When the water rises: Flood risk at two housing estates

Date posted:

Summary

As we now have the threat of a flood hanging over us forever, we would love to sell and move out. But who would buy our property and at what price?

Resident

What we investigated

The Legislative Council required the Ombudsman to investigate flood planning decisions for two housing developments in inner-Melbourne, beside the Maribyrnong River:

- Rivervue Retirement Village (‘Rivervue’)

- Kensington Banks.

Rivervue unexpectedly flooded, badly damaging 45 homes, when the Maribyrnong River burst its banks in October 2022. Homes at Kensington Banks did not flood, but modelling done since shows about 850 are at risk of future flooding.

The Legislative Council required us to look at past and current flood models for the Maribyrnong catchment, and planning decisions for both developments. We were also asked to consider potential policy changes, and whether affected residents should receive compensation or other support.

Why it matters

Though built at different times and with different levels of government involvement, Rivervue and Kensington Banks have much in common. Both involved flood protection works promising to protect homes; and yet both are now considered flood prone.

Together, they tell a broader story about how flood risk is assessed and managed in Victoria, and highlight serious gaps in existing systems.

These have implications for people across the state. Victoria’s Climate Science Report 2024 predicts that, based on current trends, flood risk will double by 2100. Climate change, urban creep, and housing pressures, among other things, mean the way we all live with flood risk must evolve.

What we found

In relation to Rivervue:

- Two early design problems explain the flooding at Rivervue. Melbourne Water’s rushed and flawed flood modelling used during early site development underpredicted flooding. This meant homes were set too low from the start. Mistakes in approved building plans saw some homes built lower still, without a full safety buffer.

- The removal of a key flood planning control had no impact on home design. The two problems existed well before a flood overlay was lifted from Rivervue in late 2016. Looking back now, the removal decision was clearly incorrect. It was understandable though, as Melbourne Water gave advice – based on its flawed modelling – that protective works had effectively lifted homes from the floodplain. We found no evidence of improper influence.

- Vulnerable retirees are left living in a known flood hazard area. Melbourne Water is exploring flood mitigation options for the Maribyrnong catchment, but these could take years to enact. We have recommended a support program to assist affected Rivervue residents who wish to leave in the meantime, and to cover direct financial losses they have already suffered.

In relation to Kensington Banks:

- No red flags stood out in the estate’s original design. Flood protection works at the site in the 1990s were based on good quality modelling and should have been enough to withstand flooding at levels predicted back then. But estimated flood levels are now higher than when the development was planned.

- Multiple factors contributed to the estate’s new flood risk status. The impacts of climate change and urban creep across the catchment are important drivers. Long gaps between flood model updates likely cost early chances to spot looming trouble. And a flood protection levee around the estate appears to have sunk in some places.

- Residents can have confidence in the latest Maribyrnong catchment model. Melbourne Water’s hasty release of results from its 2024 flood model fuelled community concern, but the model is modern, well designed and extensively tested. We have recommended some levee height checks to reinforce trust in the model’s results.

What needs to change

The experiences at Rivervue and Kensington Banks point to a need for broader reforms. We identified three key focus areas:

- Keeping the public informed with accurate and easy to find information. Flood models should be reviewed and updated regularly, with resulting flood maps promptly added to planning schemes. Creating a one-stop, statewide flood information portal will give people easy access to the latest modelling so they can make informed decisions about their safety and property.

- Planning for the impacts of climate shifts. Climate change threatens to upend traditional planning approaches. Catchments are changing, and homes built today must be designed to withstand tomorrow’s conditions. Planning decisions should consider longer-term flood projections, where available.

- Helping people living with flood risk. Major floods are projected to get larger in Victoria, and in coming years many other households will suddenly learn they are at increased risk of flooding. The situations at Rivervue and Kensington Banks are an opportunity to pilot new approaches to supporting people facing an uncertain future.

How Melbourne Water responded

Melbourne Water said it was committed to supporting our investigation, and engaged constructively throughout.

Before our work started, and amid other inquiries, it began overhauling its approach to flood modelling, including clear timeframes for reviewing and updating models, and incorporating climate change projections.

Melbourne Water told us it had learnt from community feedback around the release of the 2024 Maribyrnong catchment flood model, and would allow this to shape the rollout of its broader flood modelling program.

It also said it would work closely with the Victorian Government to address our recommendations.

Background

How we investigated

The Legislative Council referred a matter to us for investigation. Under our legislation, if either House of Parliament or a Parliamentary Committee refers a matter to us, we are required to investigate and report to Parliament without delay.

The referral required us to examine flood planning decisions for two housing developments in inner-Melbourne, both beside the Maribyrnong River:

- Rivervue Retirement Village (‘Rivervue’)

- Kensington Banks.

Many homes at Rivervue unexpectedly flooded in October 2022, when the Maribyrnong River burst its banks. Homes at Kensington Banks did not flood, but modelling done since shows both developments are at risk of future flooding.

The Legislative Council referral (see Figure 1) required us to look at past and current flood models for the Maribyrnong catchment, and planning decisions for both developments. It also required us to consider potential policy changes, and whether affected residents should receive compensation or other support.

Figure 1 Extract of Legislative Council referral letter

Source: Legislative Council

Submissions

The Legislative Council included a requirement for us to hold a day of public hearings as part of our investigation. However, we do not have the power to hold public hearings under the Ombudsman Act.

Instead, we invited submissions from Rivervue and Kensington Banks residents and other interested parties with information about flooding.

People making submissions were encouraged to share their experiences of the October 2022 flood and the 2024 release of new Melbourne Water flood maps, as well as any thoughts on improving how flood risk is managed.

We took submissions confidentially by phone, email, online form and in person. We received 59 in total, most online. This included 22 submissions from residents at Rivervue (all suffered flooding), 28 from residents at Kensington Banks, and a detailed submission from the Rivervue Residents’ Committee.

Residents quoted in the report are not identified by name to protect their privacy.

We also received submissions from:

- Melbourne Water

- Moonee Valley City Council

- the Municipal Association of Victoria

- the Maribyrnong Community Recovery Association

- the Kensington Association

- the Insurance Council of Australia.

Submissions helped us understand how people are impacted by flooding and flood-related planning decisions, and how these decisions are made.

We also spoke with engineering firms involved in past flood modelling, councils, community groups, local real estate agents and Rivervue’s owner to get a better understanding of the issues.

After reviewing the evidence, we also consulted with a range of government and non-government stakeholders about potential recommendations. We thank everyone who shared their knowledge and experiences with us.

Technical advice

We engaged a specialist to review Melbourne Water’s past and current flood models for the Maribyrnong catchment, and to provide us with other technical advice as needed.

Adjunct Professor James Ball is an academic in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Technology Sydney. Dr Ball was the technical editor for the most recent edition of Australian Rainfall and Runoff – A Guide to Flood Estimation. He is also former Editor-in-Chief of the International Journal of River Basin Management.

Dr Ball holds a PhD (Civil Engineering), Master of Engineering, and Bachelor of Civil Engineering, all from the University of Newcastle.

Access to records

The Ombudsman Act generally prevents us from receiving or reporting information about the ‘deliberations of Ministers’ – typically Cabinet information.

This prevented us from piecing together the development history of Kensington Banks. We were unable to access or reference some records because they related to Cabinet decision making.

Cabinet records generally remain closed to the public for 30 years. Some records we identified were old enough to be open, but the Ombudsman Act even prevents us from using Cabinet records which are now in the public domain.

At times, we also encountered another barrier we regularly encounter – incomplete records. Some key decisions for Rivervue were not well documented, and project records for Kensington Banks were not always easy to track down.

Interviewing former staff often improved our understanding of the facts. However, this was not always possible – due to the passage of time, some witnesses were difficult to track down, and others had passed away or were unavailable due to illness.

Procedural fairness

Our investigation was guided by the civil standard of proof which requires that the facts be proven on ‘the balance of probabilities’. This differs from the criminal standard of ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’.

To reach our conclusions, we considered:

- the nature and seriousness of the matters examined

- the quality of the evidence

- the gravity of the consequences an adverse opinion could create.

This report makes adverse comments, or includes comments which could be considered adverse, about Melbourne Water, Moonee Valley City Council, and the City of Melbourne. In line with section 25A(2) of the Ombudsman Act, we provided the relevant parties with a reasonable opportunity to respond to the report. This report fairly sets out their response.

We also provided excerpts of our report to other parties to confirm its accuracy.

In line with section 25A(3) of the Ombudsman Act, we make no adverse comments about anyone else who can be identified from the information in this report. They are named or identified because:

- it is necessary or desirable to do so in the public interest

- identifying them will not cause unreasonable damage to their reputation, safety or wellbeing.

Figure 2: Our investigation, by the numbers

3,853 documents reviewed 86,747 pages | |

9 witnesses interviewed | 4 summonses issued |

59 submissions received —22 from Rivervue residents —28 from Kensington Banks | 19 bodies consulted |

Source: Victorian Ombudsman

Other relevant reviews and inquiries

Other reviews and inquiries have looked at the causes and impacts of the October 2022 flood. These include:

- Melbourne Water’s Maribyrnong River Flood Event Independent Review reported in August 2023 on Melbourne Water’s flood models and the reasons for unexpected flooding at Rivervue

- the Legislative Council Environment and Planning Committee’s Inquiry into the 2022 Flood Event in Victoria reported in July 2024 on experiences across the state, including at Rivervue.

