WorkSafe 3: Investigation into Victorian self-insurers’ claims management and WorkSafe oversight

Date posted:Foreword

They helped me transition to a new position and get the treatment I needed.

Comment from injured worker

They took months to start my payment and have made many mistakes with my weekly payments causing a huge amount of stress in an already stressful period.

Comment from injured worker

This is my third report into Victoria’s workers compensation scheme. It concerns an area I did not look at in my two previous reports; what happens when companies are authorised by WorkSafe to handle their own claims, rather than using a WorkSafe-appointed agent.

My previous reports were highly critical of agent practices and WorkSafe’s oversight of them, and have resulted in significant reforms, which I welcome. But many people expressed concerns that those reforms did not extend to companies acting as self-insurers. Did the same problems exist? Is it appropriate for those reforms to be extended? This investigation seeks to answer those questions.

There is an obvious power imbalance between injured workers and their employer, which can be exacerbated where the employer is also their insurer. On the other hand, when an employer offers tailored rehabilitative support, this relationship can also be an advantage.

Thirty-four companies – covering about 120,000 Victorian workers and including many of Victoria’s largest employers – are currently approved to manage their own claims. The number and scale of companies acting as self-insurers imposed some challenges on the investigation; it was simply not practicable to fully explore the decision-making practices of each. We therefore focused on complaints, but acknowledge that self-insurers manage many claims and most are handled without complaint.

We found some self-insurers performing well and delivering the benefits the system intends. But the cases we examined in detail exposed large differences in both practice and capability. It was apparent that self-insurers’ claims management processes did not always produce fair outcomes for workers, and that some echoed the undesirable practices used by WorkSafe agents that my two previous reports exposed.

Given the wide variance of practices across 34 companies, we focused on the role of WorkSafe, which is responsible for approving and monitoring self-insurers to enforce performance standards and promote good decision-making.

Ultimately, we found that more needs to be done – by WorkSafe, to ensure its oversight role is meaningful, and by government, to ensure greater consistency for workers.

We found multiple lost opportunities in WorkSafe’s oversight, including a reluctance to become involved when self-insurers make unsustainable decisions and to use its approval power to support compliance.

WorkSafe has fewer levers for dealing with self-insurers than for agents. In particular, it has no power to direct a self-insurer to overturn a decision. However, WorkSafe seemed unwilling to use the levers it has. We were troubled by WorkSafe’s tendency to use its discretion to approve the maximum six-year term for self-insurers with claims management performance issues. There is also little transparency regarding self-insurers, with WorkSafe publishing little information about their performance.

The picture we saw was not of a broken system, but a patchy and unequal one. Workers should not have a fundamentally different claims experience depending on who their employer is. All self-insurers are equally bound by legislation to ensure that compensation ‘is paid to injured workers in the most socially and economically appropriate manner, as expeditiously as possible’.

I am pleased that WorkSafe acknowledges it needs to do more and is committing to greater vigilance in its regulatory oversight. Reviews and assessment should be purposeful and result in timely regulatory action; ensuring fair outcomes are achieved and decisions are made that are compatible with human rights.

I said in my first WorkSafe report, in 2016, that workers compensation has a fraught history; successive governments have wrestled with the complexity of creating a scheme that is both financially viable and fair. I acknowledge that the government continues to do so. The modest reforms proposed here should increase fairness – for example, by giving WorkSafe the power to direct self-insurers – without affecting financial viability.

The government and WorkSafe have responded admirably to my previous recommendations to ensure a fairer, more equitable system – for the sake of the next generation of injured workers and the community that bears the cost. It is in everyone’s interests to promote sustainable and timely decision-making on what are not merely numbers, files or claims, but people’s lives and livelihoods.

Until all workers in Victoria with the right to claim compensation have the same rights when they disagree with a decision, the system will not be truly fair.

We will continue to monitor both the successes and gaps in the system through the complaints made to us, and this report exposes the gaps around self-insurers. It has been a long journey to systemic fairness, and we are not there yet.

Deborah Glass

Glossary

| Arbitration | A process in which a binding decision is made in relation to a dispute. Arbitration is sought when a dispute has not been settled at conciliation. |

| Case Manager | Primary contact for both the employee and employer. The Case Manager's primary role is to manage a portfolio of claims by coordinating the treatment and recovery of injured workers. |

| Claimant | An injured worker who makes a workers compensation claim. |

| Conciliation | A dispute resolution process that brings the people involved in a disputed claim together to try to achieve an agreement. The people involved include the injured worker, the self-insurer and/or their agent. |

| IME | Independent Medical Examiner. An IME is a registered health practitioner approved by Worksafe to undertake a medical examination under the WIRC Act. |

| Injured worker | Independent Medical Examiner. An IME is a registered health practitioner approved by Worksafe to undertake a medical examination under the WIRC Act. |

| Medical Panel | An expert panel tasked with providing legally binding answers to medical questions that assists in resolving disputes. |

| Non-compliance | Under WorkSafe’s Self-audit Tool, a failure to meet a workers compensation legislative requirement. |

| Prompted satisfaction | A category of response in an injured worker survey: the response of an injured worker to a question about overall satisfaction asked after other questions about specific aspects of service. |

| Self-insurer | A company (‘body corporate’) approved by WorkSafe under legislation, to manage and fund the workers compensation claims of their employees instead of paying premiums to WorkSafe. |

| Substantiated complaint | Defined by WorkSafe as a complaint where it finds some evidence of a potential breach of the WIRC Act. |

| Unsustainable decision | A decision that does not have a reasonable prospect of withstanding a court challenge. |

| WCIRS | The Workers Compensation Independent Review Service. An independent review team within Worksafe that provides injured workers with a review of some Agent and WorkSafe decisions. Injured workers of self-insurers cannot currently request a review from this team. |

| WIC | When a WIC Conciliation Officer is unable to bring the parties to agreement and considers there to be an arguable case on the part of the self-insurer or their agent. A genuine dispute certificate allows the matter to proceed to arbitration or court. |

| WIC – genuine dispute | When a WIC Conciliation Officer is unable to bring the parties to agreement and considers there to be an arguable case on the part of the self-insurer or their agent. A genuine dispute certificate allows the matter to proceed to arbitration or court. |

| WIC – Direction | When a WIC Conciliation Officer deems that an self-insurer or their agent has no arguable case to deny liability to pay weekly compensation or medical and like expenses to a worker they may direct that limited payments are made. |

| WIRC Act | Workplace Injury Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 2013 (Vic) |

| Workers compensation | A payment to employees injured at work or who become sick as a result of their work. It includes payments to employees to cover their wages while they are not fit for work, medical expenses and rehabilitation. |

| WorkSafe | The trading name for the Victorian Workcover Authority, a statutory authority of the Victorian government created under the Accident Compensation Act 1985 (Vic). |

Background

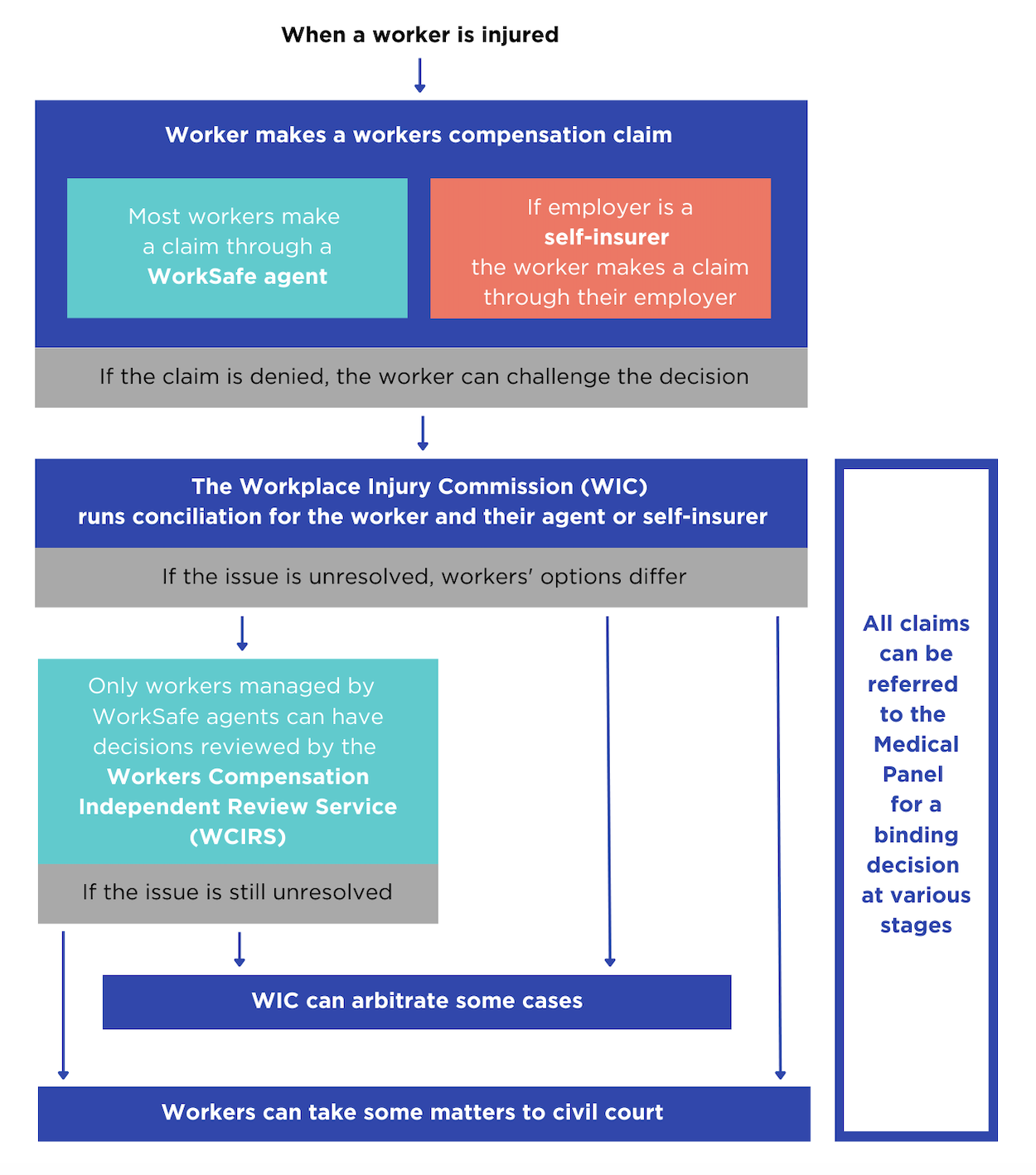

1. Victoria’s statutory workers compensation scheme enables eligible injured workers to claim compensation and receive support to help them recover and, where possible, return to work.

