Councils and complaints - a good practice guide 2nd edition

Date posted:This updated guide provides advice on implementing new legislative requirements relating to complaints, using good practice complaint handling and building a positive culture around complaints. It includes practical tools including templates, real examples and a self-assessment tool for councils.

Introduction

Councils are an integral part of Victorians’ lives. They provide community services; manage recreation facilities; construct and maintain local roads and essential infrastructure; support business and economic development; regulate planning and land use; and enforce various State and Federal laws.

Purpose of this Guide

Of the three tiers of government, Councils often have the most direct contact with the public. It is unsurprising that Councils deal with high numbers of complaints. Complaints are ‘free feedback’ for Councils about their services and can highlight needs for improvement1. The new Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) (‘the 2020 Act’) now requires Councils to have a complaints policy and process2.

We have a developed this standalone guide to help Victorian Councils to deal with complaints.

Complaint handling is core business for Councils.

There is no single effective approach to managing complaints.

A complaint handling system is the sum of many parts – legislative requirements; executive leadership and organisational culture; case and data management systems; and training and support for staff. Different combinations of these parts will work better in different contexts.

This Guide aims to provide practical advice for building a positive culture around complaints and good complaint handling practices and systems that can be adapted to suit local contexts.

The Guide looks at the elements of a good complaint handling system, and uses real examples so that Councils can learn from one another. Other service sectors can also benefit from the Guide.

We use symbols in the Guide to show:

History of the Guide

The Ombudsman first published a ‘good practice guide’ for Councils in February 2015. This accompanied Councils and complaints – A report on current practices and issues which looked at complaint handling practices across all 79 Councils.

Five years later, the Ombudsman re-examined Councils’ complaint handling practices in the 2019 Revisiting Councils and complaints report. We noted that Councils had, by and large, improved their complaint handling processes. But we identified inconsistencies between Councils, including how they define and record a ‘complaint’. We also found there were still some areas of complaint handling that could benefit from attention.

The Ombudsman made recommendations to the Minister for Local Government and Local Government Victoria to improve the sector’s approach to complaints. These took effect in the 2020 Act. The Ombudsman’s recommendation for public reporting of Councils’ operations and performance will be introduced through subordinate Regulations.

At the same time, the Ombudsman undertook to update the 2015 Guide.

Structure of the Guide

This 2021 Guide is structured around three basic concepts of good complaint handling. The three concepts are recognised under Australia/ New Zealand standards3, and are implicit in International standards4. They are:

At the end of the Guide, we include the following resources for Councils to use and adapt:

- Appendix A: Additional resources

- Appendix B: Model complaints policy for Councils

- Appendix C: Self-assessment tool for Councils

- Appendix D: Model wording for written outcomes to investigations

What is a ‘complaint’?

The 2020 Act defines ‘complaint’ (section 107(3)):

For the purposes of the complaints policy, complaint includes the communication, whether orally or in writing, to the Council by a person of their dissatisfaction with –

(a) the quality of an action taken, decision made or service provided by a member of Council staff or a contractor engaged by the Council; or

(b) the delay by a member of Council staff or a contractor engaged by the Council in taking an action, making a decision or providing a service; or

(c) a policy or decision made by a Council or a member of Council staff or a contractor.

This definition aligns with the Australian/New Zealand Standard definition.5

In simple terms, a complaint to a Council is any communication which involves the following:

- an expression of dissatisfaction

- about an action, decision, policy or service

- that relates to Council staff, including the CEO, a Council contractor, or the Council as a decision-making body (not individual Councillors, who are subject to different processes).

The definition of complaint does not take into account:

- the merit of the complaint or issue complained about

- how the matter will be resolved or responded to

- the complainant’s motivations.

Supporting a broad definition of ‘complaint’: Warrnambool City Council

Warrnambool City Council’s Feedback and Complaints Resolution Centre brochure defines a complaint consistently with the Local Government Act definition.

What is a Complaint?

You may make a complaint if you are dissatisfied with the service we provide or when we have failed to comply with our policies or procedures. You can also make a complaint if we may be liable for property damage or loss, or you are unhappy by the actions of Council (representatives, employees or contractors) including allegations of misconduct or abuse.

Source: Warrnambool City Council, Contact Us - Feedback and Complaints Resolution Centre

Complaints about individual Councillors

The 2020 Act’s definition of ‘complaint’ does not include complaints about Councillors.

Councillor conduct is dealt with in another part of the Act (Part VI). Councils must have processes in place to manage complaints about Councillors. These should set out:

- information about your Council’s Councillor Code of Conduct

- what Council staff and Councillors do if they receive a complaint about a Councillor

- roles of the Council’s CEO and Mayor in managing complaints about Councillors

- a pathway for complaints to be referred to a Councillor, group of Councillors or the Council, to consider if an application for internal arbitration should be initiated6

- processes for engaging internal or external investigators

- information about how people can complain to the Local Government Inspectorate and the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (‘IBAC’).

‘Complaint’ versus ‘service request’

The Ombudsman’s 2019 Revisiting Councils and complaints report noted that Councils classified complaints and service requests inconsistently.

Differentiating between a ‘complaint’ and ‘service request’ may not seem important if the problem is fixed. However, if Councils do not properly record complaints, they cannot accurately measure their performance and use that information to improve services.

One way to distinguish a service request from a complaint is to look at whether a person is:

- requesting something additional or new (a service request)

- reporting what they believe to be a failing or a shortfall (a complaint)

- complaining about a Council’s response to a service request (a complaint).

Table 1: Complaint/Service request examples

| Complaint | Service request |

| My bin was out but wasn’t collected this morning. Can you pick it up? (complaining that the Council didn’t provide a service) | I forgot to put my bin out, can someone collect it? (requesting a service because of their own mistake) |

| You haven’t sent out my rates notice. | Can you tell me when my next rates payment is due? |

| The Council shouldn’t have approved a development on Main Road. | What is the process for objecting to the development on Main Road? |

| The Council’s website doesn’t have enough information about when a planning permit is needed for a pool. | Can you tell me whether a planning permit is required for a backyard pool? |

| Council’s investigation into noise from a business wasn’t rigorous, and didn’t look at peak times. More investigation is needed. | My neighbour’s business is very noisy. Can you make it stop? |

| A pothole I reported to Council two months ago hasn’t been fixed, and is getting worse. | Could Council fill in a pothole in my street? |

A complaint may lead to a service request being lodged. For example, a complaint about a missed bin might result in a service request for the bin to be collected – however, it should still be counted as a complaint.

Recording a 'complaint' as a 'service request'

Some Councils tell us:

- When residents say their bins have not been collected, the Council sees this as a ‘service request’ and not a ‘complaint’.

- Residents often fail to put their bins out prior to collection, and then contact the Council to falsely report that the collection didn’t happen.

- Recording this as a complaint misrepresents what the Council believes, and can sometimes prove, to be false.

This approach raises a number of issues:

- It fails to take the complaint at face value, and makes an assumption about the complainant’s motivation.

