two external providers to do building inspections

- media and communications experts to supplement its internal team.

VMIA also received detailed information about all incomplete and defective building projects from Porter Davis’s liquidator, Grant Thornton. This was intended to streamline initial claims assessments, make it easier for builders to quote and save time and costs on claim assessment.

Liability decisions

VMIA took steps to streamline its liability decision process where it could. It:

- used aerial photography to confirm building works had not started where homeowners were claiming back their deposit only

- engaged the building surveyors originally responsible for signing off the building work on Porter Davis sites to help substantiate incomplete works claims

- sometimes undertook ‘desktop reviews’ to make liability decisions on claims of incomplete works instead of sending an inspector out to the property. This was done where VMIA had ‘sufficient information’ from the liquidator and quoting builders to decide without a site visit.

VMIA acknowledged that this was ‘bypassing normal verification processes’ but is confident that these process changes did not compromise liability decisions.

While these process changes appear to be reasonable, they are not without risk. In some cases an assessment is simple and a desktop review may be appropriate (for example, where only the slab of a home had been laid and it is agreed there are no defects). However, in complicated cases a desktop review may not always be sufficient.

Another issue with liability decisions was the lack of detail in inspection reports. The files we reviewed showed a decrease in the detail and reasons given which raised transparency concerns for some homeowners.

Defects or incomplete works

Some homeowners told us they didn’t understand VMIA’s classification of items as being defects or incomplete works.

When lodging a DBI claim on an incomplete home, the homeowner should list each individual item they consider is a defect in addition to identifying that the building is incomplete. Inspection reports then recommend which items should be accepted and whether the items are defects or incomplete works. These reports should also provide reasons for their recommendations but did not always.

While VMIA considered inspection reports when making liability decisions, it was ultimately VMIA that determined which items were defects and which were incomplete works.

VMIA considered any item that would be fixed by a builder in the ordinary course of completing the build to be an ‘incomplete work’. VMIA gave this example:

A bathroom which is complete with the exception of fittings such as towel rails, mirrors etc.

- A homeowner may perceive this as a defect, not being in line with the specification in the contract and clearly not fit for purpose

- This would be incomplete works as the works had not previously been undertaken and a builder in completing the works would complete the installation to the standard specified.

When asked how VMIA determined what would be fixed in the ordinary course of building, VMIA said it relied on prior experience and advice from builders. VMIA said it ensured consistency in decision making through:

- the application of the ministerial order

- the application of the DBI policy

- the application of the Claims Handling Guidelines

- the building inspection and other expert reports

- discussions and meetings with team members.

Given the ministerial order, policy and claims handling guidelines did not define incomplete works, it is unclear how these documents assisted VMIA in making consistent determinations. At times VMIA’s decision would differ from that of the inspectors. Its decisions could not be easily documented in the file and clearly communicated to a homeowner, giving them little confidence that the decision was made fairly.

This is notable because claims for incomplete works are capped at 20 per cent of the original contract value. Claims for defective work are limited only by the $300,000 total policy cap. When VMIA reclassified as incomplete works items the homeowners considered defects, some homeowners felt VMIA was unfairly trying to reduce the payout. Some submissions we received speculated that this approach was taken to minimise costs.

The inspection reports relied on by VMIA and subsequent decisions could, at times, appear to contradict the findings of inspections that the homeowners had commissioned. This caused extra stress and concern for some homeowners.

Resolving a disagreement about a classification was difficult because there was no definition for ‘incomplete works’ in legislation, the DBI ministerial order or in VMIA’s policies. Defects are defined in the Domestic Building Contracts Act 1995 and this definition is reflected in the ministerial order and VMIA’s DBI policy. This gap has been recognised and the new Building Legislation Amendment (Buyer Protections) Act 2025 includes a definition for incomplete works.

Clarity of liability decisions

The claim files we reviewed showed that:

- there was often no internal VMIA record of reasoning for decisions

- there was generally no reasoning provided to homeowners

- VMIA occasionally reclassified items as incomplete works that had been classified as defects by building inspectors.

Similar concerns were observed in the decision letters issued at the quantum decision stage of the claims process.

Homeowners were informed about VMIA’s liability decision through an outcome letter with an attached Schedule of Works. However, these often contained no explanation about why items claimed as defects were reclassified as incomplete works.