2. The Workplace Injury Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 2013 (Vic) (‘WIRC Act’) outlines a range of entitlements under the scheme, including weekly income payments for those unable to work, and payments to cover reasonable treatment costs.

3. One of the objectives of the WIRC Act is that compensation ‘is paid to injured workers in the most socially and economically appropriate manner, as expeditiously as possible’.

4. The scheme is managed by the Victorian WorkCover Authority (‘WorkSafe’), and operates on a ‘no fault’ basis, meaning employees are covered if they are injured at work, regardless of who is at fault.

5. The scheme is largely funded by compulsory annual insurance premiums paid by employers. In return, WorkSafe takes on liability for most workers compensation claims, outsourcing them to private agents to manage. Four WorkSafe agents in Victoria manage all the claims for about 95 per cent of the cost of the scheme.

6. The WIRC Act also allows for some eligible employers, mostly larger corporations, to run their own separate claims process instead of paying compulsory premiums to WorkSafe. These employers are known as ‘self-insurers’.

7. There are 34 approved self-insurers at the time of writing, covering about 120,000 Victorian workers and including many of Victoria’s largest employers (see full list in Appendix 2).

8. Most self-insurers handle claims in-house; but just as WorkSafe uses private agents to manage claims, some self-insurers also outsource claims management to private agents. Eight self-insurers have WorkSafe approval to outsource the management of some or all of their claims to agents.

9. WorkSafe is responsible for approving and monitoring self-insurers (and their agents) to enforce performance standards and promote good decision-making.

Our prior WorkSafe investigations

10. This is the Ombudsman’s third investigation into the administration of Victoria’s statutory workers compensation scheme. The first two were confined to WorkSafe and its agents, and did not look at self-insurers.

11. Our first report in 2016 looked at how WorkSafe’s agents handled difficult and expensive compensation claims, and WorkSafe’s oversight of them. The report concluded while the system was not broken, the handling of complex claims needed reform. WorkSafe accepted all 15 Ombudsman recommendations, with the support of the responsible Minister.

12. However, over the next few years we continued to receive complaints and heard anecdotal evidence not enough had changed.

13. Our second report in 2019 found some WorkSafe agents were continuing to make unreasonable decisions, leaving workers stuck in time-consuming, stressful and costly disputes. It was evident more systemic reform was needed.

14. We made three key recommendations. First, that the Victorian Government review whether the WorkSafe agent model remained appropriate for complex claims. In response, the Government commissioned Improving the experience of injured workers: A review of WorkSafe Victoria’s management of complex workers compensation claims (‘the Rozen report’), published in April 2021.

15. Second, the Ombudsman recommended the Government address a shortcoming in the dispute resolution system – that only a lengthy and costly court process could deliver a binding outcome where other efforts to resolve a dispute, such as conciliation, had failed.

16. In response, the Government introduced legislation allowing arbitration as an option for injured workers after conciliation. All Victorian workers, including those working for self-insurers, can now seek binding determinations on disputes without having to go to court.

17. Third, the Ombudsman recommended WorkSafe establish a dedicated business unit to independently review disputed decisions following unsuccessful conciliation, and use its existing powers to direct its agents to overturn decisions unlikely to be upheld if challenged in court.

18. In response, the Workers Compensation Independent Review Service (‘WCIRS’) began in 2020. WorkSafe says in its first three years, WCIRS has had a significant impact, with fewer adverse decisions needing to be overturned, suggesting a measurable improvement in the quality of WorkSafe agent decision-making. It is hoped that more injured workers are getting timely and fair outcomes because of this change.

19. However, not all Victorian workers can take their concerns to WCIRS, with injured workers of self-insurers being excluded from using the service.

Figure 1: Victoria’s workers compensation system

Source: Victorian Ombudsman

Why we investigated

20. Following the Ombudsman’s two WorkSafe investigations, we continued to receive complaints from injured workers of self-insurers. Those complaints often echoed those made about WorkSafe agents. People complained about self-insurers making unreasonable claims decisions not supported by evidence.

21. Unions and other stakeholders have criticised the self-insurer scheme. Some criticisms are about the conduct of individual companies, including the use of technical grounds to deny claims, the misuse of medical evidence and a litigious approach to conciliation.

22. WorkSafe’s annual surveys of injured workers from at least 2018 onward consistently show self-insurer workers are about 10 per cent less satisfied than those with claims managed by WorkSafe agents.

23. We received data from the Workplace Injury Commission (‘WIC’). WIC is an independent authority established under the WIRC Act to help resolve workplace compensation disputes. WIC data for the 2020-21 and 2021-22 financial years showed notably lower rates of resolution at conciliation where a self-insurer was involved.

24. WIC told the investigation it had observed positive changes in WorkSafe agent decision-making after the Ombudsman’s second WorkSafe report but this had not flowed through to some self-insurer decision-making. WIC stated some self-insurers were not meaningfully engaging in the conciliation process and were continuing to dispute matters unlikely to be upheld if challenged in court (‘unsustainable decisions’). WIC suggested a lack of improvement by self-insurers in these areas may have been due, in part, to the limits of WorkSafe’s role as regulator.

25. WIC noted injured workers of self-insurers were unable to seek a WCIRS review of a decision. This gap was highlighted by many when we called for public submissions to our investigation, and by the Rozen review. WCIRS cannot review decisions made by or on behalf of a self-insurer, because WorkSafe has no power to direct self-insurers to overturn decisions. This places workers of self-insurers at a disadvantage compared to most Victorian workers.

26. Another theme in complaints to the Ombudsman and submissions to the investigation was WorkSafe’s oversight of self-insurers, and whether it can or does effectively address issues. Half of the 22 submissions that informed the Rozen review highlighted that self-insurers were engaging in the same practices WorkSafe agents had been prior to the Ombudsman’s investigations. In response to these concerns, WorkSafe stated that it was implementing changes to align the review of self-insurer decision-making with that of WorkSafe agents. WorkSafe stated it was not taking any specific action to agitate for the power to overturn self-insurer decisions in response to the Rozen report.

27. Based on all of this – public complaints and submissions to the Ombudsman, the Rozen review and WorkSafe’s response to its report, information from WIC and WorkSafe’s surveys of injured workers – the Ombudsman decided to investigate.

Figure 2: Voices of injured workers

Workers’ experiences with self-insurers varied significantly. These quotes from injured worker surveys describe both positive and negative encounters.

The investigation

28. On 27 May 2022, the Ombudsman notified the relevant Minister, Chief Executive Officer of WorkSafe, Chair of WorkSafe’s Board of Directors and the Chief Executive Officer of the Accident Compensation Conciliation Service (now WIC) of her intention to conduct an ‘own motion’ investigation, under 16A of the Ombudsman Act 1973 (Vic), into self-insurers’ claims management and WorkSafe’s oversight.

29. Between 27 and 30 May 2022, the Ombudsman also notified the Principal Officer of each of Victoria’s 34 self-insurers.

30. On 14 July 2022 the Ombudsman publicly announced her decision to conduct the investigation and called for public submissions.

31. The objective of the investigation was to establish whether the claims management processes of self-insurers provide fair and equitable outcomes for their injured workers and whether the oversight processes of WorkSafe contribute to fair and equitable outcomes for injured workers of self-insurers.

32. Although self-insurers are required to manage claims in accordance with the WIRC Act and adopt the same claims management practices as WorkSafe agents, they have a discretion to take different approaches. The case studies and practice notes in this report highlight only a slice of the varying claims management approaches taken by self-insurers. They are included to encourage all self-insurers and WorkSafe to reflect on industry standards, and whether the current system is delivering fair outcomes and preserving workers’ rights under the Act. Specific self-insurers are not identified in these samples to protect the privacy of the injured workers.

How we investigated

33. The investigation received 45 submissions, including from seven self-insurers, an agent who represented three self-insurers, injured workers and their advocates, lawyers, industry groups, unions and health care providers. Through submissions and other sources, about 240 claim files were identified for possible examination; and 87 of these were obtained from self-insurers and reviewed in detail. Information was also sought from WorkSafe and WIC, and we spoke to 20 injured workers and their advocates.