- It is not consistent with the 2020 Act’s definition of ‘complaint’.

- Councils commit to providing services such as rubbish collection. If that service is not provided, people have the right to complain.

- It misses an opportunity to identify potentially systemic problems with the bin collection service.

- It obscures the fact that the Council might be responding to and resolving these complaints.

The 2020 Act implies complaints should be taken at face value. Describing a ‘complaint’ as a ‘service request’ undermines data collection and analysis. Opportunities to improve customer service will be missed.

1. Enabling complaints

Enabling people to complain is not just about making it easy for a person to lodge a complaint. The concept includes a reasonable assumption that members of the public expect that when they complain, their Council will properly consider and respond to their concerns. This can only be achieved through a combination of established systems for receiving and managing complaints, and a positive organisational culture that sees complaints in a constructive light.

Councils can enable complaints by:

1.1 fostering a collective commitment to complaint handling

1.2 applying a consistent, Council-wide approach to complaint handling

1.3 creating transparent processes and publicising ‘how to complain’

1.4 ensuring the complaint process is accessible and easy to understand.

Making a strong statement of commitment: Mansfield Shire Council

Mansfield Shire Council publishes information about complaints in its Customer Service Charter. This includes a broad definition of a complaint, a positive perspective on the value of complaints, and information about where people can find more information about the Council’s complaint process.

Complaints

If you are not entirely satisfied with the service you have received from Council, or you wish to air a concern, you are invited to put your complaint in writing and forward to Council.

Council welcomes feedback and sees it as an opportunity to improve its service to the community. Council continues to monitor its performance and aims to improve as much as possible.

Your written complaints, concerns or feedback can be posted to:

Mansfield Shire Council Private Bag 1000, Mansfield, VIC 3722

Or emailed to: council@mansfield.vic.gov.au

Wherever possible, Council will aim to resolve a customer’s complaint at the customer’s first point of contact with Council. All complaints received are managed in accordance with Council’s Complaint Resolution Policy and Procedure.

1.1 Fostering a collective commitment to complaint handling

Committing to complaint handling means welcoming complaints as ‘free feedback’. This means being interested to find out what complainants are telling your Council about its services, and acting to resolve their concerns at an individual and systemic level.

All Council staff, including contractors and Councillors have a role to play.

Leaders and managers set a positive tone by:

- talking with staff about the benefits of complaints

- appointing frontline staff who are skilled in customer service

- ensuring all staff who deal with complaints have adequate training and support

- delegating authority to staff to make decisions to resolve complaints

- establishing processes for analysing and reporting complaint data, and acting on trends.

All Council staff, including contractors, and Councillors contribute to a culture that is receptive to complaints, by:

- familiarising themselves with their Council’s complaints policy and process

- helping people to complain and to understand the complaint process

- treating members of the public respectfully and professionally. Councils can increase awareness of the complaint process by including it in induction programs and regular refresher training.

Skilled customer service and complaint handling officers

Skilled complaint handlers rely on technical expertise and interpersonal skills to resolve complaints, and will have or develop the following attributes:

Technical expertise

- understanding Council’s services and complaint process

- ability to solve problems

- case and time management

- ability to act impartially and fairly.

Personal qualities

- empathy and patience

- ability to adapt communication to suit different people

- resilience.

Dealing with complaints can be difficult and tiring. Complaint handlers need support to maintain a positive attitude to their work. This can be provided through:

- guidance materials and a functioning complaint management system

- training in good decision making and in responding to challenging behaviour by complainants

- debriefing with a manager or other staff, and access to employee assistance programs and professional support.

1.2 Applying a consistent, Council-wide approach to complaint handling

An established consistent process for complaints helps both Council officers and the public understand what to expect. Your Council’s complaints policy must7, at a minimum, set out steps for:

- dealing with complaints

- conducting internal reviews

- deciding when to refuse to deal with a complaint because it is otherwise subject to review under other legislation.

The discretion to refuse to deal with a complaint which is otherwise subject to statutory review

The 2020 Act gives Councils a discretion to refuse to deal with complaints that can otherwise go through a statutory review process.8

This means complaints where there is a review or appeal to a tribunal, eg the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (‘VCAT’) or a court, under an Act or regulation. Complaints of this type usually concern a particular subject matter, such as infringements, planning, or public health.

Councils can still deal with these complaints through their general complaints process. However, the discretion ensures the supremacy of statutory review processes in most cases.

Council’s reasons for refusing to deal with a complaint which is otherwise subject to statutory review might include:

- the statutory review process is already underway

- it is reasonable in the circumstances to expect the complainant to go through that review process

- a tribunal or court will settle or determine the matter faster

- the complaint relates to a specialised area, and it is proper that a tribunal or court make a binding determination on the matter (noting the determination’s possible precedential effect).

Where the discretion to refuse these complaints is exercised, Councils provide their reasons.

Councils can also decide not to exercise this discretion. In some circumstances, it can be better for both the Council and complainant to deal with a complaint outside the statutory review process. An example is where a satisfactory resolution can be achieved faster and at lower cost.

A Council decision not to exercise the discretion does not waive the complainant’s right to access the statutory review process.

A complete complaints policy covers the full life-cycle of a complaint, including:

- how and when a complaint can be made

- who is responsible for managing the complaint as it moves through different processes (eg triage, investigation, remedy)

- expected response times

- references to related processes or policies (such as a public interest disclosure procedure)

- how complaint data will be stored and used

- avenues of internal and external review.

Each Council can tailor its policy to suit its capacity and the needs of its community. For example, a large Council with a dedicated complaint or customer services team will have different processes from a small Council where complaints are dealt with by a manager of the relevant area.

A model complaints policy for Councils is provided at Appendix B.

When a Councillor receives a complaint

Councillors are often the ‘face’ of their Council. Residents can see them as a having the means and power to fix Council’s problems. As a result, Councillors do receive complaints from their constituents. But often their role in handling these complaints is misunderstood.

Setting out steps in your Council’s complaint handling procedures will help both Councillors and Council staff manage complaints consistently. For Councillors, these steps include:

- referring complaints about Council operations to the CEO or a designated officer

- writing to the complainant to tell them their complaint has been referred to Council administration for response

- following protocols for interacting with Council staff.9 These include not seeking to influence or direct Council staff on how to deal with a complaint.10

Council staff dealing with a complaint referred from a Councillor:

- deal with the complaint in accordance with the Council’s complaints policy

- communicate with the complainant, including providing and signing the response

- inform the Councillor of the outcome, after the complaint is finalised.

Complaints about the CEO, decisions at Council meetings and contractors

There are some people and decisions in Councils that stand outside usual oversight and reporting lines – the CEO, Council contractors and decisions made at Council meetings. Councils should develop specific procedures for managing complaints about the CEO, Council contractors and decisions made at Council meetings, such as:

- where the complaint should be directed

- who will deal with the complaint and in what circumstances

- what measures are in place to protect the integrity of any investigation

- how to document the complaint process and the outcome

- how a complainant can access an internal review

- when complaints might be referred to the Local Government Inspectorate, the Victorian Ombudsman or IBAC.