Figure 11: Example of information in Schedule of Works

Source: VMIA

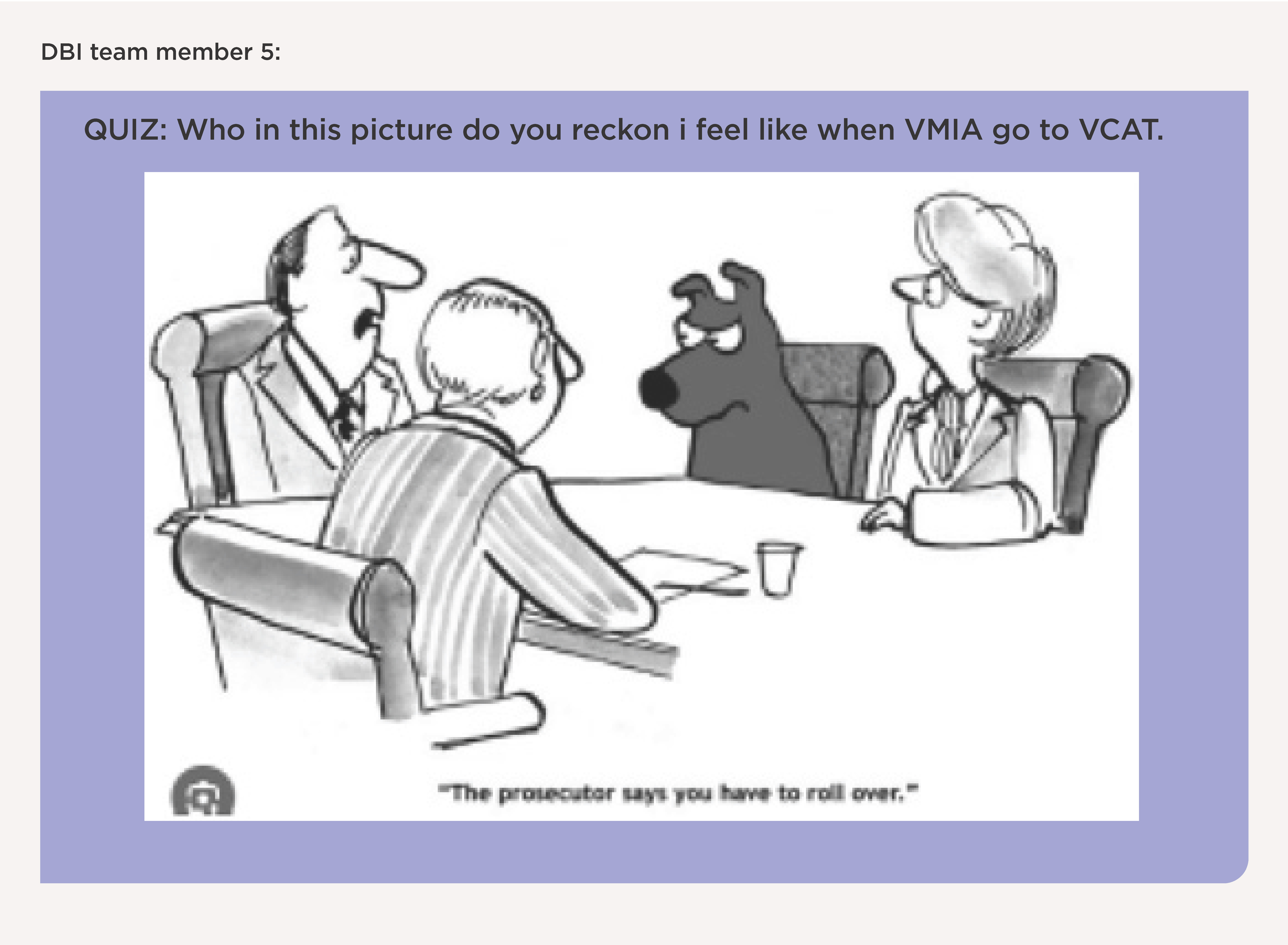

This lack of transparency also created an issue when homeowners wanted to dispute VMIA’s decisions. Without documented reasons it was not possible for a homeowner to determine whether VMIA’s decision was reasonable and therefore whether they should pursue the matter further. This put the homeowner at a disadvantage if they decided to challenge VMIA’s decision at the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (‘VCAT’).

Concerningly, we also saw instances where VMIA reclassified items with the acknowledgement that the decision may need to be changed if the homeowner disputed it. One claim file had a note saying:

… VMIA changed [the law firm’s] draft to include items 2, 3, 5, 25, 28, 37, 39, 42, 43, 47, 48 as incomplete work, although there is a very strong possibility that the VMIA would need to accept those works as defective work, in accordance with [the law firm’s] advice, if dispute was raised. The position may need to be revisited.

There were also instances of inconsistency in VMIA’s decisions about adding items to claims. In some instances, homeowners were directed to lodge a new claim and reference their existing one. In others, homeowners were told to add items to their existing claim.

Additions to existing claims had to be made 48 hours before the inspection. However, we saw an instance where VMIA rejected items on the basis that they were added too close to the inspection time, even though they were outside the 48-hour cut off.