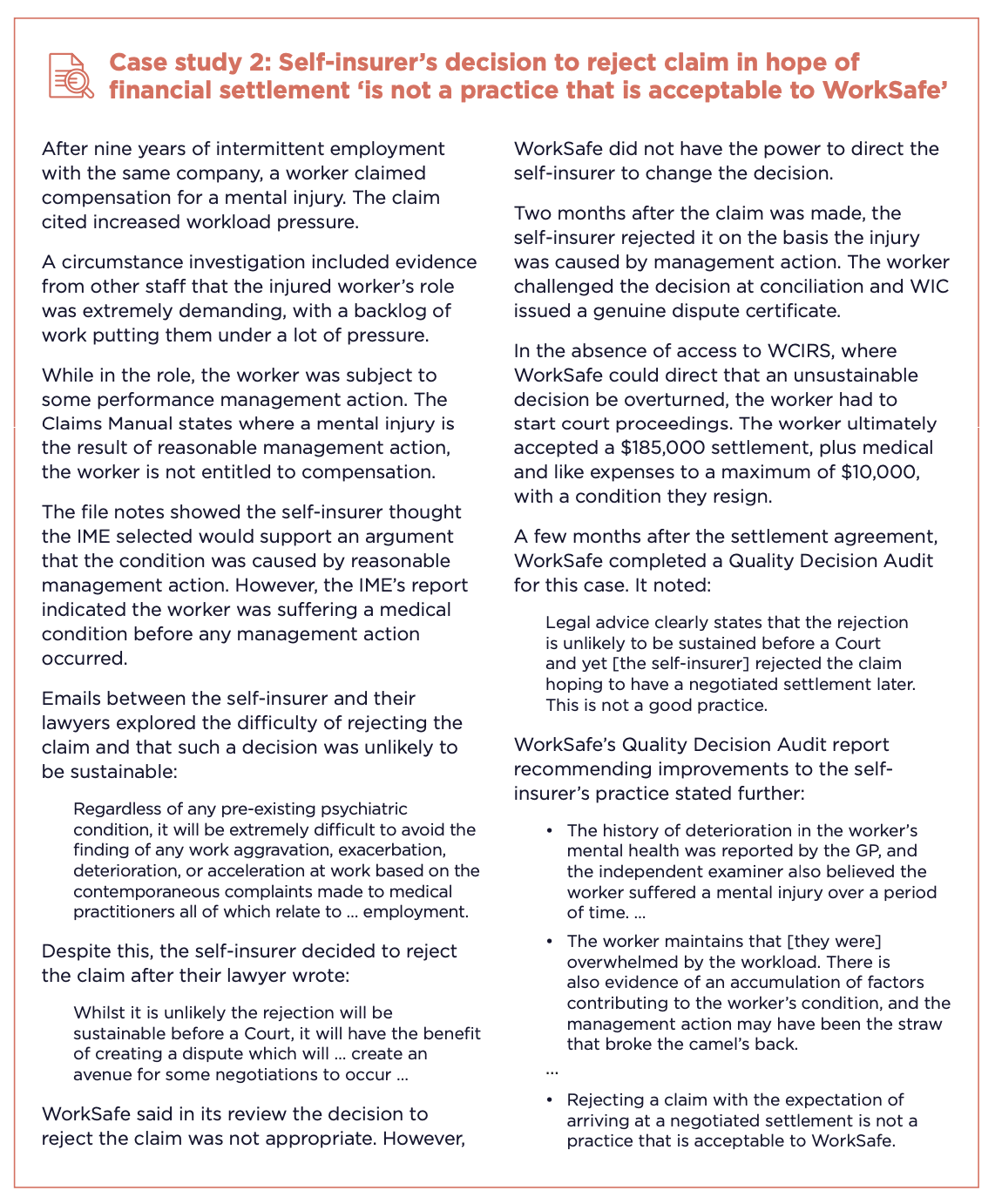

34. In all, the investigation obtained more than 850,000 documents, and reviewed material including:

- selected self-insurer files and correspondence

- data about the outcomes of disputed claims

- examples provided by self-insurers at our request demonstrating best practice

- WorkSafe documents, including processes, guidelines and assessments of self-insurer performance

- WIC data, files, and feedback about the participation of self-insurers at conciliation.

35. Further details about what the investigation examined are included in Appendix 1.

Procedural fairness and privacy

36. The investigation is guided by the civil standard of proof, the balance of probabilities, in determining the facts of the investigation – taking into consideration the nature and seriousness of the matters examined, the quality of the evidence, and the gravity of the consequences that may result from any adverse opinion.

37. This report includes adverse comments about WorkSafe as the regulator of self-insurers. While the Ombudsman has not made adverse comments or conclusions about specific self-insurers, or their agents, it does include data, practice examples and comments from third parties, including injured workers, about claims management that may be perceived as adverse to self-insurers.

38. In accordance with section 25A(2) of the Ombudsman Act, the investigation has provided WorkSafe, each of the 34 self-insurers, and two agents who act for self-insurers, with a reasonable opportunity to respond to the material in the report. This report fairly sets out their responses.

39. Relevant excerpts of a draft of this report (‘the draft report’) were provided to the injured workers whose stories are detailed in de-identified case studies and to WIC, to confirm factual accuracy. Self-insurers were also provided with excerpts of the case studies to confirm factual accuracy. This report fairly reflects their responses.

40. In accordance with section 25A(3) of the Ombudsman Act, any other persons or bodies who are or may be identifiable from the information in this report are not the subject of any adverse comment or opinion. They are named or identified in the report as the Ombudsman is satisfied that:

- it is necessary or desirable to do so in the public interest

- identifying those persons will not cause unreasonable damage to those persons’ reputation, safety or wellbeing.

41. To protect the privacy and welfare of injured workers, case studies in the report exclude identifying details such as employer names and dates. All case studies relate to claims made between 2016 and 2022.

42. In response to the draft report, some self-insurers provided detailed responses to specific points which are incorporated in the final report. The names of self-insurers are used in these instances as they do not identify individual workers.

43. It should not be inferred that claims management practices or decisions made on an individual case highlighted in this report reflect a self-insurer’s or their agent’s approach or performance in other cases. Some self-insurers manage many claims, and most are handled without complaint or necessary intervention from WorkSafe.

44. Nevertheless, it is important that injured workers’ stories are heard, and their experiences valued and understood. From the 87 workers’ stories examined in detail, the case studies we have included were chosen to reflect questionable or problematic claims management practices, and their adverse impacts. Some case studies were removed from the final report at the request of the injured workers who said they were still affected by the management of their claim, or were fearful of reprisals.

45. Any of us can be injured at work, and we are all entitled to expect best practice in response. All self-insurers and their agents can learn from the case studies and practice examples in this report. Adherence to best practice leads to appropriate compensation as intended by the WIRC Act.

About the self-insurer scheme

46. WorkSafe’s website states the role of self-insurance in Victoria is to ‘provide choice to eligible employers to manage and bear the costs and risks of their own claims’. WorkSafe advises self-insurance should:

- provide direct incentives to improve injury prevention and rehabilitation performance

- ensure that workers are treated fairly and equitably

- contribute to continuous improvement in health and safety and return to work performance.

47. In the financial year ending June 2022, 1,713 claims were lodged with self-insurers. Unlike some of its interstate counterparts, WorkSafe does not publish claim numbers or statistics, however WorkSafe advised the investigation that self-insurers were managing 3,032 active claims at the end of December 2022.

48. WorkSafe is responsible for approving self-insurers under the WIRC Act. WorkSafe first determines if the company is eligible. This includes whether the company has the financial viability to meet its claims liabilities.

49. To be satisfied that a company is ‘fit and proper’ to be a self-insurer, WorkSafe must also consider:

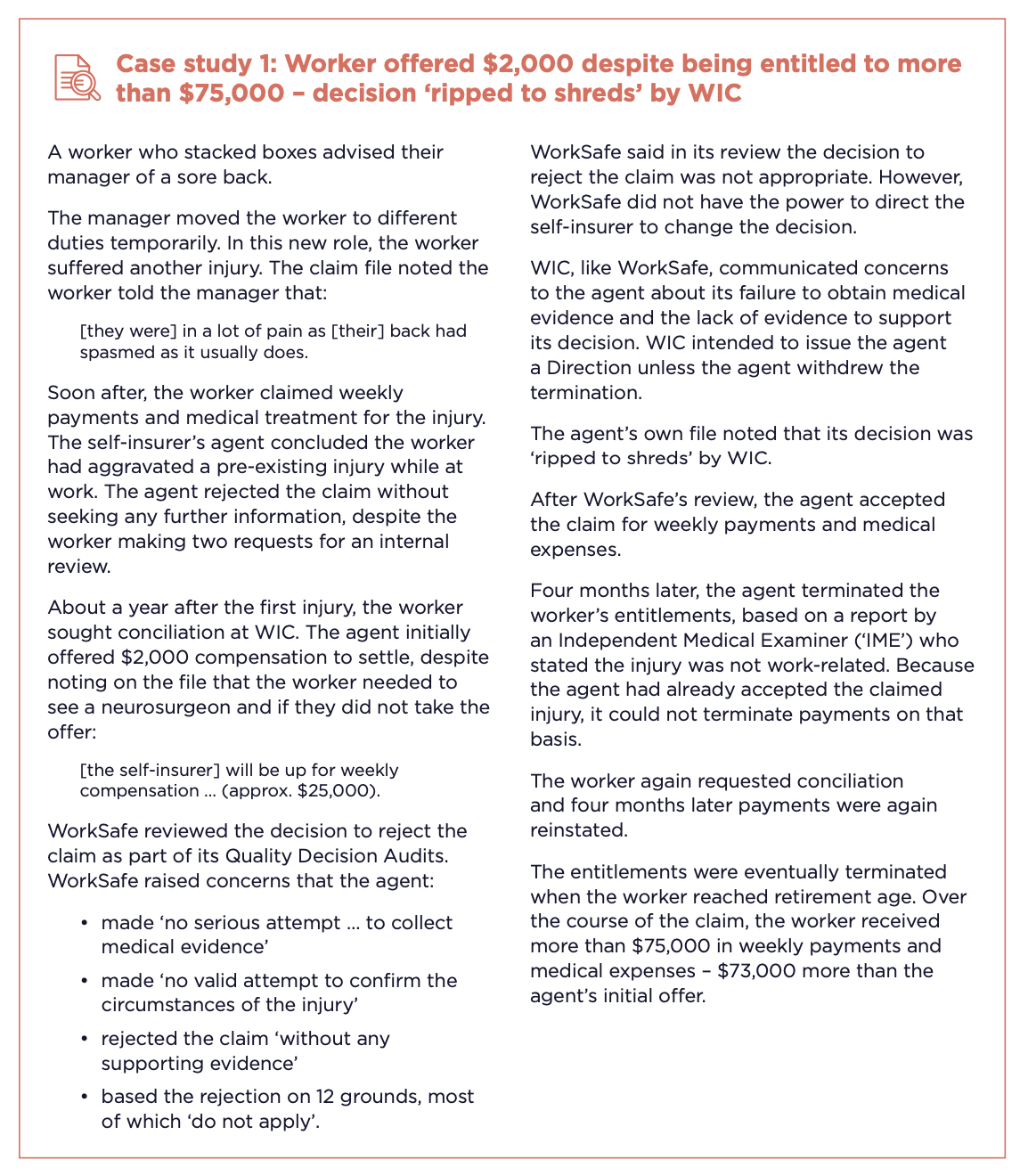

- the safety of working conditions at the company

- the number of workplace injuries

- the cost of associated claims

- the resources, including employees, the company has to administer compensation claims.

50. WorkSafe’s oversight framework is based on the WIRC Act and associated Ministerial Orders and WorkSafe Guidelines. WorkSafe regulates self-insurers using:

- a ‘tier’ system

- the Self-insurer Self-audit Program

- a Regulatory Claims Audit Program

- post-audit performance improvement plans

- monitoring and reporting systems.

51. WorkSafe also conducts Quality Decision Making Audits (‘Quality Decision Audits’) of both WorkSafe agent and self-insurer decisions. A sample of claims decisions are reviewed every year to confirm alignment with good decision-making principles and the law. The audits focus on compliance with WorkSafe’s Claims Manual and Quality Ethical Decision-Making Guidelines.

52. The Quality Decision Audits consider whether reasonable and appropriate evidence was sought and considered, whether the decision was correct in the circumstances, and whether it was ‘sustainable’. Decisions are considered unsustainable if they do not have a reasonable prospect of withstanding a court challenge.

53. When there is a dispute about a claim, the matter can be conciliated through WIC. This is true regardless of whether a WorkSafe agent or a self-insurer is managing the claim.

54. WIC is an independent authority responsible to the Minister for WorkSafe and the TAC and reports through the Department of Treasury and Finance.