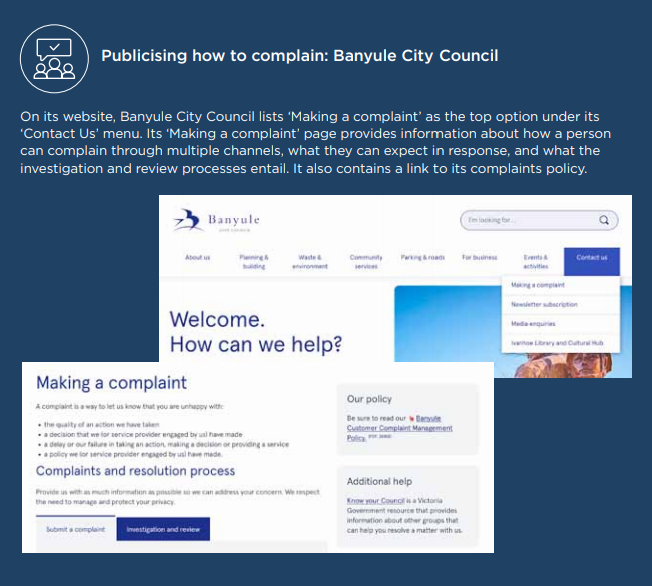

1.3 Creating transparent processes and publicising how to complain

Council transparency ensures accountability and creates public trust. A transparent complaint process means people know what to expect when they complain.

Your Council can make it easy for people to complain by publishing information about how to complain and your complaint process. Simple steps include:

- publishing your complaints policy on your website,11 and making it available in hard copy

- making sure your website’s search function leads people to your complaints policy and related information when a person keys in ‘complain’, ‘complaint’ or ‘complaints’

- including a prominent link on your homepage, or contact page, to information about making a complaint

- providing information on your website about common complaints, and how they might be resolved.

Source: Banyule City Council, Home - Contact Us

1.4 Ensuring the complaint process is accessible and easy to understand

Some people face barriers to complaining, such as trouble speaking English, having a disability, being homeless or being employed in shift work. A person’s age, level of literacy, cultural background or personal circumstances may also influence how they contact the Council.

State and Federal laws protect individuals in certain circumstances from discrimination based on a ‘personal attribute’ – even where the discrimination occurs unintentionally. These laws also place a positive duty on organisations, including Councils, to eliminate discrimination and take reasonable steps to enable people to access and participate in services.12

Victorian Councils must also act in a way that is compatible with a person’s human rights.13 In relation to complaints, this can be achieved by ensuring a person can engage meaningfully with the Council.

Your Council can promote accessibility by:

- accepting complaints through multiple channels, including telephone, letter, email, online and in person

- offering free access to a translation and interpreter services

- using the National Relay Service, communication boards, Auslan interpreter services and other aids to communicate with people with hearing or speech difficulties

- providing information in accessible formats14

- using text to speech web functionality (websites that work with specialised software that reads the text aloud)

- providing fact sheets in Easy English, which combines short, simple sentences with pictures for people who have difficulty reading

- actively helping people to complain, if needed

- offering ‘reasonable adjustments’ to complainants to assist them to communicate with Council and access Council’s services15

- accepting complaints from an authorised third person if a person has trouble complaining.

Test the success of your system by comparing your Council’s community profile with the people who complain. This can help find out whether some groups are under-represented.

Ways to improve engagement with under-represented groups include connecting with community leaders and advocacy groups, or consulting community services such as schools, clubs, and places of worship.

Source: Maroondah City Council, Contact Us - Easy English

2. Responding to complaints

Responding effectively to complaints involves investing time and resources. While the benefits may not be immediately evident, recent research shows it can increase public trust, staff productivity and wellbeing, and compliance with the Council’s laws and processes. This in turn can lower Council costs.16

Although there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to responding to complaints, effective complaint handling processes have the following elements:

2.1 Timeliness

2.2 Triage and initial assessment

2.3 Tiered approach to managing complaints

2.4 Explaining complaint processes to manage expectations

2.5 Treating complaints fairly

2.6 Evidence-based and objective decision making

2.7 Communicating outcomes effectively

2.8 Confidentiality and privacy

2.9 Providing internal and external review options

2.1 Timeliness

Timely communication with members of the public is a cornerstone of a responsive complaints system.

Timeliness can also influence a person’s perception of fairness and their satisfaction.17 Delays can frustrate people, particularly where penalties or interest continue to build while the complaint is being considered. Delays can also lead people to escalate complaints to the Ombudsman or other oversight bodies.

Set clear timeframes for contacting complainants during the complaint process, such as:

- acknowledging the complaint within five business days (some complaints may be acknowledged even faster eg online complaints may be acknowledged immediately through automated processes, and voicemail messages can be returned within two business days)

- providing Council’s decision within 30 calendar days

- advising if the response will take longer, and updating the complainant at least every 30 calendar days

- applying the same timeframes to the internal review process.

Source: Whitehorse City Council, Contact Us - Customer Service Charter

Why acknowledging complaints is important

Acknowledging a complaint is a statement of commitment. It confirms receipt of the complaint, but also says to the complainant that a Council officer will take time to consider their concerns and respond. It is often a person’s introduction to the complaint process, and can set the tone for future contact. The best acknowledgements explain what will happen next and by when, and who to contact with further queries. It is helpful to provide a reference number.

Model wording for a tailored written acknowledgement

Dear …

Thank you for your email about [describe what it is about, eg works to repair the footpath on High Street]. Your complaint reference number is 21/2341.

We are currently assessing your complaint and will contact you again by [date] to give you an update.

If you have any questions in the meantime, please contact [name of responsible officer] on [direct email and/or telephone contact details].

Yours sincerely

...

2.2 Triage and initial assessment

Resources available to Councils are finite. Early assessment of a complaint helps Councils prioritise and allocate resources fairly. It is also the most efficient way of producing a prompt and proportionate response for every complaint.

A triage process looks at what the complaint is about, and determines how, who and when to respond. It takes into account the seriousness and urgency of the issues and the risks. Factors to consider when triaging complaints include:

- What is the complaint about? Some complaints can be dealt with quickly, whereas others may need expert consideration.

- Is there any urgency, such as an immediate risk to the safety or wellbeing of a person, or security of property?

- How serious or complex are the issues?

- Does the complainant have communication needs or personal circumstances that require careful management?

- Are there statutory processes that must be followed? eg complaints about infringements through the review processes under the Infringements Act 2006 (Vic).

- Should the complaint be handled by an independent person? It may be more appropriate for an independent officer to deal with it to manage any perceived bias.

- Does the complaint indicate a systemic failing which might affect the broader community?

- What are the prospects of meaningfully investigating or resolving the complaint? The issues may be too old, the person complaining may not be directly affected, or they may want a resolution that Council cannot achieve. There may be a different, more relevant, complaint process available to the person.