VMIA disagreed that there was material disadvantages to homeowners through this process and said:

Homeowners can lodge as many claims as they need as defects arise. Allowing additional items to be added to an existing claim may be an effective measure in some circumstances and not in others.

This is in fact beneficial to the policy holder.

These sorts of inconsistencies and the general lack of transparency around decision making led some homeowners who contacted us to distrust VMIA and conclude that its decisions were not fair or reasonable.

Panel law firms

Figure 12: Media reporting on VMIA’s handling of DBI claims

Source: www.abc.net.au/news, 17 June 2024

… the involvement of a law firm is just the wrong way. The law firm should be providing legal advice on legal issues … and the VMIA should appoint a claims manager … they are trained and deal in … managing a claim, getting to the root, … cause of what actually is the problem … Law firms just aren’t equipped to do that. They’re equipped to fight claims. And to be difficult … Law firms are just not the right people to manage claims.

Homeowner

VMIA had an ongoing relationship with a number of law firms. Before the Porter Davis collapse, these firms:

- provided advice and representation for matters being challenged at VCAT

- drafted decision letters

- managed complex matters

- managed matters relating to specific insolvencies.

To handle the influx of claims after the Porter Davis collapse, VMIA scaled up its arrangements with its panel of law firms to boost its capacity:

- VMIA temporarily engaged graduate lawyers and paralegals from its panel law firms.

- VMIA referred specific matters to its panel law firms for management.

VMIA told us that it considered alternative options, such as traditional recruitment or temporary staffing, but that these would not have provided the same rapid upscaling and would have drawn resources from the immediate claims response. VMIA said that law firm staff were already familiar with VMIA’s DBI policy and were able to contribute effectively with basic training on the BuildVic system.

VMIA's position was that the ‘optimum way to respond to the greatest number of homeowner claims in the fastest time possible was to augment VMIA internal resources via engagement with existing panel law firms’.

VMIA advised that:

panel legal firms were mainly tasked with specific elements of the claims assessment process … All actions by legal panel firms were under instruction from VMIA with decisions approved by VMIA staff with delegated authority.

Scope of law firms’ involvement

VMIA used law firms to both complete specific tasks on claims and to manage stages of claim files.

In our review of limited claims files, what we saw was that generally speaking, law firms received individual instructions from VMIA in relation to their actions and decisions. The process for issuing and following instructions did not always run smoothly. At times, this created tension between the law firms and VMIA. A senior DBI team member wrote to a law firm:

I cannot keep giving the same instructions to people. Seriously, I do not have the time. I just need these decisions issued, particularly if I have given instructions already … I allocated the easy files … I really didn’t think there would be this many ongoing queries. If we cannot get at least 40 decisions from you guys in a day, I really need to move these files elsewhere, because I have deliverables to meet on a daily basis

Similarly, VMIA claims handlers were frustrated:

I love it how I am getting referred back to a file that we have briefed out? [Are they] billing us to write to me to get me to do [their] work?

And on the other side, law firms were frustrated when VMIA provided delayed instructions:

We have been persistently seeking instructions since 1 May 2023 … We received those instructions on 1 August 2023 (a period of 3 months).

There were also instances where it was not clear who was responsible for managing a claim and the claim was left unattended. This appears to have happened because there was confusion about whether law firms were managing a stage of the claim or just undertaking specific actions, such as drafting an outcome letter. A claim would appear to be allocated to a law firm in the BuildVic system, but they may have only been doing a specific task. These cases were only identified when homeowners complained about the delay.

The involvement of law firms, and the reasons for it, were not adequately communicated to homeowners.

At times, the first communication homeowners would receive, after an automated acknowledgement from BuildVic, came from a law firm advising that it was acting on behalf of VMIA.

Figure 13: Excerpt of letter from law firm to homeowner

Source: VMIA claim file

While there is nothing inappropriate in this letter, some homeowners could have found it confusing or intimidating to be contacted by lawyers, especially where they had not been contacted first by VMIA.

It could also be difficult for homeowners to know who they were really dealing with as law firm staff would engage in different ways. Sometimes they used VMIA’s generic DBI email address, other times they used their legal firm’s letter head.

Some homeowners found that the involvement of law firms was the key to getting their claims progressed. Others who made submissions told us they found communications from law firms quite confronting. One homeowner whose case was passed from VMIA to a law firm with no warning wrote:

I received an email from individuals I had never heard of, claiming to represent VMIA, and instructing that all future communication had to go through them. I thought it was a scam. When I asked for proof of their legitimacy, I was told I was not entitled to it and should simply trust that they were acting on behalf of VMIA. I tried contacting the VMIA to verify … and eventually just gave up and trusted a stranger that emailed me randomly that they represented the VMIA because this was how the process worked, apparently.