We considered the findings and recommendations of these reviews. Where possible, we have avoided duplicating past recommendations, but have noted when our views align.

Other past reviews and inquiries we considered include:

- the Legislative Council Environment and Planning Committee’s Inquiry into Climate Resilience , which reported in August 2025

- the Parliament of Australia’s House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics Inquiry into Insurers’ Responses to 2022 Major Flood Claims , which reported in October 2024

- the Victorian Government’s Review of the 2010-11 Flood Warnings and Response , which reported in December 2011.

| Flemington Racecourse floodwall out of scope We heard concerns that a controversial floodwall built to protect Flemington Racecourse had made things worse for neighbouring homes during the October 2022 flood. The Legislative Council did not specifically task us with investigating this issue and it was therefore not in scope. We did, however, note that the Maribyrnong River Flood Event Independent Review probed the wall’s impact in some detail. It concluded in April 2024 that the wall ‘did not have a measurable impact on Rivervue’, though did increase the depth of flooding experienced in some other areas. We also noted recent analysis commissioned by Melbourne Water on the wall’s likely future impacts in a larger, rarer flood. It found the wall might contribute to a slight increase in flood depth (less than 1 cm) at Rivervue, but would provide a ‘shielding’ effect at Kensington Banks. |

About the two developments

Rivervue

Rivervue is a ‘premium lifestyle’ retirement village for people aged over 55 beside the Maribyrnong River in Avondale Heights. A private company owns and operates it.

Rivervue is a mix of independent villas, apartments, and community facilities. Residents enter a contract with the village owner giving them a 99-year lease over their home.

A former site owner began planning Rivervue in the early 2000s, and building began after the current site owner bought it – with approved plans – in March 2010.

At the time of the October 2022 floods, there were 144 villas and 16 apartments at Rivervue, with more villas planned or under construction.

The flood left 45 villas unfit to live in for at least six months, and caused minor damage to two others. Shared areas such as a community centre, bowling green, and community gardens were also flooded. Residents have since been able to return to all homes.

Kensington Banks

Kensington Banks is a residential estate beside the Maribyrnong River in Kensington. It comprises more than 1,000 properties, occupied by a mix of owners and renters.

Located on the site of historic stockyards and abattoirs, it was conceived as part of the ‘largest inner urban residential project undertaken in Australia’.

Kensington Banks was primarily planned and overseen in the 1990s by the Victorian Government Major Projects Unit (‘Major Projects Unit’).

Private developers built homes from 1995 to the mid-2000s under a joint venture agreement with the Victorian Government.

The project involved flood defence works funded by the Australian Government and delivered by the Major Projects Unit.

Figure 3: Rivervue and Kensington Banks overview

Source: Victorian Ombudsman

The Maribyrnong River floodplain

The Maribyrnong River holds special significance to the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation. The name comes from the Woi-wurrung language spoken by the Wurundjeri people. The phrase ‘Mirring-gnay-bir-nong’ translates to ‘I can hear a ringtail possum’.

The Maribyrnong runs for 160 kilometres, starting as a small stream at Mount Macedon and eventually feeding into Port Phillip Bay. Its lower reaches are heavily developed, with many homes and businesses on or near the floodplain.

Some key terms used in this report *

| 1% AEP flood: used as a benchmark for planning. There is a 1-in-100 chance a flood this size (or larger) could occur in any given year. See the ‘What does 1% AEP flooding mean?’ explainer box for more detail on this. |

| Catchment: area of land where rainwater collects and feeds into the river |

Flood: when water covers land that is usually dry. There are three main types of flooding:

|

| Floodplain: land next to a stream or river that is prone to flooding |

| Flood defence: structure or system put in place to reduce flood risk |

| Flood hazard: potential harm caused by flooding |

| Flood level: estimated height above sea water a flood might reach. Also referred to as ‘flood line’ in this report |

| Flood line: see above |

| Flood map: map showing how areas are likely to be affected by flooding |

| Flood model: tool used to predict flooding, including where water could go, and how deep it could get |

| Flood risk: how likely it is a flood will occur, and the consequences if it does |

| Freeboard: a safety buffer added to raise floor levels above the expected flood height |

* See the more detailed glossary in Appendix 2 for other important terms.

History of the Maribyrnong River flooding

The Maribyrnong River has a long history of breaking its banks, with 18 major floods recorded since 1871.

The October 2022 flood was the third largest on record. Flood waters at the Maribyrnong gauge on Chifley Drive reached 4.22 metres, the highest in more than 100 years.

Other major floods include:

- 1906, the highest recorded, when flood waters reached 4.5 m

- 1916, the second highest, when flood waters reached 4.26 m

- 1974, when flood waters reached 4.2 m. Although slightly smaller than the October 2022 flood, it caused significant property damage.

Managing the floodplain

Flooding is a natural hazard. While good for the ecosystem, it can cause major disruption and harm to local communities.

Floodplain management seeks to reduce losses caused by flooding, while ensuring the floodplain performs its important natural functions.

A range of stakeholders work to manage floodplains in Victoria. Figure 4 shows those most relevant to our investigation:

Figure 4: Key floodplain management stakeholders

Modelling flood risk

A core element of floodplain management is flood modelling. Among other things, flood models predict where flooding could go and how deep it could get. Consultants generally prepare the flood models and hand them over to Melbourne Water or councils to use and adapt over time.

Experts enter data about rainfall, land features, river flow, climate and other factors into a complex computer model to produce a ‘flood map’ showing areas likely to be affected. The models also produce estimates of water depth, known as ‘flood levels’. These are usually expressed as a height above average sea level in line with the Australian Height Datum (‘AHD’) system. This report uses AHD levels unless specified.

Flood maps and levels are estimates only, based on probability, and all flood models involve a degree of uncertainty. They are usually revised and updated as modelling techniques improve, and catchment conditions change. Because real floods differ in size and frequency, a hypothetical benchmark is used for planning purposes, known as a ‘design flood’.

In Victoria, this is the 1% Annual Exceedance Probability (‘1% AEP’) flood. Put simply, this means there is a 1 in 100 chance a flood this size (or larger) could occur in any given year.

What does 1% AEP flooding mean?

The 1% AEP flood is sometimes referred to as a ‘1 in 100-year’ flood. This can be misleading, as it suggests floods of this size only happen once a century, when they can happen more frequently.

A 1% AEP flood is commonly used for land planning, with boundaries marked on flood maps. Homes within these areas are built to withstand 1% AEP floods, though a small chance of flooding always remains. Properties sitting outside marked 1% AEP areas may still be at risk of flooding too during rarer, larger floods.

The likelihood of experiencing a flood also increases the longer a person lives in their home. As Figure 5 shows, a property in a marked 1% AEP area has a 26 per cent chance of experiencing a flood that size or larger over the life of a standard 30-year mortgage.

Figure 5: Chance of experiencing flooding increases over time

Chance of flooding based on how long you live at address | |||

Type of flood | 1 year | 30 years | 100 years |

Smaller, more common flood 1 in 20 chance each year (5% AEP) | 5% | 79% | 99% |

Large ‘design’ flood 1 in 100 chance each year (1% AEP) | 1% | 26% | 63% |

Larger, rarer flood 1 in 200 chance each year (0.5% AEP) | 0.5% | 14% | 39% |

Source: Victorian Ombudsman

Three relevant models

The full Maribyrnong catchment covers more than 1400 square kilometres, so models usually predict flood risk for specific segments.

Over the years, Melbourne Water has modelled the catchment three times:

- The 1986 model formed part of a broader flood mitigation study. It looked at flood risk in the lower part of the catchment, where Kensington Banks was later built. It did not cover the future Rivervue site.

- Combined 2003 modelling was prepared by consultants to Melbourne Water’s specifications. It updated the 1986 model and predicted flood risk for a larger section of the catchment. Some notable flaws with this modelling have since emerged. It was made up of three separate parts:

- the 2003 lower model covered the lowest reaches of the catchment, including the Kensington Banks area

- the 2003 mid model covered an area directly upstream, including the Rivervue site

- the 2003 upper model covered a separate part of the catchment.

- The 2024 model was planned before the October 2022 flood, but completed afterwards. It covered the same areas as the 2003 modelling, but was prepared by different experts. Its release surprised many Kensington Banks residents who suddenly discovered they lived in a floodplain.

When preparing flood models, Melbourne Water is guided by:

- Australian Rainfall and Runoff: A Guide to Flood Estimation , the leading technical guide published by the Australian Government (and formerly by Engineers Australia)

- internal technical specifications, chiefly the AM STA 6200 Flood Mapping Projects Specification

- the Victorian Flood Data and Mapping Guidelines , non-technical guidance from the former Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning.