If more information is needed to triage the complaint, contact the complainant to clarify their complaint and find out what outcome they are seeking.

Model for triaging complaints: Keep, Transfer or Decline

The ‘Keep’, ‘Transfer’ or ‘Decline’ model can be used as a framework for triaging complaints. In this model, frontline line staff are delegated to decide whether to:

- Keep and resolve the complaint. This requires triage officers to have the necessary delegation to resolve the complaint.

Example: A customer service officer ‘keeps’ a complaint about a missed bin because they can resolve the complaint - by lodging a service request on behalf of the complainant. - Transfer the complaint to a particular team or person, if it requires specialist expertise, advice or investigation.

Example: A customer service officer ‘transfers’ a complaint about lack of enforcement action in relation to a business’s overflowing rubbish bins to the Council’s Public Health Unit, because it has the expertise to investigate and provide advice to the complainant. - Decline the complaint if there is a more appropriate pathway the complainant should use.

Example: A customer service officer declines a complaint from an objector to the Council’s decision to grant a planning permit, because they have a right of statutory review at VCAT.

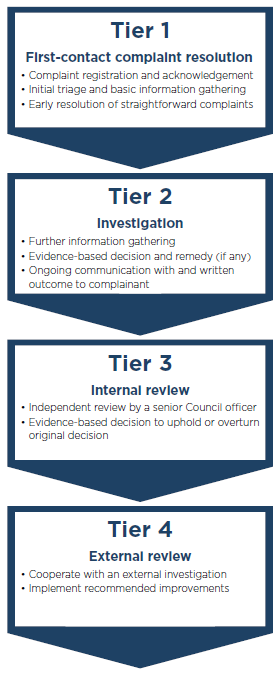

2.3 A tiered approach to managing complaints

A tiered approach to managing complaints provides a pathway for a complaint, with each tier representing an escalation point. The Ombudsman recommends a four-tier model:

Tier 1: First-contact complaint resolution

The aim of tier 1 is to resolve most complaints at the time a person first contacts your Council – through quick and mutually acceptable solutions. It relies on complaint handlers having the necessary skills to understand the complaint and the power to create a solution. If a solution cannot be immediately found, then the officer needs to be able to explain what will happen next, and why.

Tier 2: Investigation (if required)

If a complaint needs further consideration, it moves to tier 2. An investigation is usually carried out by an officer with specialist expertise. They gather additional information and make an evidence-based decision. Generally, they will communicate with the complainant throughout the investigation, and provide a written outcome that explains the Council’s decision.

Tier 3: Internal review

If a complainant believes the Council has made a wrong decision, they can request an internal review. This moves the complaint to tier 3. A senior officer conducts an independent internal review and looks at whether the complaint should have been dealt with differently. This can lead to the original decision being upheld or overturned.

Tier 4: External review

Where a complainant still believes your Council has made a wrong decision, provide information about how to seek an external review. Tier 4 generally involves a complaint being escalated to an oversight body such as the Ombudsman or the Local Government Inspectorate, or to a tribunal or court. Councils contribute to tier 4 by participating in and cooperating with the external review process.

Figure 1: Four-tier model for complaint management

When is a complaint ’resolved’?

It is not always possible to resolve complaints to the satisfaction of the complainant. Councils are bound by legislation and the public interest when identifying a remedy to a complaint.

For Councils, a complaint can be ‘resolved’ where:

- the complainant is satisfied with the action taken by the Council

- the issue identified by the complainant has been fixed

- further action is unnecessary and unjustifiable because reaching a mutually agreeable solution would disproportionately consume Council resources, and/or

- the Council is confident that should their response to a complaint be considered through an external review, it would likely be upheld.

2.4 Explaining complaint processes to manage expectations

Explaining your Council’s role and complaint process at the outset helps people understand how their complaint will be handled. This manages their expectations.

When a person contacts their Council, they may expect an instant response or feel entitled to get what they want as a resident or ratepayer. They may also have unrealistic views about the remedies you can provide, such as compensation or having someone fired.

When explaining your complaint process, communicate:

- Council’s role in relation to the issues

- what issues you will and will not be considering

- what you will do to consider the complaint

- how the complainant will be involved in the complaint process • expected timeframes for a response

- possible or likely outcomes.

2.5 Treating complaints fairly

Fairness in complaint handling involves giving people an opportunity to be heard and responding to their complaint in an even-handed way. Councils can build fair systems through transparent processes, acting without bias or a conflict of interest, and protecting people from detriment when they complain.

Fairness is further promoted by:

- giving people sufficient opportunity to present their view

- making sure you properly consider, understand and engage with the concerns • assessing any new issues

- deferring associated decisions, such as regulatory or enforcement action, until the complaint is finalised.

If someone complains about a Council officer, that officer is also entitled to be treated fairly. Subject to any legislative restrictions such as those in the Public Interest Disclosures Act 2012 (Vic), Councils:

- inform the officer of the complaint

- give the officer an opportunity to respond

- keep the officer informed of progress of any investigation and the final result, with reasons.

The focus of the complaint handling process is about resolving the problem, and continuous improvement.

If the Council determines that a disciplinary process is warranted, it should be dealt with separately from the complaint handling process.

2.6 Evidence-based and objective decision making

Relying on evidence and exercising objectivity are also essential to a fair complaint handling process.

While all investigations are a fact-finding process, they can vary depending on:

- the seriousness and extent of the issues

- the availability of relevant information or evidence

- the degree of certainty required to determine what action (if any) to take

- the outcome sought and potential for a satisfactory resolution.

Every investigation involves:

- Considering the complaint impartially. Conflicts of interest must be avoided, or declared and managed to remove any actual or perceived bias.

- Gathering information from a range of sources. This commonly includes the complainant and Council systems or resources. Information may also be sourced from Council staff, experts, third parties and external resources.

- Critically analysing the evidence. Take into account the different perspectives, and the reliability and relevance of the information. Then decide whether, on balance, the evidence tends to support the complaint or not.

- Examining not only whether the Council followed legislation or policy, but also whether its actions were fair and reasonable.

- Focussing on whether a solution can be reached. • Forming conclusions that are rational and logical, supported by evidence and reasons, and can stand up to external scrutiny.

- Keeping good records of what was investigated, the steps taken in the investigation, the evidence, decisions and associated reasons, and any remedial action.

The nature of an investigation will vary. For example, an investigation of a complaint about the Council not repairing a pothole may look at the Council’s service request and road maintenance logs, and involve a site inspection. However, a complaint about a Council officer behaving inappropriately may involve appointing an independent investigator to interview witnesses and staff, review CCTV footage and incident reports, obtain legal and HR advice and prepare a formal investigation report.

Finding a solution

When attempting to find a solution, your Council can look beyond what the complainant says they want, to what action would be practical and proportionate.