Another homeowner wrote:

The VMIA is spending money on lawyers that aren’t required. I had not threatened any legal action, yet got a letter without warning saying that the VMIA had engaged lawyers to deal with my case. This is combative and not helping solve the problem. Not to mention a massive waste of money that isn’t required if they followed their processes consistently.

VMIA acknowledged that it could have done better in overseeing how its panel lawyers framed their communication with homeowners. Lawyers often write as though the matter is the subject of litigation or dispute. VMIA advised that the use of such legal language in ordinary communications with homeowners about their claims would be inappropriate.

Even before the Porter Davis collapse, VMIA was aware of how communications could be received and tried to improve them. When one law firm asked for a draft to be reviewed, a senior DBI team member wrote:

Whilst your letter was an excellent response from a litigator, as a public sector entity we always have to be mindful that any response prepared by us or on our behalf could potentially end up as a complaint to the Minister’s Office. I therefore like to make sure our response is self explanatory enough to show that we were acting reasonably if anybody was ever provided with it.

We agree that, as a public service entity, VMIA should have communicated clearly and transparently in a way that homeowners could understand. As case study 1 shows, the involvement of lawyers could make the process more adversarial.

Case study 1: VMIA’s lawyers take an adversarial approach to claims management |

In 2020, Delco Building Group built nine townhouses in inner-north Melbourne and sold them all by late 2021. The owners identified a range of problems after moving in, some to do with plumbing and waterproofing. Delco began repairs, but on 1 February 2023, it became insolvent. Two weeks later, one of the townhouse owners, Steve Robinson, made a DBI claim for items at both his unit, and common property. As the Chair of the Owners Corporation, Steve also co-ordinated the claims on behalf of the other owners and one claim for the common property. Altogether the owners identified over 170 defects and other items. Some of these were duplicates across individual homeowner claims and the Owners Corporation claim. Steve liaised with VMIA and the panel law firm they assigned to the claims. Steve was a lawyer himself, which meant he was in a better position than most people to understand and challenge, where necessary, the legal correspondence from VMIA’s lawyers. In March 2023, VMIA’s appointed inspector attended Steve’s townhouse. They recommended that VMIA accept liability for five of the 18 defects Steve had claimed for. Steve also arranged an independent building inspection of the whole property in March. The claims became very complex. The VMIA lawyers informed the nine owners they could make new claims for the additional defects. In order to lodge a claim for the common property defects, the two Owners Corporation representatives, of which Steve was one, needed to make a separate claim. There were 19 separate claim files in total, each with a $500 excess. This resulted in 49 decision letters being issued over a 16-month period from the first lodged claim as decisions were amended and superseded. VMIA told us that ‘while the circumstances of a multiunit development are always complex, the items contained in the claim were, for the most part, straightforward’. Some items were denied on the basis that they were addressed in another claim, arose outside the coverage period, or there was no evidence of a defect at inspection. In early May, the lawyers provided VMIA with detailed advice on Steve’s claim. Being lawyers, they approached the claim in an adversarial manner. They recommended denying some items ‘at the first instance’ on the basis that the policy may allow for the rejection, despite the inspection recommending those items should be accepted. They advised VMIA to ‘review this position if the Claimant disputes the denial’. This approach does not appear fair from a statutory insurer who could have taken a more beneficial view while remaining within the terms of the policy. One week after giving that advice, the lawyers issued a formal VMIA liability decision accepting two items in line with their advice. This was 87 days after Steve made his claim. Steve was unsatisfied with the decision and disputed some of the denied items. It took several months to resolve this dispute with Steve and the lawyers going back and forth. Steve told us he tried repeatedly to arrange a meeting with the lawyers to discuss the claims and met them on at least two occasions. However, other times Steve said the lawyers refused to meet and their ‘whole approach was adversarial’. Liability decisions for the second round of claims were issued on 25 August, then revised on 22 December. These last decisions were sent out on a late Friday afternoon, three days before Christmas. Steve was concerned these letters contained errors and he considered taking the matter to VCAT. VCAT appeals must be lodged within 28 days of the decision being made. However, acknowledging the holiday period, the law firm told Steve VMIA agreed not to oppose any application he lodged outside of the 28 days, if he did so before 16 February 2024. Steve told us he contacted the law firm but he did not receive a response until late January 2024. He asked whether going to VCAT would delay the whole process, or whether VMIA would pay the agreed items. The lawyers advised VMIA that ‘… it may put the claimant off appealing if VMIA halts the claim pending the outcome of the appeal. The claimant is difficult and a former solicitor. We recommend proceeding with quantification and settlement of the accepted items.’ This was on 1 March 2024, more than a year after Steve first made his claim. VMIA decided to pay out the accepted defects and got quotes from three builders for the accepted items for all nine townhouses and common property. In April 2024, the lawyers advised VMIA to go with the ‘most competitive’ quote and sent Steve the quantum decision. This was revised in June as it did not originally include the right number of toilets, and Steve was able to add an item to his claim for alternative accommodation. The lawyers revised the settlement terms for all the owners affected. On 9 September 2024, 19 months after making his claim, Steve accepted a settlement of $26,390 for his individual unit. Each homeowner also received $881 from the Owners Corporation claim for common property. For some of the other townhouse owners, Steve told us the matter dragged on even longer. He said that more than two years after the claims were made, the repairs were still not complete and some waterproofing defects have since been found to be more extensive than originally identified. We understand variations to the initial claims for additional works for these defects have been accepted and are currently being addressed. Speaking on their experience with the new BPC, the homeowners said they have found it to be ‘more customer focused, helpful and responsive’. |