55. WIC’s website states conciliation gives an injured worker ‘the opportunity to come together with others involved in a workplace compensation dispute to find a way forward as quickly as possible’.

56. The goal of conciliation is to resolve disputes by involving all parties in an informal, non-adversarial process to reach a fair and mutually acceptable agreement. Ministerial Guidelines govern the conduct of self-insurers and employee representatives during the conciliation process.

57. In 2021-22, workers referred 9,182 disputes in total to WIC for conciliation, with resolution rates of 69 per cent for WorkSafe agents and 58 per cent for self-insurers (and their agents).

58. Where a matter cannot be resolved, Conciliation Officers have the power to:

- dismiss the dispute

- make recommendations

- refer medical questions to a Medical Panel

- issue a ‘genuine dispute certificate’.

59. A genuine dispute certificate is needed before the parties can take the matter to arbitration or court. In limited circumstances, Conciliation Officers also have the power to give a Direction to a WorkSafe agent or a self-insurer to make payments to the worker.

60. Some disputes are referred to a Medical Panel for a determination on medical questions. Medical Panels can be used by WIC or a court to resolve a dispute where there are medical questions regarding a worker’s injuries. These questions may relate to diagnosis, causation, work capacity or the appropriateness of treatment.

61. Each Medical Panel is independent and made up of expert specialist doctors. The Panel functions as a tribunal that provides final and legally binding answers to the medical questions referred to it.

62. In 2021-22, WIC referred 1,151 matters to Medical Panels. About 14 per cent (163) of these were for claims involving self-insurers.

63. If conciliation is unsuccessful and a genuine dispute certificate issued, injured workers now have two potential options.

64. Until recently their only choice was to go to court. Workers injured on or after 1 September 2022 now have an option for the matter to be arbitrated by WIC under the Workplace Injury Rehabilitation and Compensation Amendment (Arbitration) Act 2021 (Vic).

65. This is a welcome system improvement, however, not all disputes are eligible for arbitration.

66. Arbitration can only provide a final decision on compensation disputes involving weekly payments, medical expenses, superannuation contributions and interest on an outstanding amount. In other cases, the worker’s only option remains court.

67. As the regulator, WorkSafe has a role to support self-insurers to understand their obligations under the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) (‘Charter of Rights Act’).

68. This Act protects basic rights and freedoms of Victorians, such as the right to privacy and reputation. It promotes a culture where human rights are protected and considered in service delivery, policy, decisions, and legislation.

69. Under the Charter of Rights Act, it is generally unlawful for public authorities to:

- act in a way that is incompatible with a human right; or

- fail to give proper consideration to a relevant human right when making a decision.

70. Public statutory bodies, like WorkSafe, must act compatibly with, and give proper consideration to, relevant human rights when making decisions. Self-insurers, when licensed by WorkSafe to perform functions under the WIRC Act, are also required to consider these rights. The Charter of Rights Act recognises that human rights are not absolute and may be limited but any limitation must be reasonable and justified.

Self-insurers’ claims management

71. In Victoria, self-insurer decision-making on claims must be guided by the WIRC Act and the WorkSafe Claims Manual, which sets out principles of good administrative decision-making. Although it is permitted for Victorian self-insurers to create their own claims management policies, in practice, all Victorian self-insurers have adopted the WorkSafe Claims Manual as their baseline for claims management.

72. These principles include that self-insurers must:

- make decisions in accordance with the legislation and follow the procedures in the Claims Manual

- consider all matters relevant to a decision

- not take into account any irrelevant considerations

- exercise discretion when appropriate

- use the best available evidence

- seek out information if it is relevant to the decision, or the information available is inadequate

- give ‘proper, genuine and realistic consideration’ to the merits of a decision

- list all matters considered when making a decision.

73. The Claims Manual also provides guidance to self-insurers on key claims management activities, including:

- determining liability

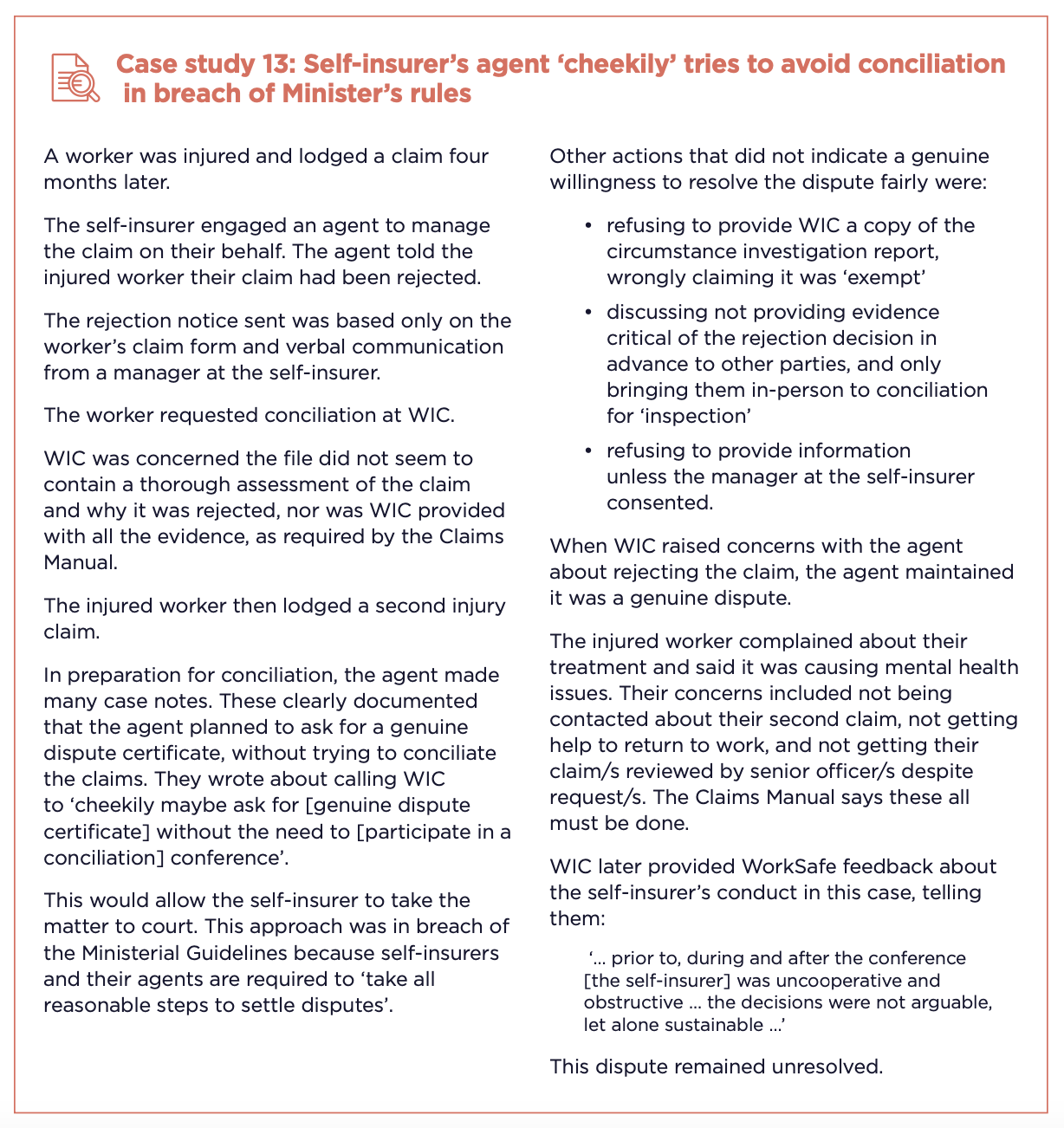

- following a sound decision-making process

- arranging independent medical examinations and investigations

- processing weekly payments

- terminating weekly and medical payments.

74. WorkSafe’s External Guideline #16 – Claims management policies for self-insurers says that ‘self-insurers must ensure workers are not disadvantaged and will continue to receive at least the same level of entitlement as prescribed in the [Claims] Manual’.

75. Self-insurers also have the option of appointing an agent to manage claims on their behalf. Some companies do this, arguing it provides the best of both worlds for injured workers – the expertise of dedicated claim experts, the industrial knowledge of the employer and streamlined decision-making.

76. Where an agent is appointed, it is the self-insurer's responsibility to ensure that the agent abides by the legislation and the Claims Manual. As the case studies in this report illustrate, poor practice by self-insurer agents can occur when the self-insurer does not fulfill this responsibility.

77. Occupying the position of both employer and insurer creates a significant power imbalance between self-insurers and their workers. This potentially discourages some workers from reporting injuries or making claims.

78. Some self-insurers, like TLC Aged Care, advised they took their role as a self-insurer extremely seriously because of this perceived inequity. Department store operator Myer added that unions can and do play a role in addressing any imbalance. Investigators nevertheless heard accounts of workers who feared for their job if they pursued their compensation entitlements. In some instances, they said that fear was based on what they saw happen to colleagues. Others said they were told directly. Such fears and practices are not limited to self-insurers, but the vulnerabilities of the injured worker are amplified when dealing directly with their employer.

79. The investigation spoke to injured workers of self-insurers who said they were discouraged from or penalised for making a claim. Steel producer BlueScope suggested more claims would be captured by adopting a NSW-style system and placing the onus on self-insurers to proactively contact workers on reporting of an injury to advise of early access to provisional payments and medical treatment.

Resolving claims early

80. There are various ways claims can be resolved early. The investigation was told some methods discourage potential claims from being made.

81. Self-insurers, along with other employers in the WorkSafe scheme, can offer to cover an employee’s medical expenses without the need for a claim. This may meet the worker’s immediate needs and avoid a claims process. As some self-insurers acknowledged, not lodging a claim could leave the worker with limited recourse if their injury or condition did not resolve as anticipated and required ongoing treatment or time off work.

82. Evidence obtained showed that some self-insurers asked injured workers to use their own sick leave instead of putting in a claim. This shifts liability from the employer to the employee, undermining the intent of the workers compensation scheme.

83. The investigation also noted evidence showing some self-insurers offered financial settlements and used internal early intervention programs to resolve claims.

Financial settlements

84. With financial settlements for 'common law damages' often involving long and expensive legal proceedings, there are instances where a self-insurer and workers might prefer to reach an early agreement for a lump-sum payment. The Australian Lawyers Alliance said:

Unlike WorkSafe agents, self-insurers take a proactive approach … and initiate early discussions with injured workers regarding common law damages. These discussions often result in the negotiation of a global settlement which can provide the worker with compensation for their pain and suffering, pecuniary loss and in some circumstances their future medical expenses …

Importantly, it also represents to workers the taking of responsibility by an employer for the occurrence of an injury which serves as an acknowledgement of the harm caused. This early resolution has a positive outcome and benefits the injured worker.