Solutions may be:

- providing a better explanation for the Council’s decision or actions

- reversing a decision

- acknowledging and apologising for an error, and explaining what the Council is doing to prevent it from happening again

- providing redress, through an ex gratia payment as a gesture of goodwill, or compensation where appropriate.

2.7 Communicating outcomes effectively

Often an outcome to a complaint is best communicated through a conversation. Conversations gives complainants an opportunity to ask further questions. They also give the complaint handler a chance to check they have not misunderstood or overlooked important parts of the complaint.

Where the Council has conducted a substantial assessment or investigation, provide the outcome in writing. A written outcome sets out how the decision was reached, as well as what the Council or complainant can do next. However, it is almost always helpful to have a conversation first.

This ‘foreshadowing’ conversation can ensure disagreements are addressed before the complaint is finalised. They make it less likely that the complainant will escalate the matter further. A written outcome should:

- use plain English, and avoid bureaucratic jargon

- explain the steps the Council took to investigate or resolve the complaint

- state the relevant evidence and conclusions of the investigation, and set out the reasons

- openly identify, admit and apologise for any mistakes or deficiencies

- set out any remedies

- include information about internal or external review options

- be translated, or copied to an advocate, where the complainant confirms that it will help with their understanding.

The Council officer who dealt with the complaint should provide their contact details, should the complainant have any further questions. Where it is necessary to withhold the Council officer’s identity to protect their safety, use a specific identifying reference to ensure decisions can be traced.

A model template for writing outcomes to investigations is at Appendix D.

Avoiding bureaucratic responses

Councils make decisions under legislation and policies. Template outcome letters that simply refer to the legislative or policy basis for a decision, without a plain English explanation, can appear bureaucratic.

Bureaucratic example:

✖ Your application does not meet the eligibility criteria for a financial hardship plan, pursuant to clause 6(a)(iii) of the Council’s Financial Hardship policy.

✖ Your claim for compensation for damage caused to your vehicle is declined in accordance with section 102(1) of the Road Management Act which provides that a road authority [the Council] is not liable in any proceedings for damages, whether for breach of the statutory duty imposed by section 40 or for negligence, in respect of any alleged failure by the road authority to remove a hazard or to repair a defect or deterioration in a road. This decision is not reviewable.

Plain English example:

✔ Under our Financial Hardship policy, we are unable to accept your application and offer you a payment plan. This is because your income (which includes assets such as your residential and your investment property), is above the threshold set out in the policy.

✔ We have not accepted your claim for compensation. In your claim, you said your car was damaged after driving over a large pothole on Main Street at 2.15am on Tuesday 7 June. The pothole was created as a result of heavy rain after 10pm on Monday 6 June. Our records show that until now, there have been no reports of potholes or similar defects in Main Street.

Under section 102(1) of the Road Management Act, the Council is not liable for the damage to your car, because we were not aware of the pothole hazard at the time the damage occurred. If you have car insurance, you may wish to contact your insurer to make a claim under your insurance policy.

Dealing with 'challenging' vs 'unreasonable' behaviour

The reality is that sometimes complainants to a Council will be frustrated, distressed or simply communicate in ways that some Council staff find confusing or confronting. The Ombudsman defines ‘challenging behaviour’ as any complainant behaviour that your staff find difficult.18 Often the behaviour is not ‘unreasonable’ – that is, the behaviour does not raise health, safety, resource or equity issues – and there are practical steps complaint handlers can take to effectively respond.

The Ombudsman recognises the impact of challenging behaviour. We developed a Good Practice Guide to Dealing with Challenging Behaviour (2018) which sets out a strategy, tools and tips for complaint handlers. The framework below outlines the strategy. Including this framework in your complaint handling process or establishing your own standalone policy, can help minimise the occurrence and impact of challenging behaviour on business and staff wellbeing.

Stage 1 – Prevent

Use good complaint handling techniques. When a complainant sees your processes are fair and reasonable, they are more likely to engage with you and accept outcomes. From the outset, ask the complainant if they have any communication or other assistance needs that your Council can accommodate. 18 Victorian Ombudsman, Good Practice Guide to Dealing with Challenging Behaviour (2018).

Be aware of your own expectations and avoid making assumptions about the motivations behind someone’s behaviour. The way a person communicates can be influenced by a range of factors, including some mental illnesses, disability, cultural background, previous experiences, and personal circumstances. What you perceive from a person’s tone, words or gestures may not be the same as what was intended. Adapt your communication style so your conversation is productive.

Stage 2 – Respond

If someone is very emotional about their complaint, you need to deal with that before you can talk about the issues:

- Take control of your own emotions and the situation, and stay professional.

- Acknowledge how the person feels and give them a chance to talk about how they feel.

- Refocus the discussion on their complaint, once their emotions have settled.

Stage 3 – Manage

Where you consider a person’s behaviour is ‘unreasonable’, you can take steps and implement strategies to manage it. The strategy you use will depend on the behaviour. It may involve ‘calling out’ the behaviour, asking them to ‘stop’, and explaining the consequences if their unreasonable behaviour continues.

Stage 4 - Limit: a last resort

There may be times when nothing you try works and your Council needs to limit a person’s access to your services to protect staff wellbeing and resources. Any limits to a person’s access to your complaints process, or services, must be:

- the least restrictive possible and, in all cases, provide an avenue through which the person can continue to raise concerns

- proportionate to the risk posed by the behaviour

- compliant with your Council’s obligations under anti-discrimination legislation and the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic)

- made or endorsed at a senior level (eg a manager)

- reviewed frequently, depending on the nature of the behaviour and the limitations.19

You must also inform the person about these limits, and give them an option to request a review of your decision.

When does behaviour become ‘unreasonable’?

‘Unreasonable’ conduct is behaviour which, because of its nature or frequency, raises substantial health, safety, resource or equity issues for complaint handlers.20 It can include:

- persistent, unrelenting and incessant attempts to raise issues that have been comprehensively dealt with

- making demands for unattainable or constantly changing outcomes

- a continual unwillingness to cooperate

- constant and repeated arguments that are not based on reason

- acts of aggression, threats, verbal abuse, derogatory, racist or defamatory remarks.

Managing ‘unreasonable’ conduct requires direct intervention (recommended at stages 3 and 4 in the framework) because of the negative impact it has on resources, staff wellbeing and the broader community.

The Ombudsman’s Good Practice Guide to Dealing with Challenging Behaviour (2018) and the New South Wales Ombudsman’s Managing unreasonable conduct by a complainant: A manual for frontline staff, supervisors and senior managers (2021) include strategies for reducing the impact of unreasonable conduct while preserving access to services.

2.8 Confidentiality and privacy

Councils receive personal information about individuals and businesses in the course of carrying out their functions. Councils have an obligation to responsibly collect, handle and protect personal information under privacy and information laws. They must also tell individuals about why they are collecting their information and how it will be handled and used.21

Personal information gathered from a complainant during complaint handling must only be:

- used to deal with the complaint or for a reasonable secondary purpose, such as monitoring complaint trends

- disclosed in a de-identified format where data is publicly released. Data may only be released publicly if it cannot be re-attributed to a person.

