Misconduct in public organisations: A casebook

Date posted:Foreword

My office deals with hundreds of allegations of misconduct every year. Many are not substantiated; but others are, yet for various reasons, including the welfare of the people involved, these stories are not made public. This report, with its deidentified case studies, lifts the veil on this important segment of Ombudsman work.

Its themes are, sadly, not new. Conflicts of interest, favouritism, and misuse of public funds continue to feature as they have in previous Ombudsman reports. But the stories are different, and each holds valuable lessons from which others can learn.

Sometimes people do the wrong thing and go to some lengths to conceal it – such as the Manager who took over 40 days of paid leave without putting in a leave request, even pretending they had attended an off-site meeting. Or the Executive who not only failed to fully disclose their misconduct record but had a history of making only partial disclosures in other roles.

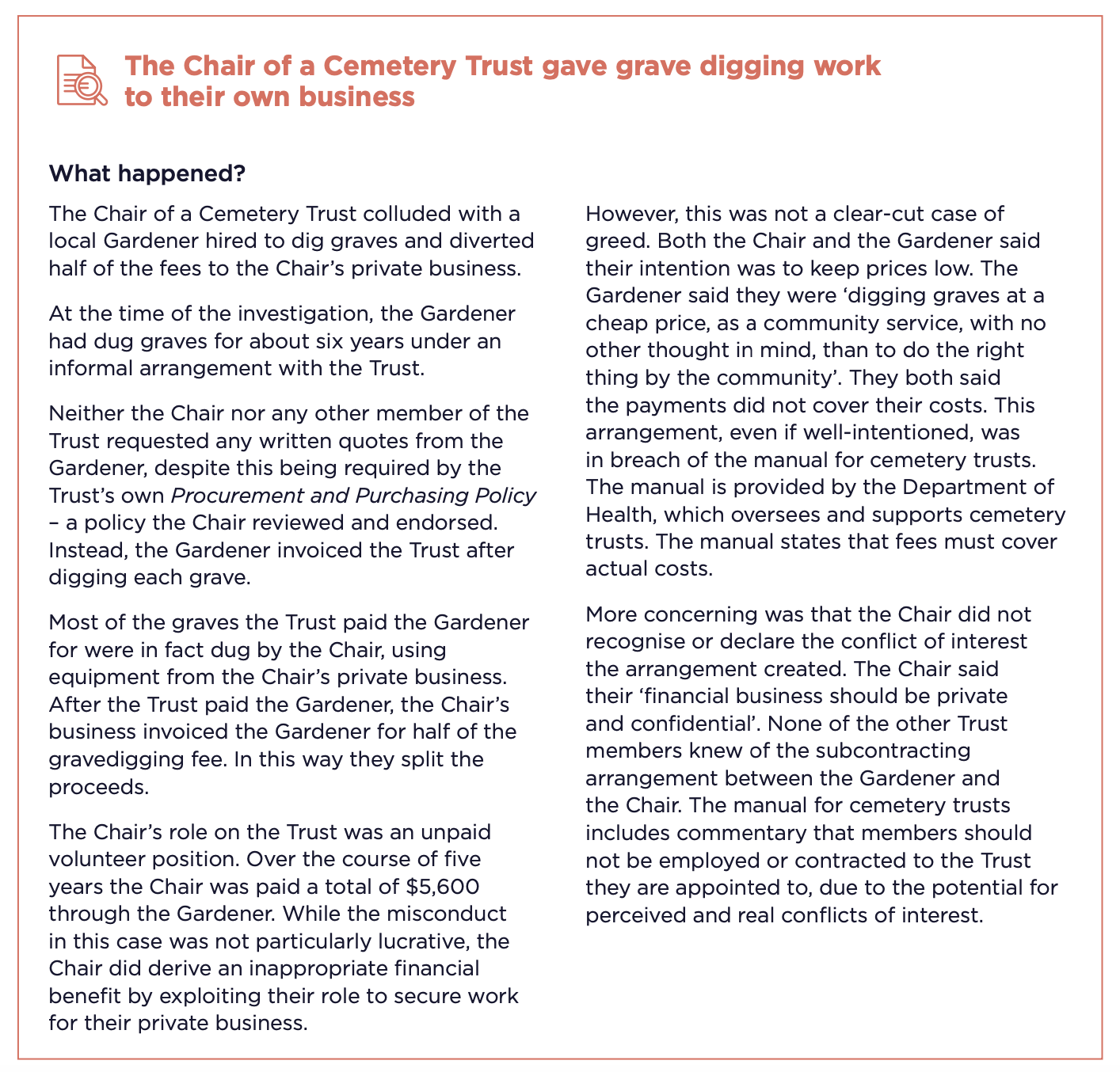

In other cases, people simply do not recognise they are doing the wrong thing. It is still a common finding of our investigations that conflicts of interest are poorly understood by many people in public roles. The Chair of a Cemetery Trust whose business also dug the graves; the Manager who employed their friend without following due process. Here the motives are less devious: the graves might have been dug at the cheapest rate; the friend may have been the best person for the job.

But due process – like declaring and managing conflicts of interest – exists for good reasons. Good processes protect both parties from the perception of favouritism. In recruitment, a lack of transparency can make recruiters appear dishonest and candidates undeserving, even if they are the best person for the job. Not following due process undermines trust.

Public funds may be misused because people opportunistically take advantage of an organisation’s poor financial controls; or because the organisation’s culture allows poor conduct to continue unchecked. The cases exposing these failings also underline the importance of leaders modelling strong public sector values and building a culture in which staff feel able to challenge bad behaviour.

Public trust – striving to earn and sustain it – is a vital challenge for the public sector. Tens of thousands of public sector workers do the right thing, often heroically and without fanfare, every day. They are the ones who suffer most when people in public roles fail to uphold that trust. For their sake, and for the reputation of the public sector, these lessons must be learnt.

Deborah Glass

Ombudsman

Background

Almost 355,000 people are employed in the Victorian State public sector – around 10 per cent of the entire Victorian workforce. More than 31,000 others are members of Victorian public sector boards. These people include health, education, transport, corrections, emergency and land management workers. Some of them are unpaid volunteers, for example those on small committees managing local community halls. At the other extreme are executives with substantial salaries, or board members leading organisations responsible for billions of public dollars annually.