Figure 6 shows the areas covered by the 2003 lower, mid and upper models:

Source: Victorian Ombudsman. Not to scale.

Controlling development

Flood model results guide land use planning, which is an important part of managing a floodplain. It involves controlling the use and development of land.

Local planning schemes set the rules for planning decisions. This is done through planning controls such as:

- zones which set out the purpose of land and how it can be used (eg residential development or agriculture)

- overlays which identify land where specific controls are required (eg due to natural hazards such as flooding or bushfires).

When a flood model produces a new flood map it is usually inserted into the planning scheme by updating these controls.

There are four flood-related planning controls. The most appropriate depends on the type of flooding and degree of hazard. The two most relevant to our investigation are:

- the Land Subject to Inundation Overlay, which covers land affected by flooding from waterways and coastal areas. Building in this overlay requires a permit.

- the Special Building Overlay, which covers areas prone to flooding from stormwater or if drains fail. Building in this overlay also requires a permit.

Clauses in the planning scheme set out criteria for development in each zone and overlay. These are drawn from the statewide planning framework, the Victoria Planning Provisions .

Flood risk at Rivervue

Residents did not expect the flooding experienced at Rivervue in October 2022, as the site was not formally flagged as flood prone.

The deluge caused major property damage and significant distress. Many residents were evacuated, with some unable to return home for months. Prized possessions were lost, and a fear of future flooding lingers.

The Legislative Council required us to investigate the removal of a key flood planning control over Rivervue in 2016. As part of this we reviewed Rivervue’s broader development history to establish why homes flooded.

We also looked at the ongoing impacts on residents and the challenges they face spending their retirement in a floodplain.

Figure 7: Overview of key events

Source: Victorian Ombudsman

Development of Rivervue

The Rivervue site was historically used as a market garden but had sat vacant for many years before planning for the lifestyle village began.

Various earlier development attempts failed to get off the ground. A key challenge was that some of the land sat within the known floodplain and had a planning control known as a Land Subject to Inundation Overlay (‘LSIO’) over it, limiting development options.

| About Land Subject to Inundation Overlays |

An LSIO is a planning control applied over land at risk of flooding. It is shown on planning maps overseen by the local council. Development in an LSIO area is not banned, but requires a referral to the relevant floodplain authority – in this case, Melbourne Water. The authority assesses whether the proposed development is appropriate and if any extra permit conditions should apply. Melbourne Water can object to development in an LSIO within its catchment areas. Elsewhere, other catchment management authorities provide advice, but do not have final say. LSIOs are inserted and updated through the planning scheme amendment process. Boundaries are based on the 1% AEP ‘design flood’ – ie land that has a 1 in 100 chance of flooding in any year. |

Planning permit granted

Planning for Rivervue started in earnest in 2002 with the site’s former owner approaching Melbourne Water for flood information about the land.

Melbourne Water gave some general information about developing in the floodplain, and encouraged the former site owner to get technical advice about the possibility of filling the site to lift it above the flood line.

The former site owner followed this advice, and engaged a consultant engineer to design flood protection works to raise part of the land to allow homes to be built.

Melbourne Water reviewed this design, obtained further information, and decided the works would appropriately manage flood risk.

With the design in hand, the former owner applied to Moonee Valley City Council for a planning permit to modify the floodplain and build a combined retirement village and nursing home.

Due to the LSIO over part of the site, the council referred the planning application to Melbourne Water. Melbourne Water told the council it did not object to the proposal if certain conditions were included in the planning permit.

The council did not decide on the planning permit within the required timeframe, so the former site owner lodged an application with the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (‘VCAT’).

As part of the proceedings, the council told VCAT that if it had acted in time, it would have rejected it for multiple reasons – but not flood risk.

On 21 June 2006, VCAT directed the council to issue the planning permit. VCAT said although the development carried ‘some risk’, it was satisfied that all homes could be built well above the flood line.

Melbourne Water did not attend the VCAT hearing. This was not unusual because it had already decided it was comfortable with the proposed development.

The council complied with VCAT’s order to issue a planning permit to the former site owner.

Planning for Rivervue continued over the following years, with the council approving a range of technical reports and plans.

In March 2010, the former owner sold the site, with plans included.

The current site owner told us it bought believing that by completing the flood protection works already approved by Melbourne Water, no homes would be at risk of flooding.

After buying, the current site owner sought consent to delete the planned nursing home and build only the retirement village.

With this approval in place, the current owner started developing the site.

Flood protection works completed

To ensure homes at Rivervue were safe, flood protection works were planned and undertaken at the site.

Works were designed to handle predicted flood levels produced by Melbourne Water’s 2003 mid model. (Some significant flaws in this model are discussed in detail later in this chapter).

The planned works were updated several times over the years before being finalised in December 2010, as development got underway.

Core elements were:

- filling part of the site so homes would sit above the flood line

- excavating and landscaping the remaining floodplain area to offset the loss of flood storage created by the filling

- including a safety buffer so floor levels at all homes would be at least 60 cm above the flood line.

The works were supported by a series of technical reports by Rivervue’s consultant engineer. Their modelling showed that excavating and filling different parts of the site would not worsen flooding in the surrounding areas.

Melbourne Water signed off on the flood protection design. It also consented to changes made as the development took further shape.

In 2015, the current site owner completed the flood protection earthworks, and homes were built on the raised section of land.

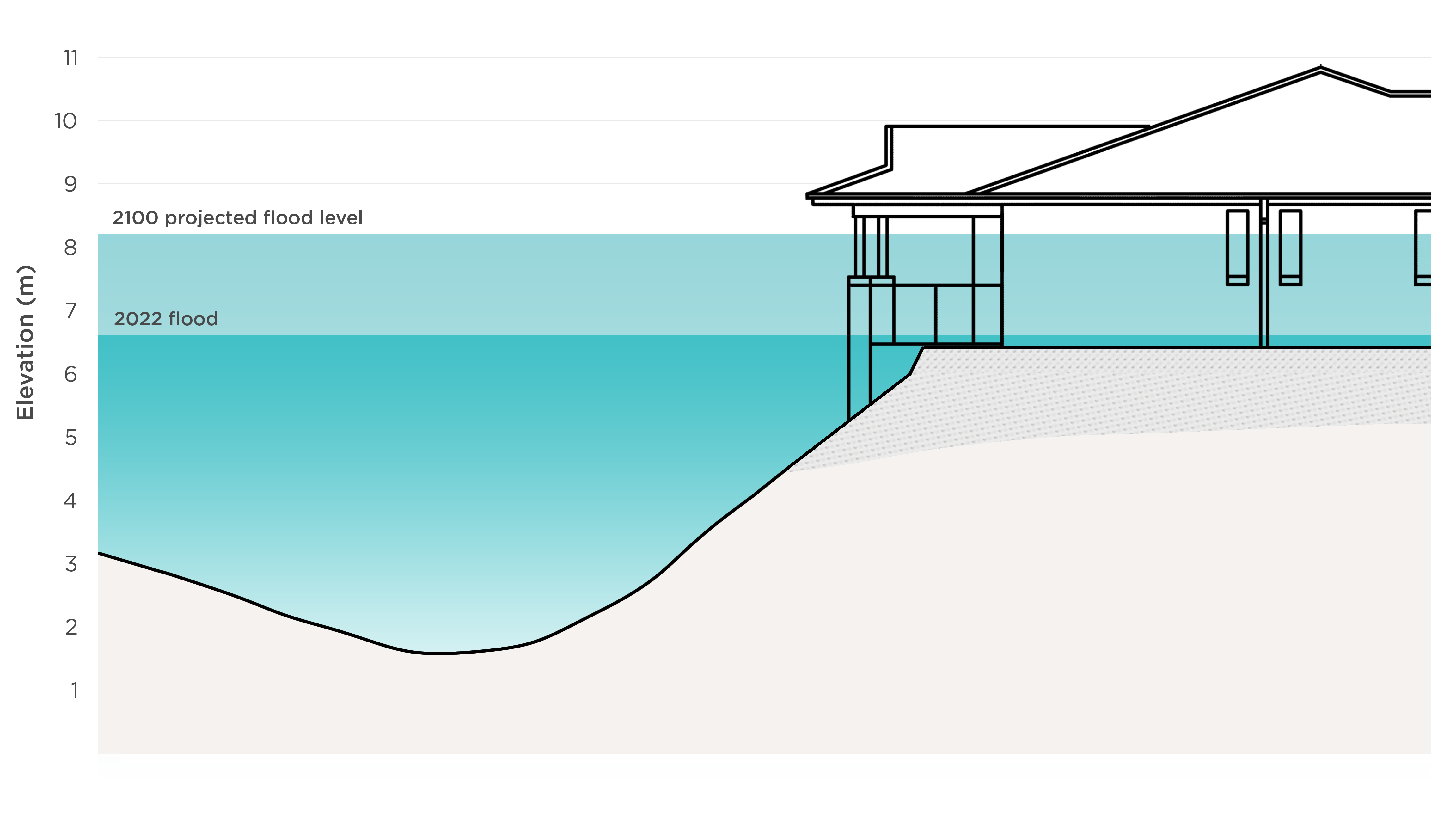

Figures 8 and 9 show how the floodplain modification works were designed to deal with flooding at Rivervue:

Floodplain mitigation works are typically designed to handle existing catchment conditions. In the case of Rivervue, developers had only to fill the earth centimetres above the estimated flood level. The addition of a 60 cm safety buffer for homes meant older people were then clear to move in.