- accessed by Council staff where necessary to deal with the complaint, or for a related secondary purpose (eg to identify systemic trends). Ensuring that personal information is stored securely helps prevent unauthorised access, modification or disclosure of the information. Establishing information governance ensures your Council meets its obligations to protect privacy while also allowing it to analyse and use information to improve Council services.

2.9 Providing internal and external review options

Under the 2020 Act, Councils must include in their complaints policy a process for dealing with internal reviews.22 An internal review looks at whether a complaint was managed appropriately, and whether the decisions were sound. Internal reviews should be undertaken by a senior officer who has not been involved in the original complaint. Internal reviews follow good complaint handling steps, including:

- acknowledging the review request

- explaining the process, including the timelines for conducting the review, what it will and will not look at, and the possible outcomes

- providing the complainant and any other parties with an opportunity to present their case

- providing a written outcome, together with reasons, and detail any remedies

- offering external review options, if parties are dissatisfied with the outcome

'Internal Ombudsman'

The term ‘Ombudsman’ is of Swedish origin and refers to an independent office, which provides a free and impartial means for resolving disputes between the citizen and their government.23

Some Councils appoint an ‘Internal Ombudsman’ to deal with complaints. In most cases, the Internal Ombudsman performs an internal review function for the Council.

Referring to a Council officer as an ‘Internal Ombudsman’ is problematic because they are not, and cannot be, independent of the Council. Essentially, the term ‘Internal Ombudsman’ is an oxymoron. It is also confusing for complainants. The Victorian Ombudsman discourages its use and recommends Councils use terms such as ‘Internal review officer’ instead.

3. Learning and improving

Learning from complaints requires Councils to systematically record complaints and their outcomes. A complaint needs to be recorded in sufficient detail to enable your Council to analyse the data and identify thematic trends and issues.

Publicly reporting on the number of complaints your Council receives, as well as what the Council has done in response, enhances transparency. It shows to the community the Council’s commitment to improving its services.

To be able to learn from complaints, Councils need to be:

3.1 recording complaints systematically

3.2 analysing complaint data

3.3 continuously improving complaints systems

3.4 reporting on complaint data and outcomes.

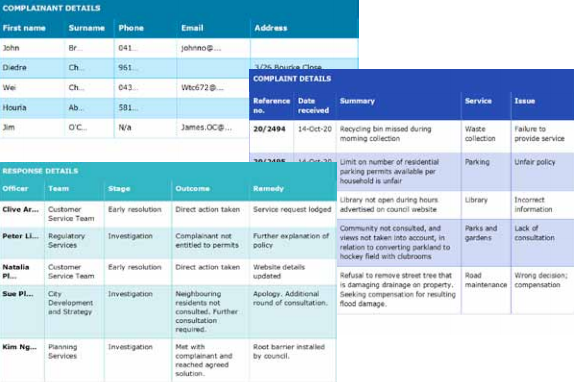

3.1 Recording complaints systematically

All complaints need to be recorded in a systematic way before they can be analysed for trends and issues. Not all Councils have standardised or central systems for recording complaints. Some have different approaches to managing complaints in different areas. But Councils can get good insights from their complaint data by recording the following complaint details:

- The complainant’s name, contact details and communication needs. Demographic data, such as age, disability, language or cultural needs or whether a person identifies as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander can be helpful to improve services to groups. This information can be collected with the complainant’s consent.

- The substance of the complaint according to a list of categories. Complaints can be categorised:

- by service (eg waste collection, property valuation, rates, parking permits, library services)

- by issue (eg failure to provide a service, unreasonable cost, excessive enforcement, delay with communicating or making a decision)

- Who provided the service (eg name of officer, responsible team)

- How the complaint was dealt with (eg through early intervention or investigation)

- The outcomes of the complaint (eg whether the complaint was sustained, the problems identified, and any action taken)

- Remedies

- The name of the officer who determined the outcome of the complaint

- Whether there was an internal review, and its outcome (eg whether the original decision was upheld or overturned).

Simple system for recording complaint data systematically

While some Councils have dedicated complaint management systems, others rely on separate systems that may not be integrated.

To learn from your complaint data, we suggest your Council record basic information consistently, regardless of how the complaint is received, and who manages the complaint. The database fields and examples provided below offer a basic structure:

The data needs to be of sound quality. Train staff on using your complaint management system and recording complaint information consistently; audit data quality; and ensure errors are corrected.

3.2 Analysing complaint data

Sometimes individual complaints can point to a systemic problem; but generally this only becomes clear when looking at complaint data as a whole. Bear in mind:

- the overall number of complaints received can indicate community satisfaction or dissatisfaction

- changes in the number of complaints over time can indicate that satisfaction is improving or dropping

- high numbers of complaints about particular services, issues or teams may suggest systemic concerns that warrant further attention, regardless of whether the complaints are substantiated

- complaints can be driven by a range of factors, other than poor performance, such as:

- changes in community expectations

- increased engagement with the Council and its services (which can be a positive sign)

- inadequate information about a service or barriers to accessing a service or process

- internal review outcomes can be a sound measure of performance and quality of decision-making.

To get the most out of your data:

- spend time thinking about the purpose of your analysis

- plan what are you trying to find out

- what measures you will look at

- how you will validate your analysis.

Regular reporting on complaint data to Council committees or senior leaders can help direct your approach to data analysis. They can provide a useful forum for discussing complaint trends and further action.

3.3 Continuously improving complaints systems

Complaint data analysis provides an empirical basis for improving services, preventing future complaints and driving a continuous improvement mindset.

Conducting a ‘health-check’ of your complaint system is a good way to check you are handling complaints effectively.

The self-assessment tool at Appendix C can be used to check how well your Council’s complaint system is operating against good practice criteria.

3.4 Reporting complaint data and outcomes

Sometimes the public, media and others cast public information about complaints in a negative light. However, demonstrating transparency around your Council’s operations is valuable.

Performance indicators are a good way to measure and monitor your Council’s performance. They also demonstrate your commitment to improving your complaint handling practices and Council’s services.

Useful performance indicators include:

- complaint numbers, categories and outcomes

- timeframes

- service changes or remedies resulting from complaints

- internal review outcomes (eg upheld, partially upheld or overturned)

- the number of complaints escalated to external review.24

Publishing this data, and including it in your Council’s annual report, shows accountability and benefits the community. It also enables Councils to compare their performance and learn from each other.