While these people engage in a wide range of jobs in varied circumstances, there is a consistent set of expectations about their behaviour. The Public Administration Act 2004 (Vic) states that State public officials must act in a manner that is consistent with the public sector values of responsiveness, integrity, impartiality, accountability, respect and leadership.

This legislation is supported by the Code of Conduct for Victorian Public Sector Employees (‘VPS Code of Conduct’), the Code of Conduct for Directors of Victorian Public Entities and the Code of Conduct for Victorian Public Sector Employees of Special Bodies, which explain how State public officials should demonstrate these values.

The 79 councils in local government in Victoria also employ tens of thousands of staff and have hundreds of elected councillors. The local government sector is not covered by the Public Administration Act, but has its own conduct frameworks based on the Local Government Act 2020 (Vic).

Some people working in public roles, including some private contractors engaged by public organisations, may be subject to the same, or other conduct requirements set out in sector-specific legislation and codes of conduct, such as Victoria’s Code of conduct for disability service workers or the Victorian Teaching Profession’s Code of Conduct.

Most people in public roles in Victoria are also required to conduct themselves in a way that is compatible with the 20 fundamental human rights set out in the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic). This Act applies to ‘public authorities’, including Victorian State and local government and many private organisations delivering services on their behalf.

The State public sector, the local government sector and in some cases, their contractors or the bodies they provide funding to, are also subject to the Public Interest Disclosures Act 2012 (Vic). This Act defines various types of ‘improper conduct’ by public officers. It sets up a framework for reporting and investigating ‘improper conduct’ and providing protection for whistleblowers.

The conduct and integrity requirements in these various pieces of legislation, codes and guidance documents sometimes overlap, and the pathways for dealing with poor conduct can differ depending on the organisation, the circumstances and the gravity of the conduct. However, the objectives and values underpinning these frameworks are the same.

They set high standards of behaviour and accountability for anyone exercising public powers, carrying out public functions, controlling public resources or being paid with public money. They acknowledge that people working in public roles occupy a position of trust within the community and create consequences for those who breach that trust.