Figure 8: Rivervue site before development

Source: Victorian Ombudsman. Not to horizontal scale.

Figure 9: Floodplain modification works, as designed

Source: Victorian Ombudsman. Not to horizontal scale.

No safety assessment

Different Melbourne Water teams looked at different aspects of the Rivervue flood protection works. Drainage issues, waterway health, and broader floodplain impacts were all separately assessed. In a memo endorsing the works, one team noted that ‘matters related to safety’ should also be considered.

We did not find evidence that a separate safety assessment was conducted, or suggesting Melbourne Water considered the specific risks of a large group of vulnerable older people living on a reclaimed floodplain.

Melbourne Water now takes a hazard-based approach to assessing development, which looks at the particular vulnerabilities of buildings and people using the site.

Figure 10: Timeline of key LSIO events

Source: Victorian Ombudsman

Flood planning controls removed

Not long after flood protection earthworks were completed, the LSIO planning control at Rivervue was adjusted to remove the raised section of the site where homes were built.

This happened as part of broader changes to the Moonee Valley Planning Scheme known as Amendment C151.

Removing the LSIO meant Melbourne Water would no longer be referred new planning permit applications for that part of the Rivervue site, but would maintain responsibilities under the existing permit. It also meant homes would not be flagged as flood prone in official information sources relying on the planning scheme.

The October 2022 flood later showed this was the wrong decision. Flooding impacted many homes that were formerly in the LSIO area. The flood was smaller than the ‘design flood’ the LSIO was intended to reflect, highlighting how unreliable the new boundaries were.

We explore how this planning control was removed and its consequences for residents below.

Figure 11: LSIO in Moonee Valley Planning Scheme, before amendment

Source: Victorian Ombudsman

Figure 12: LSIO in Moonee Valley Planning Scheme, after amendment

Source: Victorian Ombudsman

Planning scheme amendment proposed

The planning scheme amendment updated a range of flood-related planning controls across the Moonee Valley local government area – not just those at Rivervue.

It was started in July 2015 by Moonee Valley City Council at Melbourne Water’s request. Melbourne Water had recently completed new overland flow and drainage modelling and wanted this reflected in the planning scheme. These changes did not impact the Rivervue site.

However, the amendment also included proposed updates to the LSIO. These generally adjusted the LSIO boundaries to match Melbourne Water’s 2003 flood modelling which, although more than a decade old, had not yet been reflected in the planning scheme.

Included in this second set of changes was a proposal to expand the LSIO over a small part of the Rivervue site.

After moving through the usual process, the proposed amendment was put out for public comment. The council officially notified impacted landowners, including Rivervue’s current owner.

Objection lodged

Proposed changes to the LSIO at Rivervue were based on maps from Melbourne Water’s 2003 flood modelling, which predicted where flood water would go based on what the land looked like back then.

But by the time the changes were exhibited in 2015, Rivervue’s current owner had completed earthworks altering the floodplain.

When notified of the proposed changes to the LSIO, Rivervue’s owner objected, pointing out the amendment failed to factor in changes to the land which had ‘removed’ part of the site from flooding.

The owner asked for the boundaries to be adjusted to reflect the completed modification works – in effect, to remove all homes from the LSIO area.

Objection considered

When an objection is made to a proposed planning scheme amendment the planning authority can try to ‘resolve’ it by reaching an agreement with the other party. The authority can also seek further advice from the amendment proponent – in this case, Melbourne Water.

If agreement still is not reached, the next step is usually to set up an independent planning panel to consider the objection.

In keeping with the first stages of the objection process, the council forwarded the Rivervue owner’s objection to Melbourne Water for advice.

Melbourne Water obtained an ‘as built’ survey from Rivervue’s owner showing the completed earthworks and compared the new landscape with the estimated flood levels for the site.

From this, and accounting for flood storage and other considerations, it decided the relevant section of Rivervue was no longer in the floodplain – that is, all areas were above the 1% AEP ‘design flood’ used for planning purposes.

After reviewing the details, Melbourne Water told Rivervue’s owner it would revise the proposed LSIO boundaries to match the development line created by the recent earthworks.

In November 2015, Melbourne Water advised the council it had resolved the objection, supplying a new LSIO map for the Rivervue area.

However, by this time the council had already moved to the next stage, and arranged to set up an independent planning panel to consider the matter.

Planning panel considers amendment

Planning panels are established by Planning Panels Victoria – currently within the Department of Transport and Planning.

Planning panels are made up of one or more specialists. The main purpose is to consider unresolved submissions (including objections) about a proposed planning scheme amendment. The panel advises whether to abandon the amendment, change it, or adopt it as is.

The panel set up for Amendment C151 comprised a single expert (‘the Chair’), who was asked to consider a range of submissions. This initially included the Rivervue owner’s objection.

However, the Chair was notified soon after the process started that Melbourne Water and the council had already resolved the Rivervue objection by making changes (described above). This meant, in effect, there was no disagreement about Rivervue left for the Chair to consider.

After hearing from the council, Melbourne Water, and remaining objectors, the Chair recommended the council progress the amendment with some changes. This included the LSIO edits prepared by Melbourne Water at the request of Rivervue’s owner.

In February 2016, the council followed the Chair’s recommendations, and submitted the proposed amendment to the Minister for Planning for consideration. The amendment was then considered and approved by a delegate of the Minister. It came into operation on 4 August 2016.

Removing the LSIO lifted restrictions on future development at Rivervue, but did not change its existing planning permit, with all conditions previously imposed by Melbourne Water kept in place.

| Planning panel not informed of age of flood modelling

The main catalyst for the 2016 planning changes was new ‘overland flow’ modelling by Melbourne Water showing how rainwater would likely behave. This 2014 flow modelling, which centred on stormwater and drainage rather than on river flooding, prompted updates to the Special Building Overlay in the planning scheme. However, the changes to a range of LSIO maps that went through at the same time were based on much older information – the 2003 flood modelling, which by then was 13 years old. Documents put before the Chair created an impression all changes to flood maps were based on ‘more advanced’ flood modelling which had been ‘recently undertaken’ by Melbourne Water. At interview, the Chair told us they were not aware of the age of the Maribyrnong catchment flood model used to support the LSIO changes. The Chair said if they had been made aware of this and other shortcomings (discussed later), they would have sought further information from Melbourne Water, and could have approached their decision differently. Melbourne Water staff told us they were not sure why flood maps from the 2003 modelling only reached the planning scheme in 2016. However, such amendments are expensive and time consuming, and the changes were not extensive. Long delays getting new modelling into planning schemes are common. We discuss this problem in more detail later. |

Was removal of the LSIO reasonable?

It is not unusual for planning controls to be removed following floodplain modification works. This also happened at Kensington Banks (discussed in the next chapter).

We saw no evidence of improper influence or other irregularity in how the LSIO was removed at Rivervue. Yet removal was clearly the wrong decision, given the subsequent flooding of homes.

It is hard to fault the council, the Chair, or the Minister’s delegate. All supported the LSIO changes based on technical advice from Melbourne Water about where flood waters would go.

It was reasonable at the time to rely on this advice because Melbourne Water was the floodplain management authority and there were no obvious ‘red flags’.

Only much later – after Rivervue flooded – did it emerge that Melbourne Water’s advice was based on unreliable flood levels from a flawed model. We discuss this in more detail below.

Problems exposed by the October 2022 flood

Flooding at Rivervue started on the morning of 14 October 2022, following four days of intense rain across Melbourne in already wet conditions.

Stunned residents watched as water filled some of the village streets, courtyards and, inside some homes, began to spout from sinks and drains.

All we heard from were taken by surprise. Some said they had previously wondered about flooding at Rivervue and been reassured there was no risk, or told ‘not in your lifetime’.

Residents watched with alarm as a foul blend of the surging river, stormwater and sewage invaded some homes and lapped at the bottom of walls and furnishings. Many other homes higher up a hill were untouched.

Neighbours and village staff rushed to help as affected residents – some frail or in poor health – did their best to move whatever they could to higher ground before fleeing.

A daunting clean-up awaited their return. Contaminated water caused significant damage to 45 homes. About 70 residents were forced to move out, some for many months.

Some were able to fall back on family and friends for support. Others struggled to find stable shelter, with short-term stay options nearby scarce and expensive.

Rivervue’s owner paid for some emergency housing costs in the initial weeks after the flood, even though this was not covered by its insurance.

But with homes taking on average six months to rebuild, many residents were left significantly out of pocket. For example, one told us they were forced to spend a total of $18,000 on temporary accommodation, removal and storage costs.

Repairs to damaged units were funded by Rivervue’s owner, despite its lack of full insurance cover. However, many residents did not have their own policy to cover home contents and personal belongings such as clothing, appliances and furniture.