The DBI team explained that the timeframes Steve experienced were typical of multi-unit claims that involve multiple homeowners. Identifying the root causes of issues, and coordinating repairs, is more complex for such claims than for single dwellings.

Cost of law firms

VMIA needs to stop external law firms being de facto claims handlers. Turns it into an adversarial process and must be costing a proverbial ‘bomb’ in fees.

– Homeowner

While using law firms did increase VMIA’s capacity to manage claims, it also carried a significant financial cost.

Figure 14: VMIA’s expenditure on law firms for DBI, 2022 to 2024

Year |

Law Firm A |

Law Firm B |

Law Firm C |

Law Firm D |

Total |

2022 |

$14,830 |

$1,050,510 |

$84,730 |

$3,006,930 |

$4,156,980 |

2023 |

$21,200 |

$1,248,360 |

$861,260 |

$5,204,140 |

$7,334,960 |

2024 |

$18,750 |

$1,631,290 |

$2,686,310 |

$7,018,490 |

$11,354,850 |

Total |

$54,780 |

$3,930,160 |

$3,632,300 |

$15,229,560 |

$22,846,790 |

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on information from VMIA

Some VMIA staff questioned the value of the lawyers:

DBI team member: we should get rid of some of these grads because they are just not listening …

Senior DBI team member: Tell me who you don't need and is a liability

DBI team member: Most of them. They just don’t care and think its beneath them. We are wasting money

Senior DBI team member: That's OK. They cost us a lot of money and if there is no value, we are better off getting one competent additional resource or two.

DBI team member: Just pay me what you pay them and I’ll do it lol

The use of lawyers to manage claims and the associated expense could lead some homeowners to question the fairness of their insurance outcome where they were dissatisfied due to a perceived imbalance of power.

While spending large amounts on lawyers may seem manifestly unfair to homeowners, VMIA executives considered this was required to avoid extended delays.

Quantum decisions and volume builders

Our quantum decision took a long time … the amount is underquoted … We think that they didn't even read what we have submitted. We felt like they have already made up their mind on which builder's quote they will take … we just want to finish our home and go back home.

– Homeowner

VMIA made other changes to its process including:

- VMIA stopped sending builders quotes to the original building inspector to assess

- VMIA entered into agreements with two volume builders giving them the opportunity to provide quotes for most of the incomplete Porter Davis homes.

After a liability decision had been made and builders had quoted on the job, VMIA’s usual process was to refer the quotes to the original building inspector to confirm they met the Schedule of Works. The inspector could also express a view on relevant elements of any quote for consideration as part of VMIA’s assessment of the quantum decision.

Builders quotes were assessed against four criteria:

- The quote had to comply with the approved Schedule of Works.

- The builder had to have the capacity to undertake work to the appropriate standard.

- The builder had to have the capacity to start and complete the works in a reasonable timeframe.

- Price could be considered where there were multiple quotes.

A quote had to meet all criteria to be chosen as the basis for a quantum decision. Once a preferred quote was chosen, a VMIA staff member would make a quantum decision and issue a decision letter to the homeowner. This staff member needed the appropriate financial delegation, meaning they had to have the authority to commit VMIA funds to that value.

The quantum decision letter offered the homeowner a settlement amount based on the chosen builder’s quote and the price of the original building contract. The homeowner could accept the quantum decision or seek a review.

Homeowners could choose to use a different builder to the one VMIA based its quantum decision on, however this would not change the decision. VMIA would only pay out the amount it calculated based on its chosen quote. If homeowners wanted to use a more expensive builder, they would have to pay the difference themselves.

Referral of quotes to original inspectors for validation

Having the original building inspector review the quotes served two main purposes:

- It ensured the proposed works would be sufficient to address all the defects and incomplete works that VMIA accepted liability for.

- It minimised the risk that a builder would not complete the works to a satisfactory standard.

However, instead of referring quotes to the original building inspector, VMIA relied on its internal staff to undertake this review. VMIA told us that the former Porter Davis staff it had hired provided it with the technical expertise to assess quotes.