While each of the investigation case studies in this report is taken from the Victorian ‘public sector’ (as defined in the Public Administration Act), the lessons drawn from them can be applied to most public organisations. This includes local councils and a range of private bodies exercising public functions or receiving public funding. Throughout this report, we use the term ‘public organisations’ to refer to this broader category of organisations.

The case studies contain familiar issues. Almost 10 years ago, in 2013, the previous Ombudsman published a Report on issues in public sector employment which highlighted nepotism, conflicts of interest and inadequate pre-employment screening as key risks.

The Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (‘IBAC’) has reported on similar issues. Its 2018 report on Corruption and misconduct risks associated with employment practices in the Victorian public sector covers nepotism, favouritism and pre-employment screening practices. Its 2019 report, Managing corruption risks associated with conflicts of interest in the Victorian public sector, and its 2020 report, Unauthorised access and disclosure of information held by the Victorian public sector also discuss relevant topics.

These issues still persist. Throughout her term, the current Ombudsman has also publicly reported on a range of investigations involving misconduct. This casebook contains a sample of the sorts of issues we see; it demonstrates a need for continued vigilance. The purpose of this report is to educate and inform public sector organisations and the Victorian community about conduct risks and to share lessons about how these risks can be reduced.

What is misconduct?

In this report, we use the general term ‘misconduct’ to describe behaviour that breaches the conduct standards required of someone in a public role. The case studies included are examples of investigations where the Ombudsman found someone engaging in misconduct, or systems failing to manage misconduct risks.

It is important to note that not all misconduct is equally serious. It can span a broad spectrum of behaviour, from someone in a public role providing poor service to a client or ignoring a reasonable direction from their manager, through to misusing public funds.

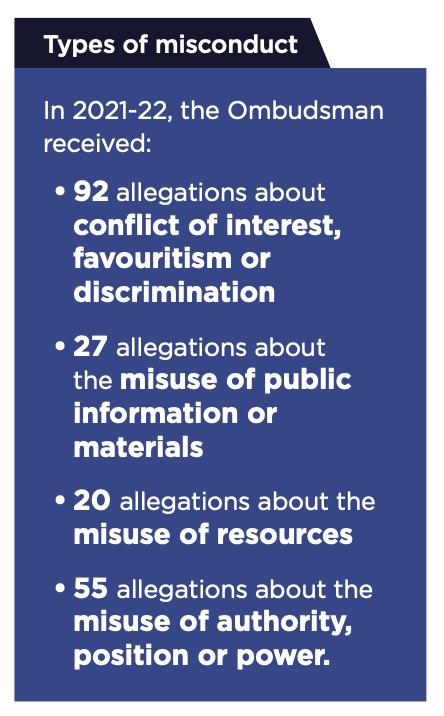

What sort of misconduct is more common?

Although misconduct occurs across a wide range of public organisations providing different services, we see certain types of poor behaviour more frequently.

One of the most frequently complained about issues is undeclared or poorly managed conflicts of interest. This report contains an example of someone contracting work to their own company.

Related to conflicts of interest is people using their position for private gain. Recruitment decisions in the public sector are meant to be fair, transparent and merit-based, but recruitment is an area which has a high risk of misconduct. The Ombudsman regularly receives complaints about jobs being given to ‘mates’ or family members without proper processes being followed. One case study in this report shows a manager recruiting a friend.

We also receive complaints about people withholding relevant information during recruitment. Another of the cases in this report shows a public official failing to disclose their history of misconduct to a new employer.

Another situation where there can be an opportunity for someone to directly benefit is procurement. Procurement cases often show people misusing public funds and resources. An example in this report is someone spending school funds on their private sporting team.

There is also an example showing the misconduct risks created by a lack of transparency in procurement processes in the case of an organisation using an ‘off-book’ bank account and failing to accurately report consulting expenses. In this instance the organisation’s processes did not accord with public sector values and led to allegations of financial impropriety.

The types of conduct discussed in this report can overlap, but they are often tied to a lack of transparency. All public organisations need to open themselves to scrutiny so the public can be assured they are acting in the public interest and money is being wisely spent. Behaviours which fail to do this can erode public trust.

How do public organisations deal with misconduct?

Public organisations are responsible for employing strategies to both prevent and effectively deal with misconduct.