85. Some submissions raised concerns about self-insurers’ use of financial settlements. WIC stated that under the legislation there is only capacity to settle a common law claim for pain and suffering and losses that can be measured in monetary terms. This may not include all possible costs to the injured worker. Submissions consistently raised concern that settlements sometimes followed decisions to terminate entitlements that were not well supported by evidence. It was also suggested workers may be disadvantaged because lump-sum payments were usually conditional on the employer not being held liable for the claimed injury in future proceedings.

86. Self-insurers defended the use of financial settlements. Some claimed workers must be legally represented in certain circumstances. Myer, for example, said a settlement offer that permanently ceases a worker's entitlements under the WIRC Act would require legal representation so the worker can get advice to redress any power imbalance. The WIRC Act does not contain a provision that requires this.

87. Sometimes an injured worker seeks the settlement. Westpac bank told the investigation it was involved in:

numerous cases where the employee is seeking financial settlement, based on independent legal advice and/or advice from their treating medical practitioner, especially where the case involved some psychological distress.

88. When workers are injured, financially vulnerable and possibly in fear of losing their job, a lump-sum payment can appear attractive. Accepting such a settlement could leave the worker without ongoing entitlements and may be to their longer-term detriment.

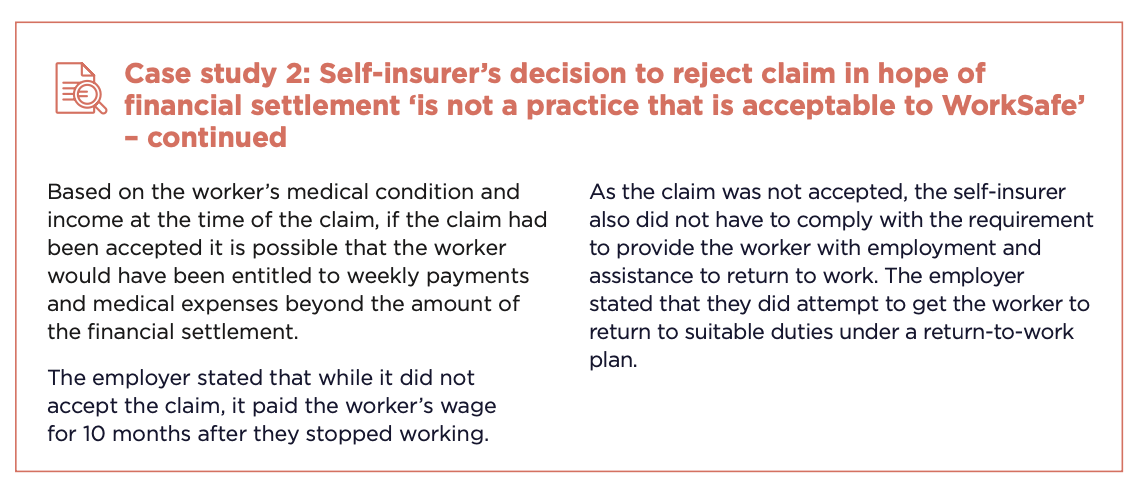

89. WIC outcomes data shows a large variance in how self-insurer disputes are finalised compared to those of other workers. Between January 2018 and June 2022, WIC issued a genuine dispute certificate due to court proceedings in 16 per cent of self-insurer cases, compared to 0.4 per cent of cases for other workers. This means many more self-insurer disputes were not actively conciliated. These disputes then either proceeded to court or in many cases were finalised prior to court by financial settlement.

90. Often a settlement is conditional on the worker resigning. There may be valid reasons for such a condition, and the worker may have no capacity or desire to return to work. The injured worker may believe their relationship with their employer has broken down. However, pressuring a worker to resign in order to access compensation could amount to a breach of the WIRC Act if it is not legitimate, as the Act is intended to support workers to return to work.

91. Myer stated self-insurers tended to continue the employment of injured workers for extended periods often up to the time the matter was settled, which could be many years after the injury. It submitted the inclusion of a resignation condition was merely a reflection that, at settlement, the employment relationship ceased. This approach does not appear unique to self-insurers.

92. Paying a settlement may be preferred by a self-insurer if it costs less than paying a worker weekly compensation payments and associated expenses long term. This may not be beneficial to the injured worker, and they should have access to all options and understand the risks and benefits to make an informed decision. BlueScope agreed stating ‘it is imperative injured workers be assisted to negotiate in a complex, legalised system’.

93. Anecdotally, it is suggested financial settlements are sometimes made in the absence of a claim. This was not directly examined by the investigation, and the frequency of such settlements is unknown. Given financial settlements are not independently scrutinised, and WorkSafe would have limited jurisdiction over settlements made prior to a claim (unless practices contravened the WIRC Act) this issue warrants further examination to ensure injured workers are protected. It is important settlements made outside of the formal claim process do not contravene the purpose or provisions of the WIRC Act.

94. Case study 1 provides an example of a worker being offered a settlement which if accepted would have disadvantaged the worker by tens of thousands of dollars.

95. Case study 2 provides an example of a self-insurer rejecting a claim to create an avenue for negotiations with the injured worker for a financial settlement. WorkSafe has criticised self-insurers for this practice.

Employer-funded early intervention programs

96. Some self-insurers provide early intervention programs, designed to support staff during the injury management process and improve return to work outcomes. The investigation does not criticise these programs in principle, but we did identify instances where they featured in poor claims management.

97. Each early intervention program is different, but typically includes some form of employer-funded medical services for injury treatment. Some programs provide access to a network of general practitioners, while others have on-site medical and allied health practitioners for timely treatment of minor injuries. Some include support for psychological injuries.

98. Supermarket operator Woolworths launched an early intervention program, including access to clinical specialists and mediation for ‘difficult conversations’ to minimise claim impacts for both the employer and employees. Conglomerate Wesfarmers advised it had adopted a ‘best practice mental health care model’ that:

puts the team members health and wellbeing at the forefront whilst claims management decisions are managed in the background …

[While we recognise] claims for entitlement must be assessed and evaluated rigorously, they need to be balanced with the care owed to team members.

99. Supermarket operator Coles and airline Qantas told us they often prefer to deal directly with workers’ treating practitioners to:

- facilitate timely and ongoing clinical care and rehabilitation

- better understand worker needs

- develop suitable and sustainable return to work options.

100. Self-insurers who provided information about their programs – Qantas, gaming and entertainment group Crown, automobile club RACV, Westpac, Coles, BlueScope, Woolworths and their agent Employers Mutual Ltd (‘EML’) – all emphasised the benefits of early intervention for employees and employers alike. Some focused on the benefits of early access to specialist care including surgery, and many highlighted the importance of compassionate and supportive communication. RACV and Westpac highlighted the contribution of these programs to best practice return-to-work outcomes.

101. Payment of an injured worker’s medical costs and referral to rehabilitation and support services by a self-insurer frequently occurs outside the claims management process because no claim has yet been, or is ever, lodged.

102. Case study 3 provides an example of workplace support and intervention working well.

103. Despite obvious advantages, there are ways in which this model can, by accident or design, produce an unfair outcome.

104. To obtain workers compensation, workers must notify their employer within 30 days of becoming aware of an injury, and must make a claim for weekly payments as soon as practicable. If an injured worker is channelled into an internal rehabilitation program their injury may not resolve as hoped. If they are later denied a claim for this injury based on lodging too late, this is unfair.

105. While some self-insurers accept claims beyond deadlines, the investigation saw several examples of workers’ claims being rejected as ‘out of time’, despite the worker receiving treatment through an internal rehabilitation scheme. Self-insurers should consider all evidence indicating a possible workplace injury irrespective of whether a claim was lodged at that time, as it is reasonable to attempt early interventions without a formal claim.

106. BlueScope advised the investigation early intervention or other programs should not be provided in lieu of a claim being lodged by the injured worker, and that workers must always retain the right to lodge a claim. Myer and Crown agreed and told the investigation their workers are specifically told they retain the right to submit a workers compensation claim after accessing early intervention programs.

107. Case study 5 provides an example of a worker signing away their rights to make a claim when accepting early intervention services. Self-insurers should be wary of asking workers to sign documents that may limit the employee’s rights because as employers they are in an inherently conflicted position to provide advice. Employees should always be provided with accurate information so they can understand their options and give informed consent.

108. While WorkSafe provides WorkCover Assist, a free service to help injured workers with a claims dispute, this is only available when that dispute is referred to WIC for conciliation.

109. In Victoria the early intervention model may in part offset the absence of ‘provisional payments’ for all but mental injuries. The NSW provisional payments system is broader, enabling self-insurers to make weekly payments and cover medical expenses while an injured worker’s claim is assessed.

110. BlueScope advocated for provisional payments to be expanded in Victoria, and stated:

… it negates payment for treatment external to the workers compensation system and captures claims under the legislative framework. The additional cost to insurers would amount to less than 5 per cent of current claim costs and provide certainty for injured workers.

111. It also noted the provisional payment system ‘reduces considerably the wait-time for injured workers to seek treatment’.

Rejecting and terminating claims

112. The investigation found examples of self-insurers rejecting or terminating claims without sufficient evidence to support the decisions.