We discuss the longer-term impacts of flooding – including on property values, insurance and resident health and wellbeing – in more detail elsewhere in this report.

Figure 13: What we heard from Rivervue residents

Source: Submissions to the Victorian Ombudsman

Figure 14: Extent of flooding at Rivervue in October 2022

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on modelling for Melbourne Water

| Case study 1: Couple watches in ‘absolute despair’ as flood waters ruin home |

The October 2022 flood waters that wrecked the Rivervue home Kevin shares with his wife have taken a heavy toll on the couple, now aged in their 80s. Their home since 2017 was ‘completely inundated’, resulting in damage so extensive they had to move out for about a year and live with family. Kevin told us after being alerted to rising water by his neighbour, he did his best to rescue as many items as possible, but much was lost as he watched on: The loss of personal belongings and memorabilia reminds us on a regular basis of the absolute despair and feeling of regret that we felt as we stood and watched our home being flooded from both the river and the storm water drains in the street that we mistakenly thought would save us. Things lost after 60 plus years of life together are not replaceable, our failing memories are our only records. Kevin and his wife were attracted to Rivervue for the lifestyle, convenience and health services available, describing it as ‘a wonderful place to live’ until the flood. Kevin told us that since the flood, his health has deteriorated, and he is now restricted and unable to fully ‘enjoy life as you would expect to enjoy it in a lifestyle village’. ‘My wife is also a very different person to what she was before the flood, continuously referring to things that she can’t find and reliving the flood experience,’ he says. Kevin says he expects their health to ‘further decline … until we are offered some form of mitigation work’. The possibility of another flood is a constant worry, particularly during heavy rain. ‘We are now both in our eighties and the prospect of our physical and mental survival should this happen again is a massive concern to us, and more importantly to our families,’ Kevin says. |

Why did Rivervue flood?

We found Rivervue flooded due to a combination of two design problems:

- flawed flood modelling: avoidable faults meant flood protection works and homes were designed and built too low

- incorrect floor levels: errors in approved building plans meant some homes were built even lower.

Figure 15 shows the combined effect of the two problems:

Figure 15: Problems with Rivervue homes, as built

Source: Victorian Ombudsman. Not to horizontal scale.

Flawed 2003 modelling

Flood protection works at Rivervue were designed to handle estimated flood levels provided by Melbourne Water.

These were taken from the 2003 mid model. It is now known this model was not fit for purpose and produced flood levels that were too low. As a result, Rivervue was also built too low.

We found Melbourne Water developed the flood model hastily, soon after it first became aware of the proposed Rivervue development. This haste meant a range of problems went overlooked.

We explore how this happened below.

No previous model

When Rivervue’s former owner first approached it, Melbourne Water did not have a flood model for the mid-section of the Maribyrnong catchment. Its 1986 model covered some of the Maribyrnong catchment, but not the Rivervue site.

This was not unusual for the time, as there was little development occurring in the mid-section, where most land was public or open space.

While Melbourne Water had some designated flood levels for the Rivervue site, staff were not sure where they had come from, and were not confident about them. Internally, they suspected the levels were based on flood marks from the last major Maribyrnong overflow in 1974.

With the former Rivervue owner wanting to develop the land, Melbourne Water recognised it needed more reliable flood data.

Consultants engaged

In June 2003, Melbourne Water engaged a consultant engineering firm to prepare a new flood model for the mid-Maribyrnong catchment, including the Rivervue site.

The same firm had recently prepared a similar flood model for the lower section of the catchment.

Melbourne Water asked the consultants to prepare the new model in ‘approximately 2 weeks’. Under the terms of the engagement:

- Melbourne Water agreed to provide much of the data required

- ‘no allowance’ was made for checks and adjustments of the model – known as calibration - against historic floods.

Current and former Melbourne Water staff familiar with the 2003 mid model told us they were not entirely sure why Melbourne Water set such a tight deadline. They agreed it was probably to ensure the new model was ready to inform the Rivervue development.

The consultants supplied new flood levels within a month, and Melbourne Water gave these to Rivervue’s engineer.

Model underpredicts flood levels

The 2003 mid model predicted flood levels at the future Rivervue site ranging from 6.0 m at the northern boundary to 6.4 m at the southwest.

This was for a 1% AEP flood – that is, a flood with a 1 in 100 chance of occurring or being exceeded in any given year.

The October 2022 flood was considered less severe than a 1% AEP event. Yet actual flood waters at Rivervue ranged from about 6.5 m to 6.8 m – much higher than the 2003 mid model predicted for a 1% AEP flood.

Analysis later done for Melbourne Water concluded the model was ‘not a suitable tool for floodplain management’.

Problems with the model

Multiple problems with the 2003 mid model should have been evident to Melbourne Water staff at the time, but were missed.

The first major red flag was that the model predicted levels for a rarer flood than in 1974, yet indicated water levels at Rivervue would be lower.

During the 1974 Maribyrnong River flood, water at the northern Rivervue boundary reached 6.07 m.

The 2003 mid model produced an estimated flood level at Rivervue of 6.0 m – lower than the actual level experienced in 1974.

This fact on its own should have prompted further investigation into the model’s reliability. Yet as best we could tell, nobody at Melbourne Water noticed.

The second red flag for the 2003 mid model was the rush to deliver it. High quality flood modelling usually takes about a year to complete. Melbourne Water instructed its consultants to prepare the model in just two weeks. This was not enough time for a rigorous process.

Lack of time led to the third red flag: the model was not calibrated.

Calibration has long been a standard step when preparing a flood model. It involves sense-checking the new estimates against historic data and, if necessary, adjusting the model to improve reliability.

Uncalibrated flood models are less reliable. Yet the 2003 mid model was left unchecked despite:

- suitable historic flood data existing

- the consultants telling Melbourne Water they could calibrate the model if requested.

The consultants told us calibrating the 2003 mid model, as they offered to do at the time, would have involved consideration of records from the 1974 flood. This likely would have highlighted the discrepancy between the flood levels observed in 1974 – which were not provided to the consultants – and those predicted by the model.

At interview, a Melbourne Water officer involved in engaging the consultants said the most likely explanation for some of the model’s shortcomings – such as the lack of calibration – was the ‘relatively short amount of time’ the consultants had to prepare it, given the pending development application for the Rivervue site.

Another possible contributor was the controversial Flemington Racecourse wall. At the same time Melbourne Water was engaging consultants to prepare the 2003 mid model, it was also assessing a permit application from the Victoria Racing Club.

At interview, the former Melbourne Water officer involved in commissioning the 2003 mid model acknowledged it became ‘a little bit of a side event’. Given the higher flood risk associated with the racecourse proposal, they remarked: ‘That’s where our attention was focused, … where the risk was’.

The 2003 mid model report was not provided to Rivervue’s engineer – only the computer model and estimated flood levels. This meant Rivervue’s owner was not in a position to identify the problems with it.

Rivervue’s engineer told us they were not provided with the 1974 flood levels, and would ‘no way’ have accepted the results from Melbourne Water’s 2003 mid model if made aware of the discrepancy between its predictions and previously observed flooding at the site.

The consultants emphasised to us that they prepared the model in line with Melbourne Water’s specifications, and had no control over how it was adapted and used. We do not suggest they are responsible for the planning failures at Rivervue.

Incorrect floor levels

The second key contributor to flooding at Rivervue was that some homes were built lower than they should have been.

This happened after site plans were changed by Rivervue’s former owner. The revised plans – signed off by Melbourne Water – mistakenly used the wrong set of numbers for calculations.

This worsened the problem caused by flaws in Melbourne Water’s modelling which saw floor positions already too low.

Some floor levels lowered

Rivervue’s planning permit included a range of conditions requested by Melbourne Water.

One was that finished floor levels in each home needed to be built at least 60 cm above the ‘applicable flood level’.

Inclusion of such a safety buffer, known as ‘freeboard’, is standard when building homes in areas prone to flooding.

Homes across Rivervue were to be built at different elevations, based on the site terrain. Melbourne Water’s model estimated flood levels ranged from 6.0 m to 6.4 m. If used, these figures should have resulted in minimum finished floor levels between 6.6 m and 7 m – at or slightly above the peak of the October 2022 flood.

Site plans originally submitted by Rivervue’s former owner in 2004 reflected this.

However, in March 2009 the former owner requested the council and Melbourne Water’s consent to slightly lower floors in some homes, including 25 at ground level.

To support its request, the former owner submitted new site plans. These mistakenly relied on different flood levels to the previous plans when calculating the floors.

New floor levels proposed by the former owner for those homes affected by the change now ranged from 6.45 m to 6.76 m – in all but one case lower than required.

This meant floors were still marginally above the estimated flood level, but without the full 60 cm safety buffer.

Melbourne Water overlooked this error, and incorrectly signed off on the requested changes. The council then endorsed the new site plans.

Melbourne Water was unable to tell us why it missed the error. The decision was made 16 years ago, and we were unable to locate the officer responsible. No records were apparently kept of the decision-making process, although Melbourne Water said it believed some were potentially created and misplaced.