Pre-employment screening and probation

All public organisations should have a documented approach to pre-employment screening.

In the Victorian public sector, pre-employment screening is guided by Victorian Public Sector Commission (‘VPSC’) policy. In 2018, VPSC began to introduce pre-employment misconduct screening policies and guidance for public sector employers and candidates.

These policies mean most people who apply for roles in the Victorian public sector are required to complete a statutory declaration about their conduct history before they are appointed.

VPSC has done significant work to strengthen pre-employment screening processes with the aim of striking an appropriate balance between ensuring efficient recruitment and procedural fairness for applicants. VPSC’s current model statutory declaration requires candidates to declare if:

- their employment with any previous employer was terminated due to misconduct

- they have been found to have engaged in misconduct in their employment in the past seven years (10 years for executive roles)

- they are currently the subject of an investigation relating to their conduct in their employment

- they have ever resigned from employment while the subject of an investigation relating to their conduct in their employment.

This helps employers make an informed decision about whether the person is suitable for the role. Some organisations or positions may have more rigorous screening processes, depending on the nature of the work.

Organisations can also use probation processes to identify and filter out new employees who demonstrate poor conduct in the early stages of employment.

Education

Public organisations are responsible for educating their leaders, staff and volunteers about their responsibilities and the expected standards of behaviour. Training on policies and procedures should highlight how these are underpinned by organisational values with a view to fostering a culture of integrity across the organisation. Targeted training of individuals or groups may also be needed where conduct issues are identified.

There is a wide range of guidance available to help public organisations educate themselves about integrity issues and manage misconduct risks. VPSC, for example, produces codes of conduct and also policies and guidelines to prevent misconduct and guide the behaviour of people in public roles. IBAC provides advice, training and education services to help the public sector prevent corruption. The Ombudsman provides education to people in public roles aimed at improving service standards to the community, including regular training about a critical misconduct risk, conflict of interest.

The Ombudsman, IBAC and the Local Government Inspectorate also produce public reports on investigations involving misconduct, such as this one. These contribute to the ongoing education of Victorian public organisations about misconduct risks.

Investigation and discipline

Of course, no matter how careful organisations are in their hiring practices or how much they work to prevent misconduct, there will always be the potential for people to do the wrong thing. Where misconduct is suspected, an organisation may investigate the allegation internally or outsource that investigation. Investigation processes need to be timely, fair and robust.

If minor misconduct is found, organisations may respond by better training the officers involved in their responsibilities and expected behaviours. More serious misconduct can result in formal disciplinary action against an employee and in the most serious cases, immediate dismissal.

Depending on the type of misconduct suspected, the organisation may also need to refer the allegation to IBAC to determine whether it is a ‘public interest complaint’ and covered by the Public Interest Disclosures Act. Public organisations are also required by the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission Act 2011 (Vic) to notify IBAC when they suspect corrupt conduct has occurred.

What is the Ombudsman’s role in investigating misconduct?

The Ombudsman investigates many matters involving suspected misconduct every year. These matters are usually allegations of ‘improper conduct’ referred to the Ombudsman by IBAC as public interest complaints (or ‘whistleblower’ complaints).

IBAC may also refer these types of complaints to the Local Government Inspectorate to deal with, when the allegations concern conduct within councils. IBAC itself investigates allegations of serious or systemic corruption.

The Ombudsman has broad Royal Commission-like investigation powers in relation to public organisations and can also require private parties, such as contractors and ex-employees, to provide evidence. Internal misconduct investigations carried out by organisations have more limited powers and usually cannot compel someone to provide evidence.

Not all public interest complaints referred to the Ombudsman are investigated. We resolve many by making detailed enquiries, without having to commence a formal investigation. In 2021-22 we finalised 167 public interest complaint allegations through enquiries and 39 through investigations.

In the past three financial years we finalised investigations into 205 public interest complaint allegations and substantiated or partly substantiated 57 of those allegations. While many of these allegations we investigate are not substantiated, we often find poor organisational processes or officers breaching conduct requirements. This behaviour may not amount to ‘improper conduct’ for the purposes of a public interest complaint but still needs to be addressed. In these cases, the Ombudsman makes findings and recommendations to reduce misconduct risks, such as improved processes or targeted integrity training for individuals or teams. We may also recommend that organisations take disciplinary action against officers who have breached behavioural requirements.