113. In some instances, self-insurers did not take remedial action when WorkSafe notified them of these problems.

Rejecting claims

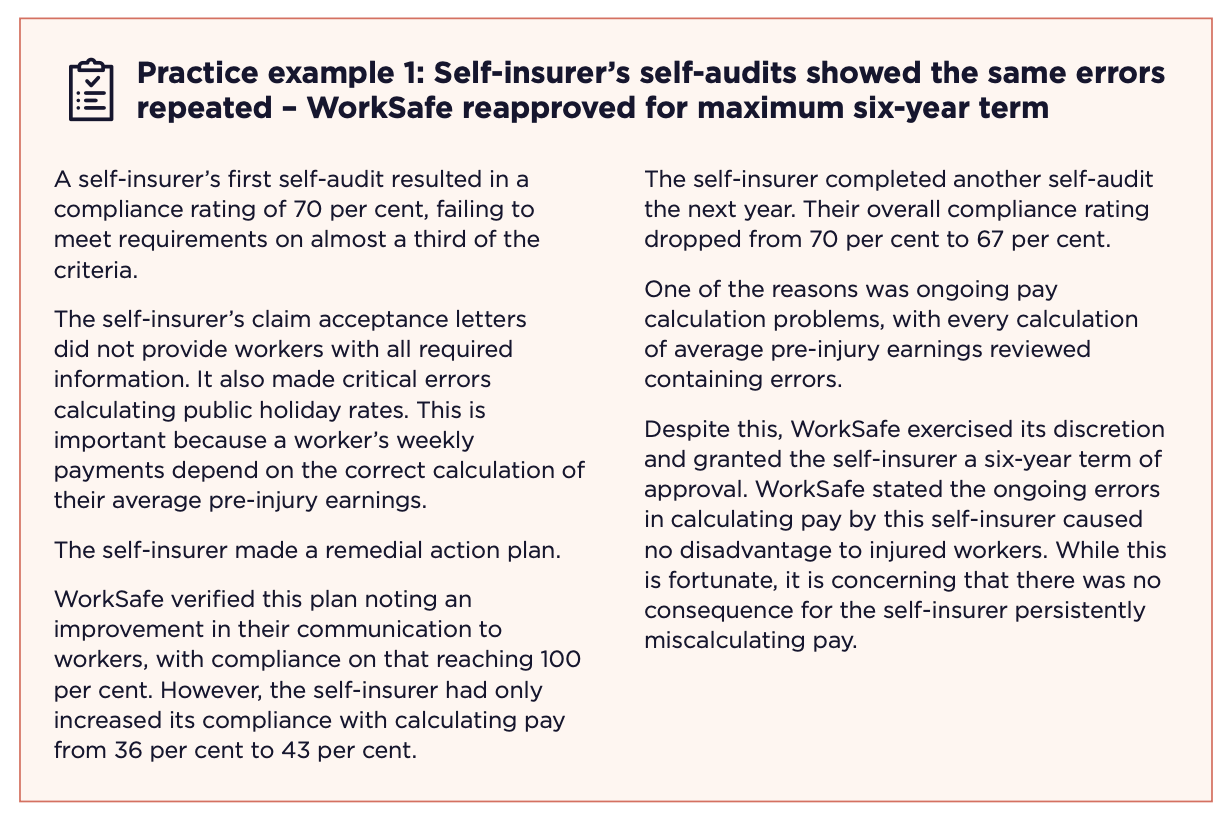

114. In 2019, WorkSafe’s Quality Decision Audits found 25 per cent of the rejection decisions audited were not supported by evidence or otherwise unsustainable. It is not clear if these wrong decisions were driven by financial imperatives or were practice or capability issues.

115. In some of the cases, the grounds used to deny a claim did not apply to the worker’s situation. In others, there was simply no evidence to support the decision. The cases where self-insurers maintained these decisions after WorkSafe or WIC told them the decision was contrary to law, demonstrate a need for WorkSafe to be empowered to direct self-insurers to overturn their decisions.

Terminating claims

116. Similarly, investigators saw examples of claims being terminated on unsustainable grounds and self-insurers refusing to overturn their decisions despite advice they were wrong. We also saw positive examples of self-insurers helping injured workers years after they had left the workplace.

Using evidence appropriately

117. Medical evidence and other reports are used both to determine the initial validity of a claim, and to inform ongoing assessments.

118. The Claims Manual requires that self-insurers must:

… take all reasonable steps to seek, obtain and to fairly and properly consider all relevant information before making a decision based on the facts and the merits of the individual case.

119. However, the investigation found examples where self-insurers did not seek appropriate evidence or appear to give it the necessary weight when making decisions.

120. It can be challenging to determine the appropriate weight to give evidence, especially if experts disagree or the right specialist to make an assessment is unclear. All evidence should be examined objectively and not used selectively.

Seeking and assessing the right evidence

121. Some cases reviewed showed self-insurers did not seek sufficient evidence to make an informed decision. This included not seeking or selectively seeking medical reports, vocational assessments to inform job options, or circumstance investigations to determine facts or credibility. These requirements are clear in the Claims Manual, with section 104 of the Act also codifying employer obligations around the return-to-work process.

122. WorkSafe’s Quality Decision Audits showed decisions can be unsustainable because of lack of evidence. In some cases, WorkSafe directly raised concerns with self-insurers that ‘reasonable steps were not taken to seek and obtain relevant information’. In others, WorkSafe found that the available information was not properly considered.

123. In many cases self-insurers disagreed with WorkSafe’s findings, such as these findings from WorkSafe audits conducted between 2019 and 2022:

- The medical evidence does not fully support termination … the psychological secondary is not taken into account at all …

- The decision to terminate weekly payments is based on inadequate evidence and the psychological condition is not assessed at all which makes the decision to terminate [medical expenses] unreasonable. Overall, the decision and evidence gathering is not aligned with WorkSafe’s decision making framework …

- There has been no attempt to assess whether the request is reasonable and necessary … the decision is not supported by evidence and is not appropriate …

124. Case study 7 illustrates how failing to properly obtain, comprehend or give appropriate weight to evidence can lead to poor decisions and detrimental outcomes for injured workers.

125. The importance of obtaining key evidence to inform and support decisions, especially when terminating entitlements, cannot be overstated. BlueScope told the investigation that ‘it would be fairer to say the case studies cited most likely reflect difference of opinion on the collected evidence’. This does not reflect what the investigation found.

126. The investigation examined cases where WorkSafe was critical because workers were not assessed properly: the right specialists were not engaged (eg pain specialists) or there was no expert vocational assessment to identify suitable job options.

127. The case studies demonstrate the need for WorkSafe to be empowered to direct a self-insurer where they have not met their obligations to the injured worker. Active follow-up by WorkSafe is also required where WorkSafe or WIC find that a self-insurer does not understand the law or their obligations to injured workers. The lessons from these case studies should be applied to other claims.

Assessing medical opinions

128. Claims decisions should be based on independent medical opinions. The quality of a medical assessment will be influenced by the quality of the referral seeking it.

129. Investigators were told of ‘doctor shopping’ – instances where self-insurers sought opinions from a variety of IMEs, or only from a preferred IME, seeking an opinion favouring a decision to reject or terminate a claim.

130. Further, it was alleged self-insurers sometimes contacted treating practitioners directly to try to influence the information provided.

131. Given the small number of claims examined in depth by the investigation, this report does not suggest such practices are commonplace. To avoid influencing decisions, or the perception of such, self-insurers should ensure that suitable specialists are engaged, all evidence is carefully considered and that when seeking reviews, claims managers do not deliberately or inadvertently attempt to lead the assessor in a certain direction.

Factual and credibility disputes

132. Various submissions raised concerns about self-insurers focusing on the credibility of the claimant rather than the credibility of the claim, by not properly investigating disputes of fact through circumstance investigations.

133. Claims were also made that self-insurers or their agents sometimes raised factual disputes despite credible medical and other evidence that a workplace injury had occurred. In some cases, this was to reject a claim outright. In other situations, it was alleged this was to circumvent a referral to a Medical Panel.

134. In one case examined, the self-insurer stated the injured worker had ‘credibility issues’ as they had not advised of pre-existing injuries when employed. WIC raised concerns about the self-insurer’s decision to reject the claim in this case, given the actions of the claimant and all the medical evidence (including two IME reports) supported that the injury occurred at work.

Medical Panel opinions

135. The Medical Panel is an expert panel of specialist doctors who come together to resolve medical questions if there is disagreement or uncertainty under workers compensation and personal injury legislation. Referrals to the Medical Panel can be made by WorkSafe and its agents, conciliation and arbitration officers from WIC, and self-insured employers. A Medical Panel cannot be used where there are unresolved factual issues.

136. Section 313(4) of the WIRC Act notes that:

For the purposes of determining any question or matter, the opinion of a Medical Panel on a medical question referred to the Medical Panel—

(a) is to be adopted and applied by any court, body or person; and

(b) must be accepted as final and conclusive by any court, body or person—

irrespective of who referred the medical question to the Medical Panel or when the medical question was referred.

137. Self-insurers most commonly interact with Medical Panels because of WIC referrals. WIC notes that a Medical Panel opinion is final and binding on all parties, and that WIC will issue an outcome certificate which reflects the Medical Panel’s opinion. The opinion may only be challenged in the Supreme Court if a party believes there are errors of law.

138. In some cases, we saw self-insurers following the directions of the Medical Panel as they are supposed to. Case study 9 was submitted by the self-insurer to the investigation as a best practice example.

139. WIC claimed some self-insurers are reluctant to refer to Medical Panels, or create factual disputes as these prevent a referral. This approach to finalising referrals, or refusal to subsequently accept a legally binding opinion, causes delays for injured workers.

Participating in conciliation

140. WIC was designed to provide injured workers and their employers with easy access to free, independent and impartial conciliation and arbitration services. Disputed decisions by WorkSafe agents or self-insurers must go through conciliation at WIC before they can be challenged in court.

141. Binding Ministerial Guidelines in Respect of Conciliation require self-insurers to engage in conciliation meaningfully and genuinely and take all reasonable steps to resolve disputes by:

- providing all relevant information prior to a conciliation conference

- attending the conference

- meaningfully and genuinely discuss all relevant issues raised

- only maintaining decisions which have a reasonable prospect of success, were they to proceed to arbitration or court.

142. Where a dispute cannot be resolved at conciliation, the Conciliation Officer may either certify there is a ‘genuine dispute’ (in which case the dispute may proceed to court) or, if they are satisfied that there is no arguable case for denying payment, give a Direction that weekly payments or medical expenses be paid to the injured worker.

Disputes not resolved

143. The aim of conciliation is to resolve a dispute: this usually means varying the original decision by agreement or recommendation.

144. Self-insurers are over-represented in the number of disputes taken to conciliation. Between January 2018 and June 2022 WIC received 47,663 disputes. Of those, 13 per cent were about the decisions of self-insurers. WorkSafe says that self-insurers account for approximately 6 per cent of new claims lodged annually.

145. Workers of self-insurers are also less likely to get a resolution at conciliation, with WIC data showing fewer self-insurer decisions are voluntarily changed compared to those by WorkSafe agents.

146. Between January 2018 to June 2022 WIC issued 17,334 genuine dispute certificates. Of those, 18 per cent were issued for self-insurer claims.

147. Between January 2018 to June 2022 WIC issued 46 Directions. Of those, 30 per cent were issued to self-insurers.

148. Self-insurers offered reasons other than resistance to conciliation to explain these differences. Crown stated fewer resolutions at conciliation could be because self-insurer decisions ‘are more sound, better informed, and defensible’.