In our view, the most likely explanation was confusion between two different types of flood levels produced by modelling:

- The first type is known as the ‘water surface elevation’. This is used as standard industry practice for setting floor levels, and Melbourne Water usually requires floor levels based on this figure.

- The second type is known as the ‘total energy line’. This shows the potential increase in flooding when water is obstructed, and is always higher than the first type.

Melbourne Water had specified it wanted all Rivervue floor levels based on the less commonly used second type.

At interview, a former Melbourne Water staff member involved in the decision said the more ‘conservative’ second type was probably chosen for Rivervue due to higher water velocity in the area.

However, those involved in redrawing site plans in 2009 appear to have mistakenly defaulted to the first type when updating floor levels.

Because standard practice was to use the first type, all those involved with preparing and reviewing the revised Rivervue plans may have assumed this applied.

Our analysis of the revised floor levels reinforces this possibility. It shows they are almost exactly 60 cm higher than the first type, rather than the second type Melbourne Water wanted used.

Rivervue changed hands soon after the new site plans were approved by both Melbourne Water and the council, and the current owner’s due diligence process did not identify the problem.

From this point on, all further site plans continued to use the incorrect, lower flood levels.

This is important, as over time it allowed floor levels to be lowered even further in some homes – up to 30 cm below what was originally intended.

Further updates to site plans over the years meant Melbourne Water missed additional opportunities to identify the error, as later stages of the development repeated the mistake.

Missing permit footnote contributes to confusion |

We noticed a formatting mix-up in the Rivervue planning permit that possibly contributed to the confusion which resulted in floors being too low. When it agreed to the development, Melbourne Water asked Moonee Valley City Council to include several conditions in the permit. A key one was that finished floor levels in homes be at least 60 cm above the ‘applicable flood level’, a standard safety buffer. Melbourne Water asked the council to include a usual footnote clarifying that the estimated flood level across the site ranged from 6.0 m to 6.4 m. However, the format of the permit ordered by VCAT (and later granted to the former owner) did not include the intended footnote. Instead, the information was inserted as a separate clause in an unrelated section of the permit, under ‘Stormwater Quality’. Although seemingly minor, this formatting mix-up had potentially serious consequences. It made it difficult to determine at a glance what the ‘applicable flood level’ was supposed to be when designing floor levels in homes. The same issue carried into the later, amended permit issued when the nursing home was removed from plans. |

Combined impact

These two issues – the flawed flood modelling and the incorrect floor levels – were compounding. With only one and not the other, it is likely homes at Rivervue would not have flooded in October 2022.

The flawed modelling meant Rivervue’s flood protection works were designed to deal with estimated flooding well below the reality.

Even then, the additional 60 cm floor safety buffer should have been enough to protect most homes. But the mix-up in site plans meant this buffer was not fully implemented. All homes which experienced major flooding in October 2022 were built without the full buffer.

Conversely, the plans mix-up may not have led to flooding in 2022 if Melbourne Water’s flood levels were reliable. More accurate levels would have seen homes built much higher.

It was only through a combination of these errors that flooding at Rivervue happened.

Both errors were made well before the removal of the LSIO. We found the LSIO change did not directly contribute to flooding – although it may have given a false sense of security.

Flood risk at Kensington Banks

Kensington Banks did not flood in October 2022. However, in 2024 new flood modelling by Melbourne Water indicated about 850 of the estate’s more than 1,000 properties are at risk of flooding.

This news came as a shock to residents, many of whom bought homes understanding they were free from flood risk, and instead face an uncertain future.

The Legislative Council asked us to investigate the development of Kensington Banks, including the flood modelling relied on and the flood protection works done at the site.

We also looked at how the unexpected announcement of the area’s new flood status has impacted residents.

Figure 16: Overview of key events

Source: Victorian Ombudsman

Homes built on land with a long history of flooding |

Land used for Kensington Banks was part of an area prone to frequent flooding and historically known as the ‘South Kensington swamp’. The earliest recorded flood hit the area in 1893, when the Maribyrnong River (then known as the Saltwater) reportedly ‘overflowed’. The site flooded again in 1906, destroying a nearby bridge, and in 1909, leaving the abattoirs and nearby properties ‘surrounded’ by flood waters. Opponents of a doomed expansion of livestock saleyards at the site in the 1920s and 1930s called the proposal ‘sheer stark-staring madness’ given the flood risk. Newspapers described the area as a ‘dismal vista of swampy clay, of miniature lakes and of boggy depressions, surrounded by factories engaged in noxious trades’. Efforts to fill the area for housing had been discussed since the nineteenth century, long before the Kensington Banks project was first proposed. |

Development of Kensington Banks

Like Rivervue, Kensington Banks has a long and complex development history spanning several decades.

Built from about 1994 to the mid-2000s, the estate was originally part of a larger urban renewal project known as ‘Lynch’s Bridge’.

That project launched in 1982 after a Melbourne Water planning study recommended a ‘major effort should be made … to clear the floodplain of undesirable developments’.

The study pointed to flood-prone industrial land used by Melbourne City Council Abattoirs as one site worthy of redevelopment.

A working group established by the Victorian Government to consider ‘more appropriate uses’ of the area looked at multiple proposals over the following years, including for a caravan park or conference centre.

Each was blocked, amid strong Melbourne Water opposition to any uses involving ‘unacceptable risk’ to safety.

Suggestions to fill the land and build houses were also quickly knocked back, with Melbourne Water observing in 1987 that sections of flood prone land ‘could not receive any form of residential development’.

This resistance eased in 1991, when the Victorian Government Major Projects Unit prepared a detailed flood protection plan, which it argued would allow homes to be safely built on the site and nearby public land.

Flood protection works completed

Flood protection works – refined with Melbourne Water input and co-funded by the Australian Government – began in 1992. Private developers then built homes from 1995 to the mid-2000s under a joint venture agreement with the Victorian Government.

Homes were designed and built to development plans inserted into the Melbourne Planning Scheme, generally doing away with the requirement for individual planning permits.

Unlike at the privately developed Rivervue, the Victorian Government played an active role in planning and overseeing Kensington Banks. This included:

- handling land sales

- designing and implementing flood protection works

- preparing the area for development

- arranging for planning approvals.

As at Rivervue, Melbourne Water also played an active role:

- reviewing the flood protection plan

- scrutinising the development proposal

- removing flood-related planning controls.

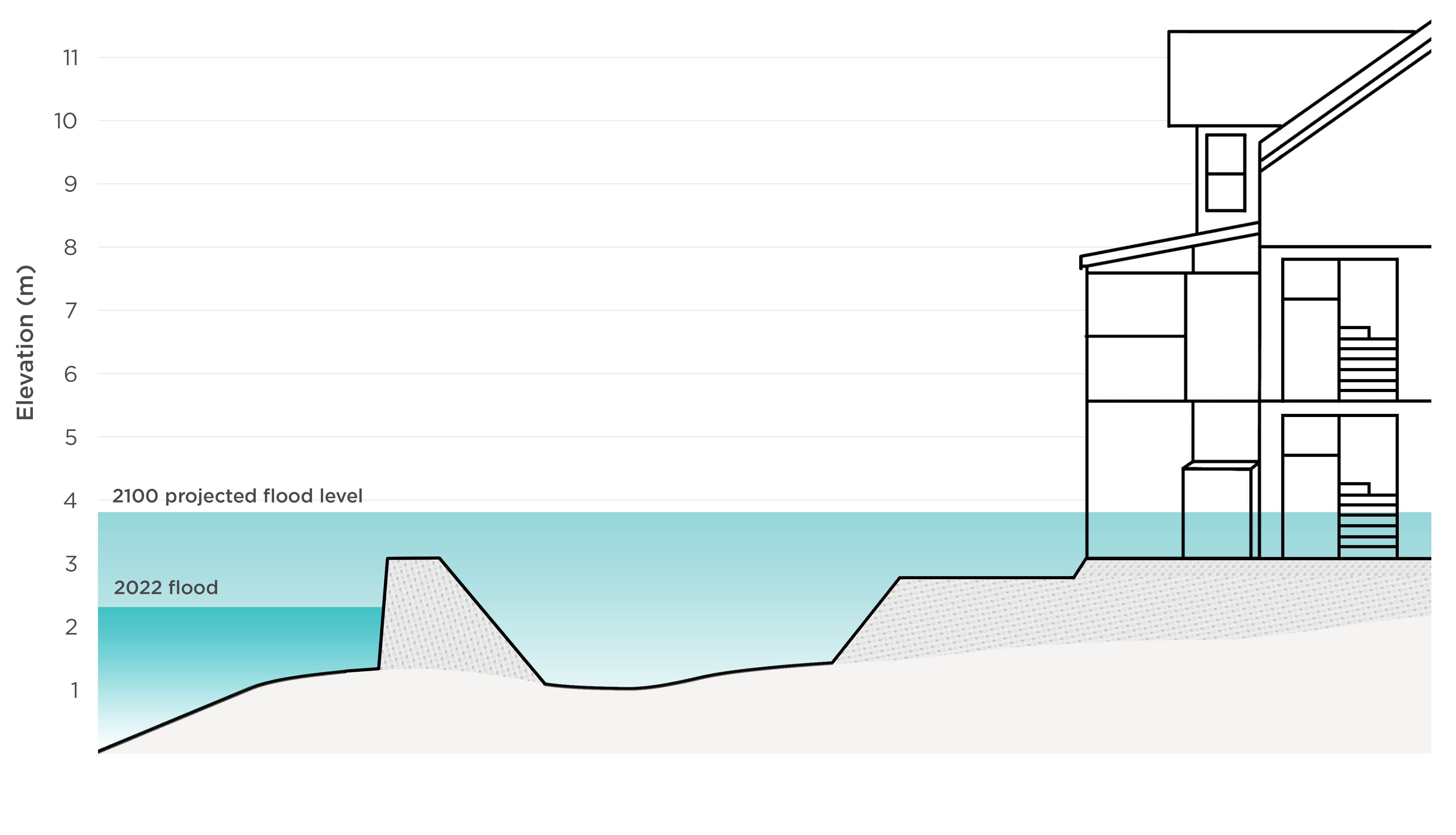

Also as at Rivervue, efforts were made at Kensington Banks to ensure homes would resist flooding.