In some cases, VMIA assessed and approved quotes in batches. This involved VMIA staff working in a group to evaluate quotes against the four criteria and presenting them to someone with the appropriate financial delegation. VMIA said this ensured that assessments were efficient, consistent, valid and fair.

VMIA’s view was that this process worked particularly well. While the decisions were recorded in the BuildVic system, as would be the case in a standard assessment process, we did not identify detailed records of these meetings.

Engaging volume builders

In response to the Porter Davis collapse, VMIA did something it had never done before. It partnered with two volume builders that were comparable in scale to Porter Davis. On 28 July 2023, after several months of negotiation, VMIA entered into ‘Opportunity Agreements’ with Simonds and Metricon Homes Pty Ltd (‘Metricon’).

Figure 15: The volume builders VMIA partnered with

Source: www.simonds.com.au and www.metricon.com.au

VMIA chose these builders as they had the ‘infrastructure and capacity to complete an unprecedented number of homes for impacted homeowners within reasonable timeframes’.

VMIA told us that volume builders could ‘quote multiple projects simultaneously’ and with ‘similar volume-based pricing structures’ to Porter Davis. By partnering with Simonds and Metricon, VMIA intended for homeowners to minimise any out-of-pocket losses they may have had by engaging another builder.

VMIA’s view was that volume builders could bring capacity and efficiencies to the work and this would lead to a better outcome in terms of cost and policy coverage for some homeowners, and a faster project start and finish.

VMIA was confident that the scale and experience of the volume builders meant homeowners could be assured that the quality of the work would match what Porter Davis would have provided. However, VMIA did not assure homeowners about the volume builders’ capability to perform the work.

Simonds and Metricon were provided with high-level claims information for about 300 Porter Davis builds. The volume builders could then use this information to conduct either a desktop review or an onsite inspection.

VMIA told us that it was acting as a prudent insurer in using this strategy to get the best value for money, as doing so protected the total cap on the policy. This meant that the owner, or subsequent owner, could make an additional DBI claim if they needed to. VMIA observed that it would only worsen the situation for the homeowner if the cap was exhausted. In addition, keeping claim costs as low as possible helps keep the cost of the DBI policy down.

The Opportunity Agreements did not oblige VMIA to award the volume builders the Porter Davis contracts and were clear that the homeowner kept the option to choose a builder.

However, VMIA was required to provide the volume builders with a reason if their quote was unsuccessful and to allow them to requote on the relevant properties. In an email from VMIA issuing instructions to a panel law firm, a senior DBI team member noted:

Where a Metricon quote is more than the owner’s quotes, please refer the matter back to us via email and we will invite them to revisit their quote within an expedited timeframe.

It is not clear whether the option to requote was presented to other builders.

The volume builders could charge VMIA a set fee for their quote if they ultimately did not proceed as the chosen builder.

VMIA told us that while it was not in the written agreements, there was a verbal understanding with the volume builders that there would be ‘smoothing’ of quotes to ensure as many as possible came in under the 20 per cent cap. It was VMIA’s understanding that if the volume builders were given a large number of properties to quote on, they would underquote on some, and overquote on others to get as many through under the 20 per cent cap as possible.

While smoothing can benefit the DBI scheme overall, it is not always fair to individual homeowners. If a homeowner was overquoted because of ‘smoothing’, they would have less of their $300,000 cap left to claim against, should any defects arise in the future. However, other owners benefited, and we accept VMIA was trying to maximise the benefit of the DBI policies for homeowners as a whole. We also acknowledge that the ‘smoothing’ may not have had any practical implication for most homeowners who would primarily be concerned with getting their house built within policy caps.

The practice of smoothing was never communicated publicly, meaning homeowners whose quotes were affected by this approach had no idea.

After entering into the Opportunity Agreements, VMIA monitored the volume builders. VMIA engaged an external advisory consultant to ensure the volume builders were viable and could handle the extra work.

The Opportunity Agreement also allowed for VMIA to audit both volume builders’ records to ensure they met their obligations, and set out regular reporting requirements and a dispute resolution mechanism.

Volume builders quotes

VMIA obtained its own quotes from its preferred builders, in addition to those submitted by homeowners, because it had a responsibility to ensure value-for-money outcomes.

The volume builder quotes were often notably lower than the next nearest quote. Given volume builders can generally deliver builds for less, this was to be expected. In fact, this was one of the reasons why VMIA entered these agreements.

In response to a draft of this report VMIA noted that for:

the purpose of assessing a homeowners loss, price variations between quotes are irrelevant as long as they comply with the specification and the builder can be held to the works in a reasonable timeframe at the quoted price under a domestic building contract.

VMIA was satisfied that the builders were prepared to complete the project to the appropriate standard and specification at the quoted price.