Appendix A

Australian and New Zealand standards

- Standards Australia, Guidelines for complaint management in organizations (AS/NZS 10002:2014), Standards Australia Limited, Sydney, 2014

- International Organization for Standardization, Quality management – Customer satisfaction – Guidelines for complaints handling in organizations (ISO 10002:2018), Standards Australia Limited, Sydney, 2018

Complaint handling guides

- Commonwealth Ombudsman, Better practice complaint handling guide, 2021

- NSW Ombudsman, Effective complaint handling guidelines, 3rd edition, 2017

- Victorian Ombudsman, Complaints: Good Practice Guide for Public Sector Agencies, 2016

- Victorian Ombudsman, Managing Complaints Involving Human Rights, 2017

- Victorian Ombudsman, Apologies, 2017

- Ombudsperson British Columbia, Complaint handling guide: Setting up Effective Complaint Resolution Systems in Public Organizations, 2020

Dealing with challenging behaviours

- Victorian Ombudsman, Good Practice Guide to Dealing with Challenging Behaviour, 2018

- NSW Ombudsman, Managing unreasonable conduct by a complainant: A manual for frontline staff, supervisors and senior managers, 2021

Appendix B

Model complaints policy for Councils

This model complaints policy is intended as a guide only and is downloadable on this page. Tailor your Council's policy to reflect your organisational capacity and the needs of your community.

The following is intended to help you meet your obligation to have a complaints policy, as required by section 107 of the 2020 Act, and to support your staff to deal with complaints in accordance with the requirements of the Act and good practice promoted in the Ombudsman's Councils and Complaints - A Good Practice Guide (2nd edition)

How to use this document

- Recommended inclusions are in standard type

- Suggested wording is in 'quotation' marks

- Suggestions for drafting the policy and additional guidance are in

[bold and in square brackets]

Complaints policy

| Name of council | |

| Title and version number | [Review complaint handling system every four years, including procedures and key performance indicators] |

| Record number | |

| Effective date | |

| Responsible officer | |

| Date of approval | |

| Review date | [Review your complaint handling system every four years, including procedures and performance indicators] |

| Relevant legislation | Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) Public Interest Disclosures Act 2012 (Vic) |

| Related policies and procedures | [Insert all related policies & procedures with dates eg:

|

[List compliance obligations in relation to specific legislation eg:

|

Scope

Dealing with complaints is a core part of Council business. We value complaints and encourage people to contact us when they have a problem with our services, actions, decisions, and policies. We are committed to:

- enabling members of the public to make complaints about the Council

- responding to complaints by taking action to resolve complaints as quickly as possible

- learning from complaints to improve our services.

We treat every complaint we receive on its individual merits, through clear and consistent processes.

Our complaints policy applies to all complaints from members of the public about Council staff, Council contractors and decisions made at Council meetings. This policy does not apply to complaints about individual Councillors.

What is a ‘complaint’?

A complaint includes a communication (verbal or written) to the Council which expresses dissatisfaction about:

- the quality of an action, decision or service provided by Council staff or a Council contractor

- a delay by Council staff or a Council contractor in taking an action, making a decision or delivering a service

- a policy or decision made by the Council, Council staff or a Council contractor.

In this policy:

‘Council staff’ is any person employed by the Council to carry out the functions of the Council, and the Council’s CEO.

‘Council contractor’ is any third-party engaged by the Council to carry out functions on the Council’s behalf.

‘the Council’ means the body of elected Councillors.

[In this section, you could include:

- any other key terms your Council uses, including those closely related to ‘complaint’, such as a ‘request for service’, ‘feedback’ or ‘staff grievance’.

- communications that your Council considers are outside the definition of ‘complaint’. These exclusions must remain consistent with the definition of ‘complaint’ in the 2020 Act.]

How to make a complaint

Any member of the public can make a complaint.

Complaints can be made by:

Telephone: [Insert telephone number]

Online:

[Insert web address. If you have an online complaint form, include instructions on how to access it from the home page, eg From www.Councilwebsite.vic.gov.au. Click on ‘Contact us’, then go to ‘Make a complaint’]

Email:

[Insert email address]

Post:

[Insert name of Council and postal address]

In person:

[Insert location/s]

[In this section, include additional information that will help to resolve a complaint:

- Advising a complainant to try and raise their concerns directly with the Council staff member. If the complaint is not resolved, the complaint can be escalated to a more senior officer.

- Listing what information is helpful for a complainant to provide to the Council:

- ‘name and contact details. You can complain anonymously, but this may limit how the Council responds to you

- identify the action, decision, service or policy you are complaining about, and why you are dissatisfied

- give us relevant details, such as dates, times, location or reference numbers, and documents that support your complaint

- the outcome you are seeking from making your complaint

- whether you have any communication needs.’]

We are committed to ensuring our complaints process is accessible to everyone. Tell us if you have specific communication needs or barriers, and we can assist you by:

- using an assistance service, such an interpreter or TTY (for free)

- talking with you if you have trouble reading or writing

- communicating with another person acting on your behalf if you cannot make the complaint yourself.

Our complaints process

When you complain to us, we will record and acknowledge your complaint within five business days. We will initially assess your complaint to decide how we will handle it. This may happen while we are talking with you.

After our initial assessment, we may:

- take direct action to resolve your complaint

- refer your complaint to the relevant team or manager for investigation

- decline to deal with your complaint if you have a right to a statutory review of your complaint (such as a right of appeal to VCAT).

Where possible, we will attempt to resolve your complaint at the time you first contact us. If we decide not to take action on your complaint, we will explain why, and, where possible, inform you about other options.

[In this section, you can include details of your tiered approach to complaint handling, what firstcontact resolution looks like, and what might not be amenable to first-contact resolution. Eg:

- ‘Early resolution of a complaint may involve arranging for the Council to give you advice or explaining why we are not going to take action on your complaint.

- It may not be possible to resolve your complaint when you first contact us if your complaint requires deeper consideration or investigation by a particular team or officer, or needs to follow a statutory process or cannot be resolved satisfactorily.’

You can also include in this section information about specific processes in place for dealing with complaints about the CEO or Council contractors, including who is responsible for considering and responding to these complaints.]

If we cannot resolve your complaint quickly, we will refer it to the relevant team or manager to investigate. We will tell you who you can contact about the investigation.

We aim to complete investigations within 30 calendar days, and will tell you if the investigation will take longer. We will update you every 30 calendar days about progress until the investigation is completed. We will inform you of the outcome of your complaint and explain our reasons.

[In this section, include details about your investigation process:

- ‘As part of our investigation we will:

- assess the information against relevant legislation, policies and procedures

- refer to Council documents and records

- meet affected parties to consider possible solutions

- advise you in writing of the outcome and our reasons ...

If your Council does not have a standalone policy on dealing with ‘behaviour which Council staff find challenging or unreasonable’, you can also include in this section:

- We require our staff to be respectful and responsive in all of their communications with members of the public. We expect the same of you when you communicate with our staff.

- We may change the way we communicate with you if your behaviour or conduct raises health, safety, resource or equity issues for Council staff involved in the complaints process.’]

How to request an internal review

If you are dissatisfied with our decision and how we responded to your complaint, you can request an internal review.

The internal review will be conducted by a senior Council officer who has not had any prior involvement with your complaint.

We will inform you of the outcome of the internal review and explain our reasons within 30 calendar days of the date of this letter.

How to request an external review

There are external bodies that can deal with different types of complaints about us.