The Ombudsman is required to report misconduct during or after an investigation to the heads of the relevant organisations.

Our investigations, by the numbers

The investigations discussed in this report involved:

Case studies

This report details cases the Ombudsman investigated in which allegations of misconduct were substantiated or where systems intended to manage misconduct risks failed.

Misconduct can be a failing to meet any of the public sector values, and it is essentially related to integrity. The VPS Code of Conduct specifies that State public officials should demonstrate integrity by:

- being honest, open and transparent in their dealings

- avoiding any real or apparent conflicts of interest

- using their powers responsibly

- reporting improper conduct

- striving to earn and sustain a high level of public trust.

The cases discussed in this report show public organisations and people in public roles failing to comply with procurement, recruitment and financial reporting requirements as well as the terms of their own employment contracts and the VPS Code of Conduct.

Some of the cases occurred a number of years ago. Since then, many of the organisations involved have improved their systems and practices both in response to our investigations and of their own initiative. While we continue to see positive developments in education and policy across the sector, there are still further improvements that can be made and lessons that can be taken from these examples.

Being honest, open and transparent

All the case studies in this report show people in public roles failing to be honest, open or transparent in their dealings. The starkest examples of staff hiding the truth are the case of a Manager who failed to attend work without applying for leave and the case of an Executive who did not disclose their history of misconduct to a new employer.

Avoiding conflicts of interest

As well as failing to be transparent in their dealings, these cases show staff failing to declare and manage conflicts of interest. In both cases, one about the Chair of a Cemetery Trust subcontracting work to themselves and the other about a Manager recruiting a friend, the officers did not recognise their situations as conflicted. This reflects a common finding of our investigations – that conflicts of interest are poorly understood by many people in public roles.

Using powers responsibly

As well as showing a failure to be honest and transparent, this case illustrates a public employee misusing their powers and misappropriating school funds for personal benefit.

Reporting improper conduct

These two cases show a lack of transparency and misuse of public money – but also show environments where people were aware of these practices and failed to report them. Both cases, one about an organisation misspending money on gifts and alcohol and the other about an organisation obscuring its financial practices, demonstrate the important role organisational culture plays in preventing misconduct. While individual misconduct was not substantiated in either example, they both show systems and practices which left organisations vulnerable to misconduct.

Conclusions

This report details just seven examples of misconduct we have investigated over recent years, but we receive hundreds of allegations of concerning conduct each year.

The report highlights practical ways organisations can reduce opportunities for misconduct to occur. The simplest of these is ensuring they have clear and up-to-date policies that accord with relevant legislation, particularly in the problem areas of recruitment and procurement.

The organisation that misused public money on gifts, alcohol, fines and funeral expenses lacked clear policies in some of these areas, meaning staff could not know what was and was not permitted.

In addition to having sound policies, organisations need to educate their staff about them. Of course, there will sometimes be people who fail to follow policies or try to circumvent them. The cemetery where the Chair subcontracted work to themselves had policies about requiring written contracts and about fees having to cover costs, but these were not followed.

The Manager who recruited a friend tried at first to fill the position without advertising it. When advised this wasn’t permitted by the policy, the Manager ‘complied’ with the policy by advertising the position for the shortest time possible, over a long weekend.

This behaviour of ‘complying’ with a policy just enough for misconduct to go undetected was also seen in the case of the Executive who failed to disclose their history of misconduct. They were required to complete a Declaration of Private Interests form, so they completed it – but without fully answering the questions.

In this case, the Department also failed to follow policy. They should have required the Executive to provide a statutory declaration about their history before hiring them. This process is designed to address the ‘recycling’ of employees with histories of questionable conduct through public sector roles.

Even where VPSC screening processes are followed, there is still a risk of applicants dishonestly hiding their misconduct history without immediate consequences. The current guidance ‘strongly recommends’ that information provided in statutory declarations be verified for high-risk roles, but does not require it.

A process that requires all misconduct declarations for certain types of roles (such as Executive positions) to be verified, irrespective of whether an adverse declaration is made, could significantly reduce the opportunity for people to take advantage of the system.