However, in some cases, the variation between the volume builder’s quote and the rest of the quotes was so significant it is unclear how it was considered reasonable. Some homeowners described some volume builder quotes as a ‘low ball quote’, a ‘highly questionable underquote’ and ‘an absolute joke'.

We understand why some homeowners felt this way when they received a lower quote that was often just one line without details. By contrast, homeowners were told that any quote they obtained needed to contain details of the works and it was VMIA’s preference that all defects be itemised.

VMIA advised that it could rely on the established relationship with the volume builders to be confident the quote would deliver to the original specification. However, homeowner sourced quotes needed to be in sufficient detail so that VMIA could be confident that the works would fully resolve all the items in the Schedule of Works. This, however, does not appear to have been immediately clear to the homeowner receiving the one-line quote.

Sometimes VMIA only got one quote. VMIA told us that following the Porter Davis collapse, the availability of builders comparable to Porter Davis was significantly limited. This meant seeking multiple quotes was not always possible and could have created further delays.

VMIA took the view that one quote was sufficient in some cases, dependent on:

- the nature of the incomplete and defective works

- the high volume of quotes for similar claims which provided a reliable reference point for necessary works and appropriate pricing

- the capability and capacity of the builder being asked to quote.

- Submissions from some homeowners expressed frustration that their quotes were not used by VMIA, which relied on the volume builder quotes.

VMIA was aware that some homeowners felt the volume builder quotes were unreasonable. One email from a senior DBI team member to a panel law firm said:

I am keen to ensure we develop wording for application to similar circumstances as this places us in the best position to counter claims from others to say that the quote is not real. Simonds are indeed keen for this project so it can be done for the amount quoted.

The reality was that where a volume builder’s quote was the cheapest, and they could deliver the works to the required standard and specification within a reasonable timeframe, VMIA would rely on it to make a quantum decision. Also, as the volume builders were given the opportunity to requote if VMIA was considering going with an alternative, they were more often than not the cheapest and therefore successful quote.

A cheap quote was a good outcome for VMIA, who were concerned with keeping costs down and protecting the policy cap for six years. It was also a good outcome for many homeowners who were able to complete their builds without being further out of pocket.

However, where homeowners chose to use a different builder, they were often unsatisfied with VMIA’s quantum decision based on a volume builder quote. VMIA should have communicated better with homeowners about its arrangements or planned arrangements with the volume builders to better manage expectations.

Case study 2 shows how the process of reaching a quantum decision was not always straightforward for complex claims, particularly where VMIA relied on a quote that the homeowners felt was an underquote.

| Case study 2: VMIA struggles to resolve a complicated quantum decision |

|---|

Matthew and Sarah Nguyen began building their Warranwood home with Porter Davis in February 2022. When Porter Davis collapsed, their house was incomplete. They made a DBI claim on 2 April 2023 and very quickly organised an inspection to determine incomplete works and defects. The Nguyens wanted to keep their build moving as they were paying rent as well as their mortgage and could not afford to continue paying both. They decided to take on the role of owner-builders so they could manage the remaining works themselves and took photos of the defects before beginning work. They told VMIA they were continuing as owner-builders on 1 May 2023, and tried to make sure VMIA had all the information it needed before they started works. On 2 June, VMIA sent out an inspector. The report said that the majority of the defects had already been fixed. VMIA made a liability decision on 26 June. In August, five months after making their claim, the Nguyens finished building their home, but they were still awaiting a quantum decision. They told VMIA that ‘[t]he length of time to process our claim is excessive and the lack of communication is unconscionable’. On 6 September, VMIA replied, asking them to supply invoices and receipts for the defective items that they had already fixed so it could make the quantum decision. The Nguyens told us this requirement had not been mentioned before. The Nguyens went back and forth with VMIA over this issue several times. It was not simple for them to provide this documentation. In some cases they had paid cash to keep their costs down and had no receipts. In other cases the defective works were repaired alongside new works, like fixing water damaged plaster while the remaining plastering was done, so separate invoices could not be provided. The Nguyens provided a breakdown of all their costs and outstanding defects to be rectified on 5 October. VMIA sought a quote from Builder A, a builder that specialises in completing building works where the original builder cannot. On 13 October, Builder A provided its quote, however, it contained photos of the wrong house and the Nguyens thought the quote was unrealistically low. VMIA also got a quote from Simonds. In the same month, the Nguyens were told all correspondence should go through VMIA’s panel law firm. Four and half months after making the liability decision, VMIA made a quantum decision for $169,020. This was the first of three quantum decisions. This one was based on the Builder A quote – the lowest total by over $86,000. The Nguyens queried this decision, saying they had spent $373,030 rectifying items. Builder A requoted on 20 November, with the total costs quoted at $440,355. VMIA used this new quote to make its second quantum decision for $252,620. VMIA told the Nguyens they could accept the decision, or could seek a review at VCAT. The Nguyens emailed VMIA seeking a review of the decision. They wrote: … the quantum decision issued on 17/11/23 was based on the assumption that we’d completed all of the defective works whereas the quantum decision on 01/12/23 was on the assumption we’d completed none of the defective works. I wanted to understand how these assumptions had been made? … VMIA did an internal review and made another quantum decision on 24 January 2024, which superseded the previous one. This decision related to incomplete works and alternative accommodation. The decision noted: you will provide us with a breakdown of costs incurred, by way of invoices and receipts … VMIA will review the costs incurred and issue a further quantum decision. The Nguyens provided their receipts but felt they were being treated unfairly as they knew other owner-builders in similar situations had not been asked for this evidence. They accepted this offer for the incomplete works, but the decision regarding defects was not resolved. In April 2024, over a year after they had made their claim, the Nguyens spoke to the media about their experience with VMIA. In late May, VMIA wanted to visit the Nguyens’ house with Builder A to see what defects still needed fixing to help them decide what more they would pay. The Nguyens were frustrated by this, noting: [Builder A] has already undertaken this assessment and quoted the figure $158,925. This figure … was approved by the VMIA and … we confirmed our acceptance … we are simply awaiting payment of the agreed amount and fail to understand the reason for this ongoing and distressing delay. VMIA said the inspection was necessary: In circumstances where you cannot produce evidence of the costs incurred … we would be legitimately entitled to reject your claim for those defects … The inspection occurred and Builder A provided a new quote, but the Nguyens were still concerned about being underquoted. VMIA offered to pay the Nguyens $130,810, which was less than Builder A had quoted the year before because the value of defects was assessed in a different way. In July 2024, a year and three months after making their claim, the Nguyens accepted this settlement. The Nguyens told us they were not happy with this amount but felt unable to continue to fight the matter. |