149. Construction supplier Hanson submitted that self-insurers were more likely than WorkSafe agents to make and maintain an adverse decision in a complex matter. Hanson’s view is self-insurers (in contrast to WorkSafe agents) often use one person to manage a case for the life of the claim and this person has detailed knowledge which assists them and leads them to maintain the decision at conciliation, which they believe to be correct.

150. Good administrative decision-making should guide all phases of claims management. Detailed knowledge of a claim should be used, in accordance with the Ministerial Guidelines, to engage meaningfully in conciliation and to take all reasonable steps to resolve disputes. Decision-makers should not be resistant to changing their decisions when the merits of the case warrant.

151. Data reviewed by the investigation shows self-insurers make proportionally more decisions that are disputed, and are less likely to successfully conciliate those disputed decisions.

Adversarial approach

152. Submissions to the investigation spoke about an adversarial and combative approach by some self-insurers at conciliation. People complained of an overly litigious mindset and refusals to alter decisions which had little reasonable prospect of being upheld in court.

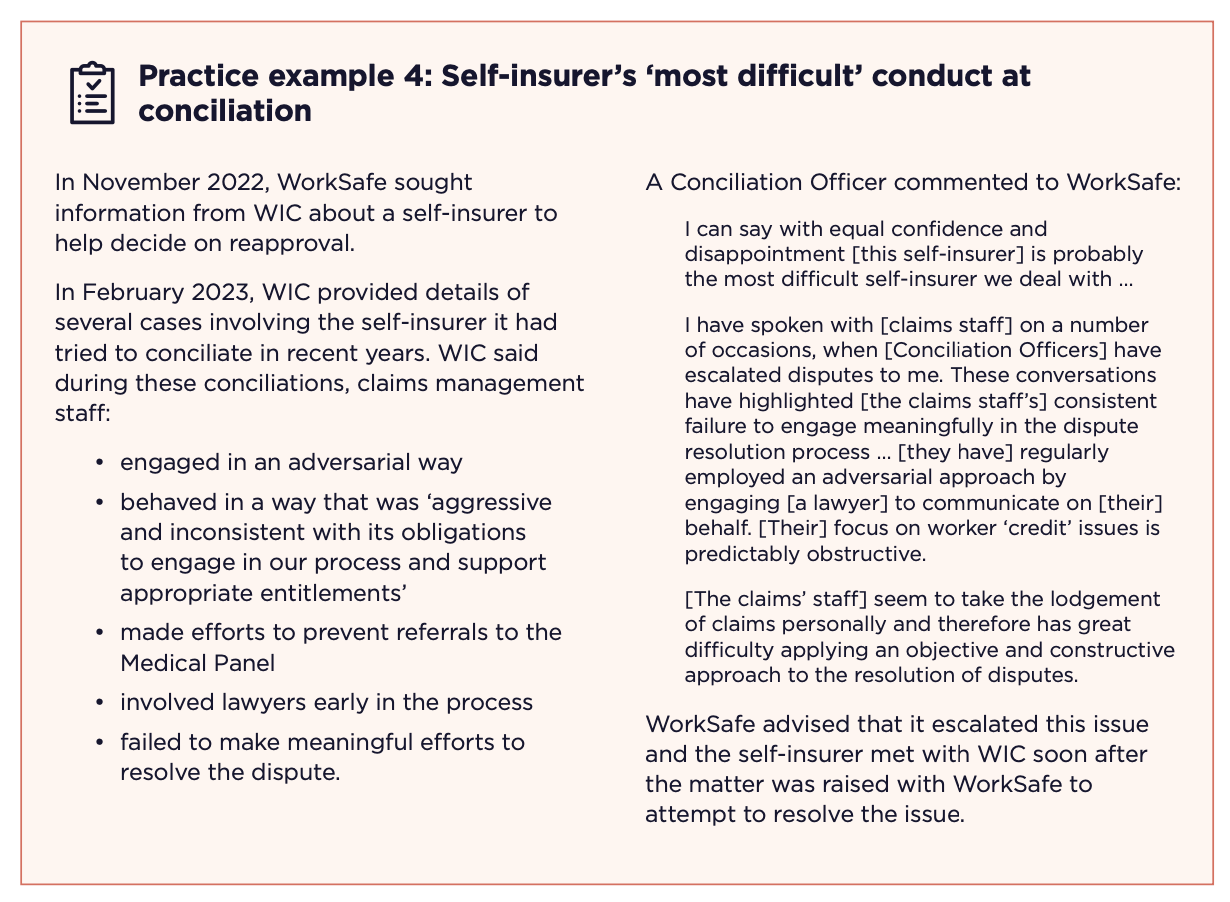

153. WIC told the investigation some self-insurers approached claims management and dispute resolution with a litigious mindset, regardless of the merits of the case or the information available. WIC expressed concern these self-insurers seemed to disregard the alternative dispute resolution objectives set out in the WIRC Act. Unsurprisingly, some self-insurers directly objected to these assertions.

154. Some self-insurers said WIC and litigation were necessary avenues for the small number of complex claims which required legal interpretation. They acknowledged concern about some of the problematic conduct by self-insurers reported at WIC, and distanced themselves from such conduct. Some expressed pride in their meaningful engagement and professionalism at conciliation, and called for further examination of conduct issues and for them to be addressed directly with the self-insurers involved.

155. Other self-insurers alluded to problems they experienced with conciliation. One claimed its representatives felt considerable pressure from Conciliation Officers to change its decisions.

156. Another suggested WIC may not have a good understanding of the challenges self-insurers faced at conciliation, so further education may be beneficial.

157. WIC observed self-insurers tend to have the original decision maker as their representative at conciliation. This is supported by Hanson’s observation that the same person who has managed the case is more likely to maintain the adverse decision. This contrasts with the approach taken by WorkSafe agents, where a trained dispute resolution officer will attend, often with ‘fresh eyes’ and potentially more openness to alternative options.

158. WIC stated when decisions or attitudes obstructed an injured worker’s access to a genuine early dispute resolution process this impacted the most vulnerable who were less willing or able to pursue their matter in court.

159. The power and resource imbalance between an injured worker and their employer is obvious, particularly when the employer is a multi-national corporation with access to legal resources. Self-insurers need to be conscious of these dynamics and ensure workers have access to fair and just processes.

160. Some parties observed that law firms representing self-insurers act in a noticeably more aggressive way than those same firms representing WorkSafe agents or WorkSafe directly. Further, WIC raised concerns that firms providing legal advice sometimes provided different advice depending on whether the claim was managed by a self-insurer or a WorkSafe agent, and questioned whether this was because self-insurer decisions had less oversight by WorkSafe.

161. The self-insurer’s agent in this case told the investigation claims management issues persisted because the self-insurer had not delegated full decision-making authority to the agent. The agent no longer accepts assignments where its ability to act is limited, to avoid such conflicts.

Following conciliation Directions

162. In very limited circumstances, WIC has the power to direct a self-insurer to make limited weekly payments or limited payment for medical expenses. This can only occur if the conciliator is satisfied that:

- the self-insurer has no arguable case to support the decision in dispute and justify not paying entitlements

- the self-insurer refuses to alter their decision voluntarily.

163. WIC does not issue Directions frequently. They can be appealed to the Magistrates Court. The investigation encountered cases where appeals were unsuccessful, but no formal data is available on appeal outcomes. WIC is not advised if a Direction is overturned. This advice should be obtained and reported on as it would allow assessment of the quality of decision-making by WIC and by self-insurers.

164. Thirty per cent of all Directions issued between 1 January 2018 and 8 June 2022 were to self-insurers. Self-insurers must be open to changing decisions when new evidence is available, or the circumstances warrant a reassessment. This should occur even if it is at the eleventh hour of a conciliation or court case. This demonstrates integrity, accountability and the good administrative decision-making the law requires.

165. The investigation saw cases where self-insurers received advice a decision was unsustainable or received new evidence (including on the day of conciliation) that justified a different decision, yet decisions to reject or terminate were maintained. In some cases, self-insurers were slow to make payments even after WIC directed them to.

166. The failure to comply with a Direction is a breach of the WIRC Act punishable by a $55,000 fine. However, WorkSafe must be aware of the breach for there to be consequences for the self-insurer.

Options when conciliation fails

167. If conciliation fails, injured workers of self-insurers have limited options. One is to withdraw from the process.

168. Another is to seek arbitration. WIC’s relatively new arbitration power allows it to make binding determinations on disputed cases after they have not been resolved by conciliation. This is intended to allow people to resolve claims without having to go to court. Arbitration can only be initiated for injuries that occurred after 1 September 2022. At the end of May 2023, no cases had yet been arbitrated.

169. The final option for workers of self-insurers is to take the matter to court. This option can be stressful and expensive, which is especially challenging for people who are injured and not earning income.

170. Victorian workers who do not work for self-insurers have an extra option available – review by WCIRS. But WCIRS cannot consider cases from self-insurers. Various submissions, including from WIC, raised concerns about this lack of access. WIC said:

… injured workers employed by Self-insurers are further hampered by their inability to escalate decisions for review prior to taking their dispute to court. This clearly disadvantages a worker employed by a Self-insurer and distinguishes them from workers whose employers pay premiums to a WorkSafe Agent …

Workers Compensation Independent Review Service

171. In response to the Ombudsman’s 2019 investigation, WorkSafe established WCIRS in April 2020 to review disputed decisions not resolved at conciliation. WCIRS review officers apply consistent sustainable decision-making criteria to their reviews of claim decisions. They then use WorkSafe’s power in the WIRC Act to give directions to WorkSafe agents to overturn unfair decisions. This part of the Act only applies to WorkSafe agents. No equivalent legislative power exists for self-insurers. Injured workers of self-insurers are therefore currently excluded from access.

Why WCIRS works

172. WorkSafe now has compelling evidence to show the positive impact of WCIRS on decision-making by its agents. A single direction from WCIRS can improve the quality of decision-making for many other claims. WorkSafe agents learn from WCIRS directions and apply the principles to future decisions. This is vital to system improvement. The importance of this within the scheme cannot be understated in WorkSafe’s view. If self-insurers were subject to WCIRS, their decision-making should similarly improve.

173. Over time, if claims managers change to align with WCIRS directions, fewer matters would need to proceed to WCIRS. Figure 5 shows a smaller proportion of WorkSafe agent decisions are being overturned by WCIRS or withdrawn by the WorkSafe agent as the system matures. This is because fewer of the disputed decisions referred to WCIRS need to be changed.

174. The results show in its first months of operation (2019-20), 12 of the 13 disputed decisions referred for review (92 per cent) were overturned by the Review Officer or withdrawn by WorkSafe agents. Many more disputed decisions were referred for review the following year (301) with the proportion overturned or withdrawn still relatively high at 50 per cent. In the 2021-22 financial year, only 38 per cent of decisions referred for review were overturned or withdrawn.