Of course, having a sound policy is not enough. Compliance with policies needs to be actively monitored and where necessary, enforced. This can become increasingly difficult at senior levels within an organisation. The Department did not challenge the inadequate answers provided by the Executive who failed to disclose their misconduct history on the Declaration of Private Interests form.

Staff can be reluctant to challenge people in senior positions. All public organisations need to create a culture of integrity where staff feel comfortable questioning their superiors when they see them failing to comply with policy. Staff need to know they will be protected if they speak up and that issues will be appropriately investigated.

Where organisations are small, like a school, or made up of volunteers, like a Cemetery Trust, fostering integrity can sometimes be more difficult. Staff and volunteers at small public organisations are held to similar standards as employees of departments. However, they are unlikely to have had much training or practical experience to help them understand conflicts of interest. Often these organisations operate within smaller communities, where conflicts of interest are more likely to occur. Lead agencies, such as departments, need to take a leading role in educating people at the smaller organisations they oversee about integrity issues and the expectations of departmental policies.

In addition to policies, organisations need to have effective internal controls over public funds and resources. The employee who spent school funds on their sporting team was only able to misuse public resources because there were insufficient controls over the school’s invoicing process.

Financial control systems need to be fit for purpose and reviewed as circumstances change. The case of the Manager who was paid for hours they did not work demonstrates this need to adopt more contemporary methods of oversight. The traditional approach to monitoring leave failed, as it relied on the Senior Manager having visibility of the Manager’s work attendance. As remote and flexible working arrangements become more common, the risk of employees misusing leave entitlements increases. Policies need to keep pace with changes in how people work.

To reduce misconduct, it is also important to understand why people engage in this type of behaviour. For some, it appears opportunistic – a employee who processes invoices without sufficient oversight sees that it would be easy to have the school pay for their private expenses.

Other cases show misconduct arising from people’s difficult personal circumstances. The Manager who was paid for hours they did not work was struggling with a complicated personal situation and cited this as the cause of their behaviour. This is not uncommon for the subjects of misconduct investigations.

Organisations need to be mindful of how they can support their employees when their personal difficulties impact them at work. The Senior Manager did try to help, suggesting the Manager access the Department’s Employee Assistance Program. In this case, the intervention was not enough, but it does provide a positive example of management actively trying to support their staff.

It is also critical that the welfare of staff being investigated for misconduct is carefully considered by organisations. Welfare supports are especially important if the employee’s struggles with a difficult personal situation contributed to their behaviour. Misconduct investigations are stressful not only for the people being investigated, but also for any of their colleagues who become involved. Organisations must plan for and follow through with appropriate welfare support during misconduct processes.

While some cases showed examples of positive management behaviour, unfortunately we also saw failures in accountability. At the organisation that used an ‘off-book’ account that hid payments from scrutiny, many management staff knew about the improper practice but the risk was not eliminated.

All public sector employees are expected to act with integrity, but this expectation is even higher for executives. When it comes to misconduct, the role of an organisation’s leadership team is not only to ensure staff compliance with policies but also to model integrity.

The cases in this report are grouped under four of the characteristics of integrity identified in the VPS Code of Conduct. But the Code contains a fifth – striving to earn and sustain a high level of public trust. All of the cases in this report show people in public roles failing to do this. By its nature, misconduct undermines public trust in publicly funded organisations. There will always be the potential for people to do the wrong thing, but this report provides organisations with practical ways to reduce misconduct and maintain or rebuild public trust.

Appendix 1: Procedural fairness

This report contains adverse comments about:

- a Manager at a government Department

- an Executive at a government Department

- a Chair of a Cemetery Trust

- a Manager at a government organisation

- an employee at a school.

These adverse comments were first made in the original investigation reports upon which the case studies in this report are based. Each individual and organisation was provided with the opportunity to respond to the substance of those comments before the original reports were finalised.

In accordance with section 25A(3) of the Ombudsman Act 1973, any other persons who are or may be identifiable from the information in this report are not the subject of any adverse comment or opinion. They are identified in the report as the Ombudsman is satisfied that:

- it is necessary or desirable to do so in the public interest

- identifying those persons will not cause unreasonable damage to those persons’ reputation, safety or wellbeing.