A flood protection plan was drawn up by the Major Projects Unit based on estimates produced by Melbourne Water’s 1986 flood model.

The plan had three core elements:

- lowering flood levels by modifying a downstream bridge to allow water to flow more freely

- building a levee around the estate to keep flood water out

- including a safety buffer so floor levels at all homes would be at least 30 cm above the estimated flood level.

Land near the river was also excavated to increase flood storage and handle runoff from the estate, later becoming part of a common area known as Riverside Park.

A series of technical reports prepared by engineers engaged by the Major Projects Unit underpinned the plan (see ‘Arundel dam’ box below).

Flood modelling undertaken by the engineers claimed the combined effort would ‘virtually eliminate’ the risk of homes flooding.

The flood protection plan was later nominated for an engineering award, with promotional materials stating:

…flooding of the [Kensington Banks] site should now not occur any more frequently than once in 100 years. Predictions of frequency based on actual site levels is that the likelihood will be closer to once in 200 years.

Arundel dam rejected as a flood defence option |

A major 1986 Melbourne Water study into how to reduce flood risk along the Maribyrnong River recommended building a dam at Arundel, close to Melbourne airport. The report found a dam was the ‘preferred option’ to protect the whole catchment – including the future Kensington Banks site – from 1% AEP floods. However, the proposal had drawbacks. While Melbourne Water found no significant environmental blockers, the dam was expected to worsen flooding at Organ Pipes National Park. Building a dam at Arundel would also cost at least $16 million, and Melbourne Water lacked the necessary money. Critically, no level of government was prepared to fund the dam. In 1991, the Major Projects Unit studied flood protection options for the Kensington Banks site. It found a much cheaper option that it believed would deliver similar benefits to a dam at Arundel. It maintained that its solution would also protect Aboriginal cultural heritage sites, and avoid environmental effects such as erosion and wildlife disruption. From this report, the flood protection design at Kensington Banks took shape. Building water storage at Arundel is on a ‘long list’ of potential flood mitigation options for the Maribyrnong catchment, discussed later in the report. |

Flood levels lowered

Key to the design was lowering expected flood levels around Kensington Banks – necessary for the rest of the plan to work.

To do this, a downstream railway bridge that acted as a bottleneck was altered to allow more flood water to safely pass the Kensington Banks site.

The bridge modifications and related earthworks to increase flood storage were completed between 1992 and 1994 with funding from the Australian Government.

Flood modelling prepared afterwards showed the bridge works reduced flooding at the Kensington Banks site by 45 cm.

Remaining protection works were designed to deal with this lowered flood level.

Levee built around estate

The second core element of the protection plan was a flood-proof barrier around the development.

This involved building a levee along a 1.2 km stretch of the perimeter, made up of earth embankments, raised roads, and retaining walls. Its main purpose was to prevent flood waters entering the streets around homes.

Work on the levee started in 1994 and finished in about 2000, when most home building was also complete.

Homes built with safety buffer

The final element of the protection plan was a mandatory safety buffer for all homes.

This required floor levels at least 30 cm above the estimated flood level. It was achieved by filling and contouring the ground across the estate, then further raising floor levels as homes were built.

Figure 17 shows the combined flood protection works:

Figure 17: Kensington Banks flood protection works

Source: Victorian Ombudsman. Not to horizontal scale.

Climate change considered after most homes built |

Key to the flood protection plan was building all homes at least 30 cm above the flood level. This safety buffer was – and still is – required by the Building Regulations, and all homes at Kensington Banks included it. In 2000, with much of the estate finished, Melbourne Water asked that the safety buffer for remaining unbuilt homes at Kensington Banks be increased to 60 cm. It sought the change due to, among other things, the risk of higher floods in future due to ‘implications associated with the greenhouse effect’. This was the first and only consideration of climate change we identified in the development of Kensington Banks. Climate change at that time was an emerging concept, with a focus largely on rising sea levels rather than river floodplain effects. The 1986 Australian Rainfall and Runoff edition then in use noted the topic was receiving increasing scientific attention, but that no reliable estimates of its effects were yet available. Its modelling guidance assumed that rainfall and floods remained constant throughout the design life of projects. Plans later submitted by the developer included a 50 cm safety buffer for the final set of Kensington Banks homes – higher than the originally approved plans, though slightly lower than Melbourne Water’s updated preference. Melbourne Water now typically requires a minimum 60 cm safety buffer when developing in river floodplains (as occurred in the case of Rivervue). |

Flood planning controls removed

During much of its development, most of Kensington Banks was covered by a type of planning control that no longer exists, known as a Floodway Management Area (‘FMA’).

Development in these controlled areas was not banned, but triggered a referral to Melbourne Water.

The former FMA was a major point of friction. The Major Projects Unit was keen for the planning control to be removed from the start, but Melbourne Water insisted it remain until all works were complete.

Privately, the Major Projects Unit worried it would make land undesirable to developers and possibly ‘difficult to sell’.

After long negotiations, Melbourne Water agreed in principle to removal of the control in stages, once satisfied each area was protected from flooding.

This involved:

- reviewing certified survey plans to confirm the height of levee banks and site fill

- testing for soil compaction issues

- constructing additional, temporary levees around land yet to be developed.

Most of Kensington Banks was then removed from the former FMA (which also converted into an LSIO) through a series of planning scheme amendments spanning 1994 to 2001.

Removal of the planning control did not materially alter home design at Kensington Banks, as flood protection works and development plans were by that point already in place.

Afterwards, Melbourne Water continued to check and enforce floor level requirements, withholding other approvals until it was satisfied homes were above the flood level.

Figure 18: Flood overlay in planning scheme, before development

Source: Victorian Ombudsman

Figure 19: Flood overlay in planning schemes, after development

Source: Victorian Ombudsman

Problems exposed by 2024 flood modelling

Figure 20: What we heard from Kensington Banks residents

Source: Submissions to the Victorian Ombudsman

The first major test of the flood defences at Kensington Banks was the October 2022 flood. The estate’s barriers – designed to protect the site from a more severe event – largely worked as intended.

But in 2024, Melbourne Water completed a new flood model for the Maribyrnong catchment , the first major update in more than 20 years.

Despite the extensive efforts to protect the site, the new model flagged most of Kensington Banks as at risk of future flooding.