You can request an external review from the following organisations.

| Complaint | Organisation to contact for external review |

| Actions or decisions of a Council, Council staff and contractors. This includes failure to consider human rights or failure to act compatibly with a human right under the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) | Victorian Ombudsman www.ombudsman.vic.gov.au |

| Breaches of the Local Government Act | Local Government Inspectorate www.lgi.vic.gov.au |

| Breach of privacy. Complaint about a freedom of information application | Office of the Victorian Information Commission www.ovic.vic.gov.au |

| Corruption or public interest disclosure (‘whistleblower’) complaints | Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission www.ibac.vic.gov.au |

| Discrimination | Victorian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission www.humanrights.vic.gov.au |

| Council elections | Victorian Electoral Commission www.vec.vic.gov.au |

How we learn from complaints

Complaints from people who use or who are affected by our services provide us with valuable feedback about how we are performing.

We regularly analyse our complaint data to identify trends and potential issues that deserve further attention. We use this information to come up with solutions about how we can improve our services.

We are open and transparent about the complaints we have received, and what we have done to resolve them. We publish our complaint data including in our annual report.

Your privacy

We keep your personal information secure. We use your information to respond to your complaint, and may also analyse the information you have provided for the purpose of improving services that relate to your complaint.

Where we publish complaint data, personal information is removed.

[In this section, also include specific details about how you record or use complaint data. Eg ‘When you complain to us we ask you to provide and will record:

- your name and contact details

- whether you have any communication or assistance needs that can be reasonably accommodated

- demographic information to help us understand the needs of our community (if you consent to giving us this information)

- what you are complaining about

- what outcome you are seeking.’]

Responsibilities

All Council staff, Councillors and Council contractors are responsible for contributing to our complaints process.

| Role | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Chief Executive Officer |

|

| Senior leaders and managers |

|

| All Council staff |

|

| Councillors |

|

| Contractors |

|

Appendix C

Self-assessment tool for Councils

This tool can be used to assess whether your Council is implementing good practices to enable, respond to and learn from complaints. The targets in this Guide reflect the three concepts which are fundamental to complaint handling. The focus areas represent the core elements of a good practice complaint process as set out in the Victorian Ombudsman's Councils and Complaints - A Good Practice Guide (2nd edition).

This tool is downloadable as a word document from this page.

Appendix D

Model wording for written outcomes to investigations

[Date]

[Address/Email]

Dear...

Thank you for your complaint which I received on 23 February 2020, and for discussing your concerns with me.

As you are aware, I have investigated your complaint about …

[Refer to the issues identified by the complainant, and what they believed went wrong. For example, ‘our decision not to waive your waste collection charge’.]

My investigation involved …

[Describe what steps were taken as part of the investigation. For example, ‘considering the Council’s policies, reviewing our service arrangements and the outcome you are wanting, bearing in mind the broader impact on our service and the community as a whole.’]

As a result of my investigation, I have decided that …

[Explain what your conclusions are, and support them with reasons and evidence. If the Council is taking remedial action, explain what it is and how it addressed the issue. For example, ‘I have found that we did not consider your personal circumstances, and we should have given you extra time to pay the registration fee for your cats when you requested a payment extension before the due date.

We have reminded staff to be more flexible in answering similar requests in the future, and we have updated our policies to support this approach. Nonetheless, I am sorry you did not have a positive experience in this instance, and hope that the changes we have made give you some confidence that we are trying to improve our services.’]

If you are dissatisfied with the outcome of your complaint, you can request an internal review of the handling of your complaint by …

[Explain what the complainant needs to do to request an internal review. For example, ‘writing to review@CouncilEmail, and outlining how you believe the decision was wrong’.]

You may also have an option to seek a review of your complaint by contacting …

[Explain how a person can request an internal review. If you are providing an outcome to an internal review, include information about external review options available, including details of the relevant oversight/review body. For example ‘... the Victorian Ombudsman, which can deal with complaints about actions and decisions of Councils and other Victorian public bodies’.]

If you would like to discuss your complaint further, you are welcome to contact me by calling … or emailing ….

Yours sincerely

[Name of responsible officer and title]

…

This letter template is downloadable as a word document from this page.

Template downloads

- Download Appendix B - Model complaints policy for CouncilsDOCX - 27.9KB

- Download Appendix C - Self assessment tool for CouncilsDOCX - 28.5KB

- Download Appendix D - Complaint investigation outcome letter templateDOCX - 22.4KB

- Victorian Ombudsman, Councils and complaints - A report on current practices and issues (2015).

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) Part V Division 1.

- Standards Australia, Guidelines for complaint management in organizations (AS/NZS 10002:2014) (2014).

- International Organization for Standardization, Quality management – Customer satisfaction – Guidelines for complaints handling in organizations (ISO 10002:2018) (2018).

- Standards Australia, above n 3.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) ss 141, 143.

- Section 107(4) of the Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) requires this to be done within 6 months of 1 July 2021.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) s 107(1)(c).

- As established by the CEO under section 46(3)(c) of the Local Government Act 2020 (Vic).

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) s 123(3)(c).

- Publishing your Council’s complaints policy, and information about the complaints process, aligns with the transparency principles set out under section 58 of the Local Government Act 2020 (Vic).

- Victoria’s anti-discrimination laws are set out in the Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic) and the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic). The Commonwealth’s anti-discrimination laws are set out in the Age Discrimination Act 2004 (Cth), Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth), Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) and Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth).

- Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic).

- Web Accessibility Initiative, Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) (11 December 2008) <https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG20/>.

- Organisations, including Councils, must afford reasonable adjustments to people with a disability under the Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic) and Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth).

- See Tania Sourdin, Jamie Carlson, Martin Watts and Christine Armstrong, Return on Investment of Effective Complaints Management (SOCAP and University of Newcastle, 2018).

- Tania Sourdin, Consumer Experience on Complaints Handling and Dispute Resolution – A Research Study Undertaken in Victoria, Australia (La Trobe University, 2007).

- Victorian Ombudsman, Good Practice Guide to Dealing with Challenging Behaviour (2018).

- Also see Slattery v Manningham City Council [2013] VCAT 1869 (30 October 2013) (Senior Member Nihill).

- New South Wales Ombudsman, Managing unreasonable conduct by a complainant - A manual for frontline staff, supervisors and senior managers (2021).

- Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic) and Health Records Act 2001 (Vic). Also see the Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner’s information for Councils at ovic.vic.gov.au/privacy/local-government-and-privacy.

- Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) ss 107(1)(e) and 107(2).

- The Australian and New Zealand Ombudsman Association (ANZOA) promotes the correct use of the term ‘Ombudsman’ and campaigns for stronger controls for the use of the term, refer to <www.anzoa.com.au/about-ombudsmen.html>.

- The Ombudsman publishes information about complaints received about each Victorian Council in our annual report <www.ombudsman.vic.gov.au/about-us/annual-reports-and-policies/annual-reports>. We can be contacted for more information.