175. This process is an important oversight mechanism for WorkSafe that delivers meaningful and systemic improvement.

176. Self-insurers account for a disproportionate number of disputes at conciliation and Directions issued by WIC. Given this, WCIRS may act as an equally strong (if not stronger) impetus for change in self-insurer practices than already seen among WorkSafe agents.

177. This would require close collaboration between self-insurers and momentum by WorkSafe to drive change and develop best practice.

178. It is also noted that only four WorkSafe agents in Victoria manage claims for about 95 per cent of the work force, making it relatively easy for these agents to apply learning from one wrong decision to many other claims. This may be much harder for the 34 self-insurers, some of whom deal with only a small number of claims.

What self-insurers say

179. While some self-insurers acknowledged the current inequity in access to WCIRS, few directly supported the need for change to close the gap; their responses to the draft report instead calling for more detail on how change could be implemented and operationalised.

180. In its response to the draft report, healthcare company Healius claimed that WCIRS reviews were limited in scope in that they only look at adverse decisions:

There has not been any review of decisions made to accept liability which should have been rejected … quality of decision making goes both ways …

It may well be … that the reduced number of disputes being raised with respect to [WorkSafe] Agents is an outcome of [WorkSafe] Agents accepting claims because this is the most practical solution in the circumstances.

181. Westpac did not support self-insurers being subject to WCIRS, stating the conduct of a few should not be considered reflective of all. Crown maintained only self-insurers who engaged in poor conduct should be subject to WCIRS.

182. BlueScope presented a mixed view. It agreed all injured workers should have the right to access WCIRS, though stated in their experience:

WorkSafe are no better positioned to interpret complex matters than an insurer, and ultimately a matter may need to be determined in a legal forum.

183. In their responses to the draft report Westpac, Wesfarmers, Crown, Hanson and RACV called for more detail about how the power to direct by WorkSafe would be implemented and called for review mechanisms to apply.

184. Agent EML which currently acts for three self-insurers, welcomed the suggestion that WCIRS be extended to include self-insured employers to further ensure fair and equitable outcomes for all injured workers. Wesfarmers was also broadly supportive and advised it saw no reason for the employees under a self-insurance program to be subjected to different rights and processes. It suggested a trial of any new process should be considered to assess the effect on claims experiences and conduct.

185. These varied responses indicate the purpose and current functioning of WCIRS may not be well understood. It is not a punitive measure. Fixing the current inequity of WCIRS access would only have an impact on self-insurers who made unsustainable decisions. There would be no basis to overturn decisions of self-insurers undertaking claims management in line with best practice and the legislation.

WorkSafe oversight

186. One of WorkSafe’s key functions is to oversee self-insurers to ensure they manage claims in accordance with laws designed to protect workers and support their return to work. WorkSafe is responsible for approving and monitoring self-insurers to enforce performance standards and promote good decision-making.

187. WorkSafe is also responsible for ensuring self-insurers comply with the Charter of Rights Act. Denying and terminating genuine claims is unfair. Not only could it result in the employees being financially disadvantaged, it could also lead to a loss of dignity and self-esteem and reputation within the workplace.

188. WorkSafe believes that the principles underlying the Claims Manual align with the Charter of Rights Act, however, we saw no evidence that WorkSafe comments on workers' human rights when reviewing claims decisions. Wesfarmers was the only self-insurer to make specific mention of human rights in its response, telling the investigation the company understands and embraces its obligations under the Charter of Rights Act and that corporate values of integrity, accountability and openness underpin their approach to management of its self-insurance portfolio.

189. WIC noted workers of self-insurers are particularly vulnerable and raised questions about WorkSafe’s oversight:

The shortcomings that these [earlier] reports consistently identified with WorkSafe’s oversight of [its] agents are further compounded in the context of Self-insurers, due to the limits of WorkSafe’s role as regulator.

190. While WorkSafe does not have the same power over self-insurers as it does over WorkSafe agents, it is not powerless. It took steps to improve system oversight following our 2016 and 2019 investigations.

191. WorkSafe made further changes in March 2023 to obtain more timely and comprehensive data about claims and decisions, so it is not intervening months later. WorkSafe is also analysing data to identify issues early so it can work with self-insurers, peak bodies, conciliators and agents to remedy poor practice and improve systems.

192. Despite these initiatives, WorkSafe appears to struggle to effectively regulate self-insurers in some areas, constrained in part by the limits of its legislative powers.

193. This report has already highlighted an instance where WorkSafe has failed to verify or scrutinise implementation of its Quality Decision Audit recommendation to the self-insurer. This may have allowed poor practices to continue. WorkSafe acknowledged that verification of Quality Decision Audit recommendations had not been undertaken consistently.

194. During our investigation, WorkSafe acknowledged that a change of approach was required. WorkSafe implemented a procedure to verify the outcome of all its Quality Decision Audits with self-insurers who have agreed with its recommendations. This new procedure ensures the agreed changes are actioned.

195. Another limitation is WorkSafe’s inability under the WIRC Act to direct a self-insurer to overturn an unsustainable decision. In several of the case studies in this report, self-insurers said they agreed with WorkSafe’s recommendations but then did not follow them. WorkSafe’s position as regulator and subject matter expert did not convince those self-insurers to change their decisions.

196. For WorkSafe to compel a self-insurer to change a decision that is unsustainable, it needs this legal power. WorkSafe has not taken any steps to seek this power. It argued it is just now seeing the impact of the power to direct WorkSafe agents as they change their practices in response to WorkSafe’s directions.

197. WorkSafe told the investigation it would welcome the power to direct self-insurers to overturn an unsustainable decision.

198. The power to review and overturn self-insurers’ decisions is not unprecedented in Australia. In Queensland, for example, the Office of Industrial Relations conducts independent reviews which can confirm, vary or set aside a self-insurer’s decision. These are based only on the application and claim file, and review officers cannot make enquiries or conduct investigations.

Approving self-insurers

Initial approval

199. An employer applying to be a self-insurer must first demonstrate to WorkSafe that it is ‘eligible’ under section 375 of the WIRC Act. This primarily means showing it is capable of meeting its potential claims liabilities.

200. Self-insurers must also demonstrate they are ‘fit and proper’. In addition to the employer’s financial viability, WorkSafe must look at a self-insurer’s:

- safety record

- number of workplace injuries

- cost of associated claims

- capacity to manage claims.

201. When assessing the company’s resources for managing claims, WorkSafe advises prospective self-insurers it expects:

a strong claims management, occupational rehabilitation and return to work history, including compliance with the [WIRC Act], appropriate participation and implementation of agreements in conciliation processes, strong results in worker satisfaction surveys, and minimal substantiated complaints, which have been resolved in a timely manner if they occur.

202. In other jurisdictions, expectations of self-insurers are articulated in a more detailed way. For example, in South Australia approval as a self-insurer is conditional on the self-insurer abiding by a detailed Code of Conduct.

203. Finally, WorkSafe must also have regard to ‘such other matters as the Authority thinks fit’. This provision means WorkSafe can consider any other relevant topic. WorkSafe has used this provision to request details of prosecutions under the WIRC Act and details of an employer’s consultations with their employees and relevant unions about the proposal to become a self-insurer.

204. The names of organisations applying to be self-insurers are posted on WorkSafe’s website, and anybody with relevant information can make a submission to WorkSafe as part of the initial approval process.

205. If approved, the new self-insurer is granted an initial approval period of three years.

206. After this, self-insurers may apply to WorkSafe for reapproval. The standard reapproval term is four years. The reapproval process is WorkSafe’s key mechanism for managing self-insurers’ performance and is designed to be informed by data from its various monitoring systems. Reapproval of self-insurers is discussed more later.

Outsourcing to agents

207. The WIRC Act allows a self-insurer to ‘appoint a person approved by the Authority to act as the self-insurer’s agent’ to carry out the role.

208. In 2023, eight self-insurers have WorkSafe approval to outsource the management of some or all of their claims to agents.

209. In a submission, one of these agents, EML, identified its perception of the benefits of ‘effectively managed self-insurance’ as:

- providing immediate access to care and support

- ensuring continuity of care for workers

- bringing strong workplace knowledge, allowing them to tailor and establish suitable duties to assist with an early and sustainable return to work

- delivering direct feedback on opportunities to change operational processes to improve safety and prevent injuries.

210. EML provided its perspective on the advantages of self-insurers using ‘specialist claims managers’. For example, it suggested specialist claims management brings a higher level of expertise and understanding of regulatory requirements.

211. EML also said it provided independent decision-making, though noted in the past not all self-insurers had delegated them full decision-making power. EML acknowledged this had led to conflicts in decision-making.

212. In response to the draft report EML noted that the current Ombudsman investigation had identified opportunities for improvement. It advised it had made significant improvements to its services to self-insurers following the Ombudsman’s previous WorkSafe investigations. EML told the investigation it had:

observed the positive impact of these changes on our decision making including achieving 100% compliance in the most recent WorkSafe Quality Decision audits undertaken in April and November 2022.

213. In contrast, BlueScope questioned whether self-insurer agents offered superior decision-making to self-insurers, noting the conduct of [WorkSafe] agents had led to a review of claims management practices initially by the Ombudsman and other oversight bodies or regulators. Hanson also recommended caution weighing the perceived benefits of appointing an agent. This report includes case studies highlighting problematic approaches involving both self-insurers and their agents.

214. Ordinarily, WorkSafe can direct its agent to overturn a decision. As noted, WorkSafe cannot do this when the agent is acting on behalf of a self-insurer. Perhaps not surprisingly, several submissions raised concerns that agents can behave differently when acting for self-insurers.

215. EML emphasised separate business units manage self-insurer claims and other workers compensation claims. While such separation may be appropriate for management purposes, it carries a risk that any positive changes may not flow equally across the whole system. If changes are made to one claim because the approach or decision was wrong, they should apply to all subsequent claims, no matter the type.

Monitoring self-insurer performance

216. WorkSafe monitors self-insurers through a combination of audits, feedback and complaints. This framework is designed to ensure self-insurers meet their statutory obligations. It adopts a targeted approach for oversight and intervention in line with the risk profile of individual self-insurers.

217. WorkSafe’s oversight framework includes multiple monitoring mechanisms:

- Claims Management Audits

- the tier system

- Self-insurer Self-audit Program

- Performance Improvement Plans

- regulatory monitoring (including complaints, WIC lodgements, enforcement activity and the comprehensive review of performance in the lead up to reapproval).