Figure 21: Estimated 1% AEP flood extent at Kensington Banks

Source: Victorian Ombudsman, based on 2024 modelling for Melbourne Water

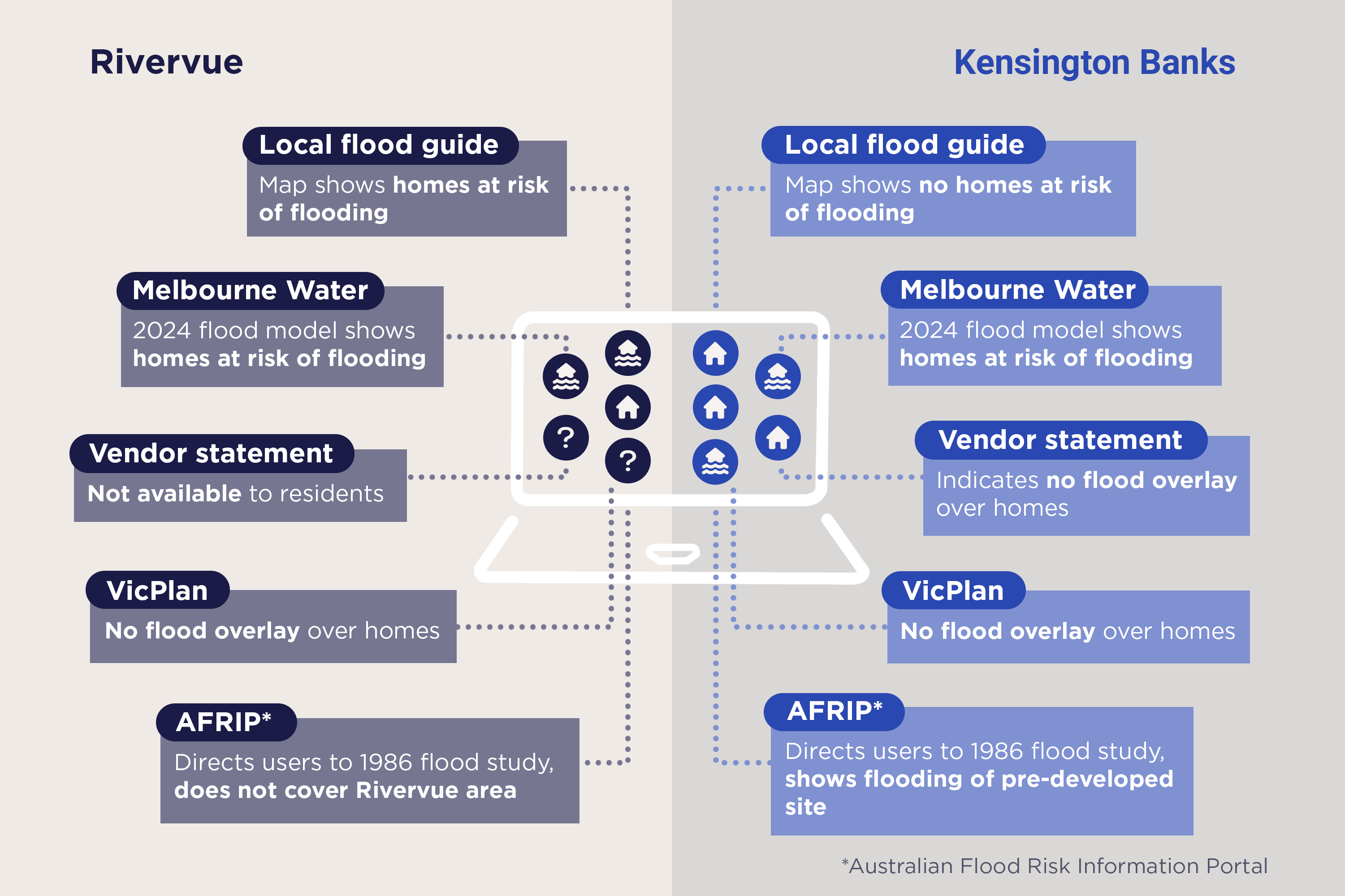

For residents, this was a complete shock. Official information available to them when buying homes had indicated a ‘flood free’ status.

All wanted to know why flood protection works at the government-backed development – designed just 30 years earlier to ‘virtually eliminate’ flood risk – had fallen short of their aim.

Many also wanted to know why they first learnt about this new flood status via news media, or a neighbour.

Though Melbourne Water scheduled letter box bulletins, webinars, and community drop-in sessions, many residents still complained of poor communication about the updated model and what it meant for their home.

| Case study 2: Long-term resident still coming to grips with shocking news | |

| Carol had considered her Kensington Banks home a ‘safe haven’ for more than 20 years. The former public servant bought her townhouse in 2005, and was among early residents to call the award-winning urban renewal project home. She told us she was drawn to the development’s village feel, beautiful gardens and its modern buildings set among relics of the area’s stockyard past. But Carol’s strong connection to and satisfaction with her surroundings began to shift when the Maribyrnong flooded in October 2022, offering the first glimpse of an unwelcome future. ‘I spent most of that day walking around my neighbourhood. I was shocked the Maribyrnong River had broken its banks and was increasingly lapping up the side of the levee bank that Kensington Banks houses are constructed on,’ she says. Though no water entered her property that day, she felt disturbed and distressed that ‘if the river kept rising, I would be on my own dealing with something way out of my league’. Carol says a media article in May 2024 brought a fresh new shock that she is still grappling with. ‘I was enjoying breakfast and browsing the day’s newspaper until I turned the page and read the article announcing Melbourne Water was rezoning Kensington Banks,’ Carol says. Carol told us of the significant personal impact the revelation she now lived in a flood prone area has and will continue to have. Before, her plan was to live in her home ‘until my knees give out on the stairs’. Now, she says, ‘that plan has evaporated’ and she feels ‘stuck’. Carol told us she felt information she’d since received from Melbourne Water had ‘not explained in anything close to plain English’ about the change and the basis for it. She does not consider various public communication efforts by Melbourne Water – including letter box drops and drop-in sessions – have yet done enough to inform owners and residents, and says some of her direct requests for specific information have gone unanswered. Carol told us that, overall, she feels unsupported by Melbourne Water and the Victorian Government, and is ‘frustrated, anxious, depressed, confused, lost and no better off knowledge, learning or action-wise than I was when I read the newspaper over breakfast that fateful day in May 2024’. |

In a submission, Melbourne Water acknowledged it did not have enough time to sensitively notify affected households.

It said the model was developed and released to a ‘strict deadline’ dictated by two major reviews into the October 2022 floods.

The updated modelling was a key input for Melbourne Water’s independent review which reported in April 2024 on the flood impacts of the Flemington Racecourse wall. The modelling also helped Melbourne Water have answers ready in time for Parliamentary Committee hearings in May 2024.

The Victorian Flood Data and Mapping Guidelines say flood modelling should be done ‘in consultation with local communities to make use of local knowledge’. This should include public meetings and discussion with affected landowners.

Yet the rush to complete the new model meant there was effectively no scope for residents or other interested parties to learn about and contribute to its development.

This meant people looking to buy property in Kensington Banks were unaware that new flood modelling was underway, and could not factor this into their decision.

The hasty release of the new model also contributed to a lack of property-specific details being given to residents. Initial flood maps showed only the extent of expected flooding – not the predicted depth. This had the potential to cause alarm. Melbourne Water later released detailed flood depth maps.

We discuss some other impacts residents are still coming to grips with now they better understand their flood risk in the next chapter.

Why did the flood status change?

The release of new flood maps left many residents asking why flood protection works at Kensington Banks no longer appeared to be working.

The short answer is that estimated flood levels at Kensington Banks are now higher than when the development was planned.

There is no single reason for this late discovery. However, we identified four potential contributing factors:

- Changes to catchment conditions: works were designed for conditions in the early 1990s, and did not predict flooding increases caused by urban creep and climate change.

- Flawed historic modelling: long gaps between model updates and questionable techniques may have cost chances to spot the first signs of trouble.

- An improved flood model: the new flood model is more sophisticated than previous ones, and processes a lot more data.

- Levee settlement: the flood protection levee around Kensington Banks appears to have sunk in places and may no longer be as effective.

Changed catchment conditions

Kensington Banks was designed to handle flooding at levels taken from Melbourne Water’s 1986 flood model.

This model used good flood modelling techniques for its time, and provided a solid basis for assessing flood risk at the site.

Yet catchment conditions have changed over the past 40 years. The area along the river is more developed, and climate change is likely altering rainfall patterns.

These considerations were not top of mind as Kensington Banks took shape. Future growth and possible climate shifts were broadly recognised in flood guidelines, but not actively factored into flood models of the time.

The Kensington Banks flood protection plan essentially assumed that catchment conditions would stay the same. This reflected the approach of the time, but is no longer considered good practice.

| Urban creep and climate change increase flood risk | |

| Urban creep can have major impacts on flooding, with new buildings and other construction changing how water behaves. Harder surfaces prevent rain from being absorbed into the ground. This leads to more runoff and, in turn, higher and more frequent floods. Climate change is also a known driver of flood risk. As the climate warms, more atmospheric water vapour causes more intense rainfall, leading to more frequent and severe flooding. According to Victoria’s Climate Science Report 2024, ‘small floods are becoming smaller and large floods are becoming larger’. Over the past 50-70 years Victoria has seen:

These trends are expected to become more striking in future. If greenhouse emissions continue to rise at current rates, flood risk in Victoria is expected to double by 2100. |

Flawed historic modelling

Melbourne Water’s past approach to flood modelling may mean that earlier opportunities to reassess flood risk were missed.

There were long gaps between models, and we identified shortcomings in the 2003 lower model prepared while Kensington Banks was nearing completion.

Model not regularly updated

There is no fixed interval for updating flood models, though it has recently become generally accepted they should be revised every 5 to 10 years – with highly urbanised catchments at the lower end of this range.

The intervals between Melbourne Water’s flood models for the Maribyrnong catchment were 17 and 21 years. This meant modelling was not kept properly up to date with changes in the catchment and other new data.

Melbourne Water has accepted a recommendation from the Maribyrnong River Flood Event Independent Review to review its flood levels every five years and update them every 10, or after a significant flood.

Model has shortcomings

The issue of long gaps between models was compounded by some shortcomings with the 2003 lower model when it was eventually prepared.

Its original purpose was to help Melbourne Water assess potential impacts of the Flemington Racecourse wall.

The 2003 lower model covered a similar area to the 1986 model, but took into account catchment changes over the years between models – including at the near-complete Kensington Banks.