The DBI team noted that VMIA was required to administer public funds responsibly and asked for receipts for this reason. The DBI team said:

This is standard practice across industry and government to minimise tax evasion and fraud fostered by a cash based economy.

The DBI team noted that:

VMIA provided the [Nguyens] with an offer some six months before their claim was finally resolved, which would have been more favourable to them if accepted at the relevant time. Instead, the [Nguyens] opted to challenge the VMIA’s quantum decision, resulting in the parties agreeing on a methodology for assessing the value of their defect claim which ultimately resulted in an outcome less favourable to them in monetary terms.

Impact of the Porter Davis collapse on VMIA staff

Figure 16: VMIA staff conversation, 31 March 2023

Source: VMIA Teams chats

The claims flowing from the Porter Davis collapse had a significant impact on staff welfare. VMIA staff were dealing with high workloads and high expectations while responding to people making claims who were also in a highly stressed situation, dealing with financial, personal and relationship hardships.

Workload pressures

He said COB today but we don't have COB

– DBI team member

Would like to take tomorrow off.’ Written on a Saturday

– DBI team member

im logging off in a minute, havent fucken stopped, eyes gone blurry

– DBI team member

The DBI team had about 12 claims handlers reporting to one Manager who reported to the Head of DBI. This structure created the potential to delay the progress of high value claims, especially during large loss events, as only a small number had the financial delegation to approve decisions to pay out more than $150,000.

Regardless of their delegation, all staff were working very long hours. DBI team members were asking each other for help with their workloads:

if I am desperate … are you free/around this weekend to jump on for a few hours?

…

I am hoping to not work saturday. I would like to have a day off at some point lol

i think im up to like day 26 or something obscene

The allocation of claims to DBI team members was also a source of frustration for staff. A portion of the team worked on Porter Davis claims only, with the remaining team members assigned any other claims.

In correspondence we reviewed, there did not appear to be much opportunity for staff to move between claim types.

Expectations were not always clear. Staff were trying to process as many claims as possible, but when one DBI team member allocated to Porter Davis helped another staff member with non-Porter Davis claims, senior staff questioned why they did so.

DBI team members were frustrated with senior staff contradicting themselves, one saying ‘This whole thing has been so confusing’.

Expectations and targets

Amid an increasing volume of Porter Davis claims, senior management set targets for staff to ensure liability decisions were issued within 90 days.

A senior DBI team member told staff:

hitting the daily target number is mandatory and non-negotiable … I know it is a bit of a challenge, but I am confident we can deliver if we work as a team.

The first target for Porter Davis claims was set in April 2023. Staff had to make two liability decisions per person per day, or 50 per week for the whole team of five. Based on statistics for the last week of April, this target was not being met.

By the beginning of May 2023, the target increased to 50 decisions per day or 250 per week. Individual case allocations varied from 5-10 decisions daily, while some panel law firms were given as many as 50 to complete in a day.

Targets also fluctuated multiple times during the same week.

Figure 17: Target tracking dashboard

Source: VMIA